The Integrated Motivational Volitional (IMV) model of suicide is a comprehensive theoretical model of suicidal behaviour, initially developed by Professor Rory O’Connor of the Glasgow University Suicide Research Laboratory and published in 2011 in an international handbook of suicide prevention (O’Connor, 2011). The IMV model was recently updated, and a review paper published in September 2018 in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society will describe its current structure and rationale. In this blog we describe the model, how it withstands empirical testing, and its relevance to researchers, clinicians, and people who experience suicidal thoughts.

The philosopher Karl Popper maintained that scientific practice should be characterised by its continual effort to test theories against experience and to revise those theories based on the outcomes of these tests. His falsificationist approach held that when theories are falsified on empirical testing, scientists should respond in one of three ways: by revising the theory, rejecting that theory in favour of an alternative, or maintaining that theory but changing one of its constituent hypotheses. Theories of suicide have their roots in the late nineteenth century, when Durkheim’s social integration hypothesis proposed that suicide is the outcome of an underlying imbalance between social integration and social regulation. Suicide is a complex phenomenon, and any theory that attempts to explain it must endeavour to capture factors featuring in the suicidal pathway for the large majority of groups at risk of suicide. A theory that clearly identifies modifiable risk factors is also of great clinical value, describing to clinicians and to people with suicidal thoughts how such patterns of thinking might arise, and how they might be relieved.

Since the work of Durkheim a number of theorists have described the inter-relationship of biopsychosocial factors in the development of suicidal behaviour. Central to recent models such as Thomas Joiner’s interpersonal theory of suicide (Joiner, 2005) and David Klonsky’s three step model of suicide (Klonsky and May, 2015) is the concept of “ideation to action”; that is, that the formation of suicidal thoughts and the progression of these thoughts to actions are two distinct stages with distinct explanations. They hold that the processes leading to suicidal ideation are not sufficient to trigger suicidal acts, and a distinct process is additionally necessary to overcome the psyche’s natural instinct to self-preservation. This explains why the prevalence of suicidal ideation in a population is much greater than that of suicide attempt (McManus et al, 2016). Both models are pared down to a parsimonious set of core concepts. Joiner’s features only three factors: perceived burdensomeness, thwarted belongingness, and acquired ability for suicide. Klonsky’s features four: pain, hopelessness, connectedness, and capacity for suicide.

Émile Durkheim was one of the early suicide theorists who created a normative theory of suicide, which explained it as a social fact, external to the individual, instead of a result of one’s circumstances.

