People with mental illness have a significantly shorter life expectancy than the general population. Estimates are as high as 20 years of life lost prematurely in conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (World Health Organisation, 2018). Suicide and physical health comorbidities are the leading causes of premature mortality in this population. Urgent action is needed to tackle this shocking inequality.

In recent decades, efforts to improve general population life expectancy have had success – but such efforts have not reduced disparities for those experiencing mental illness and, in fact, evidence suggests the problem is worsening (Hayes et al., 2017).

In this article (published yesterday in The Lancet Psychiatry), Rory O’Connor and colleagues (2023) put forward the “Gone Too Soon” framework – which identifies ‘priorities for action to prevent premature mortality associated with mental illness and mental distress’. The Framework’s purpose is to:

mobilise the translation of evidence into prioritised actions to reduce premature mortality by identifying key causes, gaps in knowledge, and existing or promising solutions.

Previous efforts typically conceptualised premature mortality due to suicide and physical health comorbidities as separate issues or domains, here, however, O’Connor and colleagues uniquely combine both under one framework with the potential to reduce disparities relevant to both.

Suicide and physical health comorbidities are leading causes of premature mortality in people with mental illness.

Methods

The charity, MQ Mental Health Research, convened 40 international experts including people with lived/living experience, and clinicians, researchers, and policymakers from broad disciplines.

A committee of experts generated a worksheet to gather information on potentially important contributing factors and solutions. The worksheet was then completed by each expert and results analysed to identify themes to guide discussion in a series of online workshops for each domain (suicide and physical health comorbidity).

In the first workshop, members reviewed and ranked the potentially important factors and solutions. Top-ranking items were then further ranked by the committee, focusing on impact (depth/breadth) and feasibility (viability, funding interest and availability) to generate overall ratings.

In a second workshop, further refinements were made, supplemented by literature searching. Solutions, relevant to both domains, were identified during the analysis.

Results

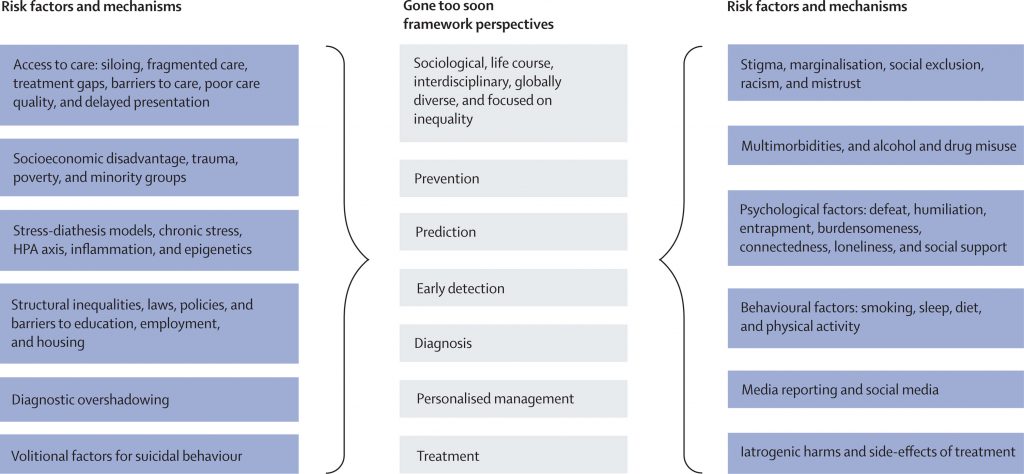

Twelve key risk factors and mechanisms were identified across themes that were found to significantly overlap in association with premature mortality due to both suicide and physical health comorbidities.

Multifactorial nature of risk

It is recognised that risk is not due to a single factor, but instead a combination of interactions between biological and social or environmental factors such as poverty or marginalisation that may lead to feelings of worthlessness or social dis-connection that impact stress experienced by an individual.

Social determinants, structural inequalities, and social context

The authors acknowledge that there are major gaps in understanding the context and events that occur in the time between experiencing structural inequality, such as unemployment, lack of social network, or homelessness, that may result in premature mortality. It is known that people with mental illness are more at risk of inequalities and disadvantaged by a lack of social support and access to services. It was highlighted that people from racialised communities are more at risk of social isolation and thus, premature mortality.

Volitional factors are described as having access to methods of suicide and exposure to others’ suicide, however, research needs to address the move from ideation to attempt or acts. This is also linked to how social media and media channels frame suicide.

