The role of physical illness has received little attention in psychiatric research as a potential marker of suicide risk despite emerging research evidence suggesting that as many as one in ten people who die by suicide were suffering from a chronic illness at the time of their death (Bazalgette, 2011).

Elevated levels of markers of inflammation have also been found in the brains of people who have died by suicide (Pandey, 2012; Steiner, 2008; Tonelli, 2008), suggesting that acute physical illnesses caused by infection might also be associated with an increased risk of suicide.

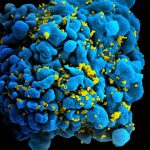

Viral infections that can cross the blood-brain barrier, such as influenza, have been associated with suicidal behaviour (Okusaga, 2011). Rates of suicidal ideation have also been found to be higher in those infected with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) (De Aledida, 2016) and hepatitis C (Lucaciu, 2015).

These studies have tended to rely on cross-sectional research designs, thereby precluding clarification of whether infection lies on the causative pathway towards suicide, or alternatively, whether it is merely coincidence that patients who engage in suicidal behaviour also have brain markers suggestive of infection and inflammation (Black, 2015; Brundin, 2016). For these reasons, longitudinal population-based research, in which people are followed prospectively over time, is required to help understand the role of infection in suicide.

Emerging research suggests that infection may be associated with an increased risk of suicide. But could infections cause suicidal behaviour?

Methods

A cohort study of all Danish citizens, aged 15 years and older at January 1, 1980, was therefore undertaken to investigate the prospective risk of suicide associated with the number of hospitalisations a person had for different types of infection over a maximum follow-up period of 32 years.

Results

The cohort consisted of 7,221,578 Danish citizens:

- Males: 3,601,653 (49.9%)

- Females: 3,619,925 (50.1%)

Over the course of the 32 year follow-up period around one in ten (809,384; 11.2%) persons were hospitalised with an infection on at least one occasion and 32,683 (0.5%) died by suicide.

- Almost one-quarter of those who died by suicide had been hospitalised at least once for an infection over the 31 year follow-up period (7,892; 24.1%):

- Incidence Rate Ratio – adjusted for sex, age, calendar period (IRR): 1.61, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.56 to 1.65.

The risk of suicide varied by infection type, with the highest risk for those hospitalised for HIV or Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS):

- HIV or AIDS: IRR 6.33, 95% CI 5.09 to 7.88

- Hepatitis: IRR 3.61, 95% CI 3.17 to 4.11

- Sepsis: IRR 2.17, 95% CI 1.91 to 2.45

- Respiratory tract: IRR 1.86, 95% CI 1.79 to 1.94

- Skin: IRR 1.68, 95% CI 1.60 to 1.76

- Urological: IRR 1.65, 95% CI 1.55 to 1.76

- Genital: IRR 1.53, 95% CI 1.42 to 1.65

- Central nervous system: IRR 1.42, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.65

- Gastrointestinal tract: IRR 1.21, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.27

- Otitis media: IRR 1.11, 1.00 to 1.23.

Pregnancy-related infections were not associated with an increased risk of suicide: IRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.13.

The risk of suicide also appeared to vary by pathogen type, with risk slightly higher for ‘other’ pathogens (including parasites, prions, etc.) infections:

- Other pathogens (e.g., parasites, prions): IRR 1.68, 95% CI 1.59 to 1.77

- Bacterial: IRR 1.57, 95% CI 1.52 to 1.62

- Viral: IRR 1.45, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.54.

The risk of suicide also appeared to increase in a linear fashion as the number of hospitalisations for different infections each person had increased:

- 7 or more infections: IRR 2.90, 95% CI 2.14 to 3.93

- 1 infection: IRR 1.34, 95% CI 1.30 to 1.38.

Finally, given that diagnosis with a major psychiatric disorder is a significant risk factor for suicide, the authors conducted a sub-group analysis excluding those persons who had ever been diagnosed with any major psychiatric disorder. They found that those who had never been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder but who had been hospitalised for an infection were, nevertheless, significantly more likely to die by suicide as compared to those who had never been hospitalised for an infection: IRR 1.31, 95% CI 1.27 to 1.36.

The authors further stratified their sample by the timing of diagnosis with any major psychiatric disorder, finding that those whose diagnosis pre-dated their hospitalisation for infection were at significantly increased risk of suicide compared to those whose diagnosis occurred after their hospitalisation for infection:

- Those with a diagnosis of any major psychiatric disorder that pre-dated their hospitalisation for infection: IRR 1.27, 95% CI 1.21 to 1.34

- Those with a diagnosis of any major psychiatric disorder post-dating their hospitalisation for infection: IRR 1.04, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.09.

These results suggest that infections may play a part in the pathophysiological mechanisms of suicidal behaviour.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that being hospitalised for an infection at least once is associated with a 42% increased risk of death by suicide.

The authors also found that having an infection remained significantly associated with an increased risk of suicide even in those without a diagnosis for a major psychiatric disorder, suggesting that the association between infection and suicide cannot be solely explained by psychiatric history.

Strengths and limitations

This paper addresses an important gap in the research literature by making use of a longitudinal, population-based sample to prospectively investigate the association between infection and suicide in the community over a long follow-up period (32 years).

Denmark, like many Scandinavian countries, has an established method of linking together nationwide registries using unique, personal identification numbers. All persons living in Denmark, including migrants and temporary residents, are assigned a unique personal identification number. This number can then be used to identify persons in the various databases held by the Danish Civil Registration System, including the Danish National Hospital Register, the Psychiatric Central Research Register, and the Cause of Death Register.