Methods

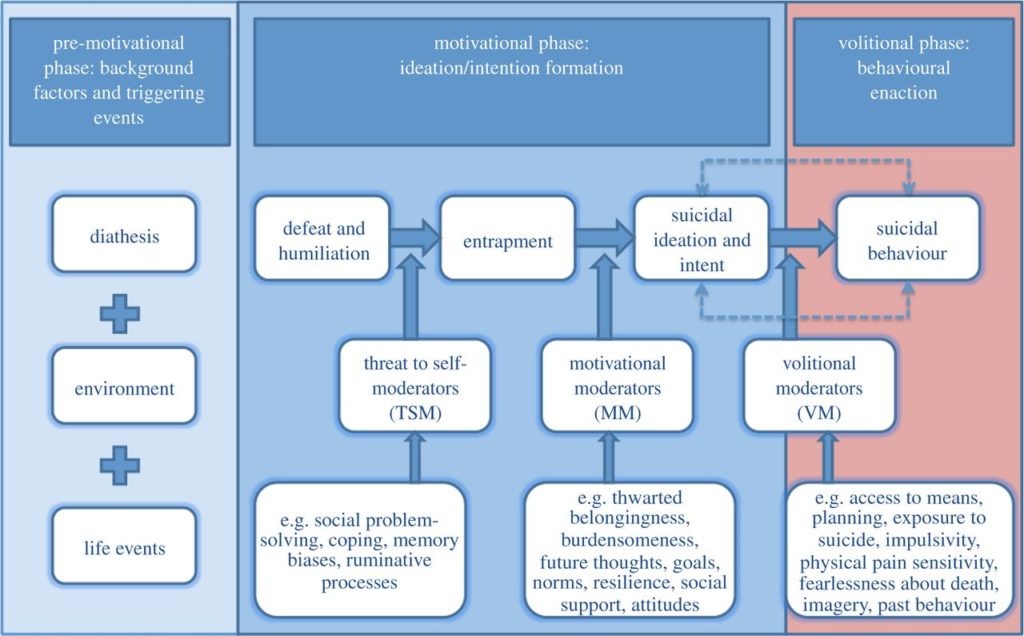

The IMV model belongs to this same generation of ideation to action models (O’Connor and Nock, 2014), but as this 2018 review explains, also draws on four key theoretical perspectives: the diathesis-stress model, the theory of planned behaviour, the cry of pain theory (originating in evolutionary psychology), and the differential action hypothesis. The review carefully explains how these ideas are integrated to describe the emergence of suicidal ideation and the transition to suicidal behaviour in three distinct stages:

- A pre-motivational phase, whereby biopsychosocial vulnerability factors and triggering events (including early life adversity, poverty, and traits such as socially prescribed perfectionism) form the backdrop for the development of suicidal thoughts;

- A motivational phase, which describes how and why suicidal ideation may emerge; and

- A volitional stage, which marks the transition from suicidal thoughts to behaviours.

A key premise of the theory is the idea that defeat and entrapment are the primary drivers of suicidal ideation, and therefore central to the motivational (and middle) stage of this tri-partite model.

Results

The model is clearly explained in this paper, with subsections providing detail on each of the factors featuring in the three phases of the model and their contribution to the ideation-to-action pathway. Although not explicitly identified, the three main changes that have been made to the model since its first iteration in 2011 are as follows:

- Recognition of the cyclical nature of the transition between suicidal thoughts and behaviours, as represented by bidirectional arrows linking the motivational (ideation) and volitional (action) phases

- An expansion of detail on the volitional moderators featuring in the model. Eight are now specified, some of which are well-established (access to means, past suicidal behaviour) and some of which are relatively newly identified (physical pain sensitivity). One has morphed from its 2011 description as ‘imitation (social learning)’, which had implied an over-simplified passive process, to that of ‘exposure to suicide or suicidal behaviour’, broadening this out to consider the impact of a close contact’s suicide or suicide attempt on a person’s internal constraints against self-harm and acknowledging the range of individual meanings that such an exposure might have in shaping behaviour

- Specification of eight premises of the model, identifying key hypotheses to test in relation to predisposing and precipitating factors in the pre-motivational phase, and factors that facilitate or impede transition within or between a phase.

Implications for practice and research

These changes, particularly the inclusion of a cyclical pathway, are improvements. The model’s value to researchers, clinicians, and people who experience suicidal thoughts is as follows:

- It brings together a wealth of suicide research, incorporating into a linear, dynamic and detailed representation the range of social, cultural, environmental, genetic, biological, cognitive, and interpersonal risk factors for suicide. This covers the spectrum from structural environmental factors (such as social inequalities) to interpretive aspects relating to the social meanings of, and opportunities for, suicide among different social groups (including access to means, and responses to another’s suicidal behaviour).

- Clinically it captures the range of histories expressed by those who seek help for suicidality, and particularly the cyclical nature of suicidal ideation and triggering of attempts. This provides clinicians and people with lived experience with a means of understanding an individual’s suicidal thoughts, and how they might try to mitigate them.

- It provides an open invitation for researchers to test hypotheses in specific pathways, addressing the sometimes-expressed critique that suicide research is not sufficiently theory-driven.

- The three sets of moderators are identified as a range of potential therapeutic targets. Should a hypothesis involving any of those moderators be supported, this should prompt the development and trialing of a suitable intervention.