Exposure status in this study were identified from an episode of infection treated in hospital-based settings for the first half of the follow-up period (1980 to 1995). Consequently, persons with milder infections not necessitating hospital treatment would not have been included. Those treated in either hospital or outpatient services were, however, included from 1995 until the end of the observation period. Nevertheless, those with undiagnosed infections would still not have been included in the study. Residual confounding therefore cannot be ruled out.

Second, the authors were unable to adjust their risk estimates for history of previous self-harm or suicidal behaviour as these behaviours are currently not captured in the Danish hospital data registries. Given that previous self-harm is amongst the strongest risk factor for suicide (Zahl, 2004), this may reduce the association between infection and suicide to non-significance. Future research should therefore adjust for prior non-fatal suicidal behaviour in addition to sex, age, and other relevant confounders.

Lastly, residents of Greenland and the Faroe Islands are not included in the Danish Civil Registration System (Schmidt, 2015). However, although the incidence of suicidal behaviour in the Faroe Islands is low (Wang AG, 2006), suicide rates are higher in Greenland as compared to Denmark (Bjerregaard, 2015). The exclusion of Greenlanders from the present study may therefore have introduced bias.

Summary

This study demonstrates an increased risk of death by suicide among individuals hospitalised at least once for an infection. The authors estimate that as many as 1 in 10 suicides could be prevented if interventions could be developed to eliminate all infections from the community.

If you need help

If you need help and support now and you live in the UK or the Republic of Ireland, please call the Samaritans on 116 123.

If you live elsewhere, we recommend finding a local Crisis Centre on the IASP website.

We also highly recommend that you visit the Connecting with People: Staying Safe resource.

Links

Primary paper

Lund-Sørensen H, Benros ME, Madsen T, Sørensen HJ, Eaton WW, Postolache TT, Nordentoft M, Erlangsen A. (2016). A nationwide cohort study of the association between hospitalization with infection and risk of death by suicide. JAMA Psychiatry, 73: 912-19. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1594.

Other references

Bazalgette L, Bradley W, Ousbey J. (2011). The Truth about Suicide. London: Demos. ISBN: 978-1-906693-77-0. Accessed 25 November, 2016 from: https://www.demos.co.uk/files/Suicide_-_web.pdf.

Black C, Millner BJ. (2015). Meta-analysis of cytokines and chemokines in suicidality: Distinguishing suicidal versus nonsuicidal patients. Biological Psychiatry, 78: 28-37. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.10.014.

Brundin L, Bryleva EY, Rajamani KT. (2016). Role of inflammation in suicide: From mechanisms to treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews. DOI: 10.1038/npp.2016.116.

De Almeida SM, Barbosa FJ, Kamat R, et al. (2016). Suicide risk and prevalence of major depressive disorder (MDD) among individuals infected with HIV-1 subtype C versus B in Southern Brazil. Journal of Neuroviology. DOI: 10.1007/s13365-016-0454-3.

Lucaciu LA, Dumitrascu DL. (2015). Depression and suicide ideation in chronic hepatitis C patients untreated and treated with interferon: Prevalence, prevention, and treatment. Annals of Gastroenterology, 28: 440-47. [PMC4585389].

Okusaga O, Yolken RH, Langenberg P, et al. (2011). Association with seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. Journal of Affective Disorders, 130: 220-5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.029.

Pandey GN, Rizavi HS, Ren X, et al. (2012). Proinflammatory cytokines in the prefrontal cortex of teenage suicide victims. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 46: 57-63. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.08.006.

Schmidt M, Johannesdottir-Schmidt S, Sandegaard JL, et al. (2015). The Danish National Patient Registry: A review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clinical Epidemiology, 7: 440-90. DOI: 10.2147/CLEP.S91125.

Steiner J, Bielau H, Brisch R, et al. (2008). Immunological aspects in the neurobiology of suicide: Elevated microglial density in schizophrenia and depression is associated with suicide. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 42: 151-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.013.

Tonelli LH, Stiller J, Rujescu D, et al. (2008). Elevated cytokine expression in the orbitofrontal cortex of victims of suicide. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavia, 117: 198-2006. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01128.x.

Wang AG, Mortensen G. (2006). Core features of repeated suicidal behaviour: A long-term follow-up after suicide attempts in a low-suicide-incidence population. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41: 103-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00127-005-0980-4.

Zahl D, Hawton K. (2004). Repetition of deliberate self-harm and subsequent suicide risk: Long-term follow-up study of 11 583 patients. British Journal of Psychiatry, 185: 70-5. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.185.1.70.

Photo credits

- By NIAID (HIV-infected T cell) [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

- Anthony Easton CC BY 2.0

- 143d ESC CC BY 2.0

- CC BY 2.0

@Mental_Elf ? no way

Today @qu1t1 on Danish cohort study of assoc btwn hospitalisation with #infection & risk of death by #suicide https://t.co/hSnDe6OftH

Recent @JAMAPsych study suggests infections may play a part in pathophysiological mechanisms of suicidal behaviour https://t.co/hSnDe6OftH

@Mental_Elf ‘eliminating all infections from the community’ is quite an optimistic recommendation!!

Infection with #hepatitis, #HIV or #AIDS may be significant risk factor for #suicide https://t.co/DjULSJjwMo @Mental_Elf on a #cohortstudy

#WorldAIDSDay

Important research:

Infection with hepatitis, HIV or AIDS may be significant risk factor for suicide… https://t.co/OqKOhnuz3w