The IMV model provides clinicians and people with lived experience with a means of understanding an individual’s suicidal thoughts, and how they might try to mitigate them.

Strengths and limitations

So does the model stand up to empirical testing?

The review describes which theoretical pathways within the model have been tested, but acknowledges that the majority of those studies were cross-sectional. This is the main drawback, given the biases introduced when conducting mediation analyses using cross-sectional data (Maxwell et al, 2011).

For researchers the model identifies rich opportunities to conduct hypotheses-driven studies of specific pathways, using large, representative longitudinal datasets, with adequate follow-up data, and rigorous methods of causal mediation analysis. Ideally such work should include more studies with non-Western samples, and further research to test the IMV model in relation to self-harm (irrespective of apparent suicidal intent). Longitudinal studies to explore the inter-relationships between defeat, humiliation, entrapment, rumination and suicidal ideation will help make sense of inconsistencies in findings regarding this specific pathway within the motivational phase. Psychodynamic perspectives on the role of humiliation in engendering aggression directed outwards (as violence to others) or inwards (as suicidal behaviour) (Leask, 2013), and qualitative studies exploring lived experiences of suicidal thoughts and behaviours, may also shed light on these complex inter-relationships.

Conclusions

The IMV model is an increasingly influential ideation-to-action model of suicidal behaviour, with a growing evidence base and much promise to inform the development of effective, targeted interventions to prevent suicide. However, there remain some important questions and challenges to be addressed. In line with Popper, researchers’ continual efforts to test and revise the temporal pathways within the model will continue to build this important project, benefitting clinicians and people who suffer the harrowing experience of suicidality.

The IMV model is an increasingly influential ideation-to-action model of suicidal behaviour, with a growing evidence base and much promise to inform the development of effective, targeted interventions to prevent suicide. What would Popper say about it?

Conflicts of interest

Both AP and LM know the authors of the review and have worked with them on other projects. AP is an independent clinical member of Trial Steering Committee for the MQ-funded trial Safetel, for which Prof O’Connor is the PI.

Links

Primary paper

O’Connor RC, Kirtley OJ. (2018) The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behaviour. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 373: 1754 DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2017.0268 http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2017.0268

Other references

Joiner, T.E. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. M. (2015). The Three-Step Theory (3ST): A new theory of suicide rooted in the “ideation-to-action” framework. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 8(2), 114-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2015.8.2.114

Leask P (2013) Losing trust in the world: Humiliation and its consequences, Psychodynamic Practice, 19:2,129-142, DOI: 10.1080/14753634.2013.778485 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14753634.2013.778485

McManus S, Hassiotis A, Jenkins R, Dennis M, Aznar C, Appleby L (2016) Suicidal thoughts, suicide attempts, and self-harm. Chapter 12 in Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey: Survey of mental health and wellbeing in England, 2014. NHS Digital. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/publicationimport/pub21xxx/pub21748/apms-2014-suicide.pdf

Maxwell S.E., Cole D.A, Mitchell M.A (2011) Bias in Cross-Sectional Analyses of Longitudinal Mediation: Partial and Complete Mediation Under an Autoregressive Model, Multivariate Behavioral Research, 46:5, 816-841, DOI: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716

O’Connor R (2011) Towards an Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model of Suicidal Behaviour (p 181-198) in O’Connor R, Platt S & Gordon J (eds). International Handbook of Suicide Prevention: Research, Policy & Practice. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

O’Connor and Nock (2014) The psychology of suicidal behavior. Lancet Psychiatry 1: 73-85

Photo credits

- Photo by Samuel Zeller on Unsplash

- Photo by Neil Thomas on Unsplash

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

[…] Read more: https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/suicide/integrated-motivational-volitional-model-su… […]

[…] is difficult to measure suicide behaviours; but the research tells us that asking people about suicide is safe. Surely, if the aim of a […]