Stigma, marginalisation, racism, and mistrust

In some countries, suicide is illegal and criminalised and, thus, even more highly stigmatised. The review notes that this is counterproductive and limits accessibility of services and help-seeking by individuals at risk of premature mortality. They recognise that healthcare approaches to suicide need to include the effects of social and political attitudes and how premature mortality is predicated by social inequality. It is also highlighted that sexual, gender and ethnic minorities amongst other minoritised groups are more vulnerable to suicide risk and the role of racism and colonialism should not be discredited especially in the context of help-seeking in healthcare and the stigmatisation of mental health more widely and should be prioritised in research.

Individual factors

Experiences such as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), behavioural habits and early life experiences are identified as impacting on suicide risk. However, the mechanisms behind them are wide-ranging from biological to social, which all need further exploration. Increased physical health problems, for example, cardiovascular illness linked to behavioural habits such as smoking, diet and sleep should be considered equally too. An interesting factor highlighted in this area is religion which has varying impacts depending on having minoritised characteristics (i.e., LGBTQ+ status).

Personal health influenced by environmental exposure and the gut microbiome is an area identified as receiving rightfully increased research focus through the association of the gut-brain axis with the risk of physical comorbidities. Genetic factors and influences were also found to be potential risk factors and subject to research exploration.

Multimorbidities and alcohol and drug misuse

The review highlights that having multiple illnesses and misuse of substances are widely known to increase the risk of premature mortality, particularly in severe mental illnesses, and other stigmatised illnesses, such as HIV, which may be more prevalent in developing nations. The greater the number of illnesses, the greater the risk of premature mortality, and it is highlighted that some prescription medications may increase the risk of secondary illnesses by protecting against premature mortality from the primary illness. This is also influenced by unequal access to medications from country-to-country, which then impacts health outcomes.

A range of mental illnesses have been associated with suicide risk and the authors note that some illnesses such as PTSD are more significant for suicide attempts than ideation which requires research to focus separately on attempt and ideation.

Access to care: silos, fragmentation, gaps, and quality

The authors recognise the problematic nature of separating physical and mental health care. Physical health symptoms are often ignored in mental health patients and vice versa, and there is also an historic underfunding or lack of funding for mental health services in some countries. The translation of psychiatric practice from the global North to the global South may further worsen health outcomes by failing to recognise the spiritual and religious aspects of healing as well as the local context of health. It is also noted that rurality and barriers to access are linked to increased mortality which means that populations are receiving differing qualities of care. However, they highlight that even where healthcare is free and accessible, improvement in outcomes is not significant, therefore sufficient resource and research is essential to advance intervention, prevention and improve outcomes.

The Gone Too Soon framework and the shared social-ecological risk factors and mechanisms to tackle inequality. (Figure 2, O’Connor et al, 2023). [Click to view larger figure]

‘Actionable solutions’

As a result of the identified risk factors, the authors propose actionable solutions with examples that could be implemented.

Integration of mental and physical health care

This consists of bringing physical and mental health care together and having collaborative care for people with multiple conditions. Improving the training of healthcare staff and building capacity within healthcare is important to efficiently treat mental and physical health problems together. This will also improve access and the authors particularly suggest improvement in access to primary care services. Routine screening, early identification and treatment will normalise and allow for the effective detection of comorbidities.

Prioritisation of prevention while strengthening treatment

A multi-disciplinary approach by preventing access to means of suicide and decriminalisation of suicide in countries where it is illegal. This can also be through tackling stigma through social media and engagement with the public. Preventing secondary illnesses (e.g., from smoking) through interventions that address behavioural habits, as well as guidance in the workplace to promote healthy workplaces. Public health awareness and education about community interventions are listed as prevention techniques whilst improving access to effective treatments will address both prevention and treatment.

Optimising interventions across social and environmental levels

This addresses the multi-level factors that are linked to premature mortality. Optimising interventions through addressing individual- to structural-level issues will allow for better interventions and implementation. Addressing income inequality, reducing stigma and discrimination and increasing investment in mental health will enable equitable access for more people. Using digital opportunities and big data to improve mental health interventions is highlighted as an example to achieve optimisation, as well as a better understanding of the interactions between biological and psychosocial risk factors.

The authors highlight the need to prioritise prevention over intervention and optimise multi-level interventions to address health inequalities.

Conclusions

The authors highlight that placing living and lived experiences at the centre of implementation will optimise uptake and interventions that are best suited to people. Collaboration and involvement are required at public health, governmental, and community level so that implementation is influenced by all relevant stakeholders and is pivotal to driving improvement in this area.

The authors conclude that there are multiple reasons to address premature mortality and suicide in people with mental illness including the economic advantage of a healthy population. Ensuring equal human rights and legislation that protects those living with or at risk of mental health problems will go some way to equitable care for at-risk groups and presenting actionable solutions that can be implemented globally will help prevent premature mortality and those affected by suicide.

Collaboration and co-production with experts by experience are pivotal to addressing premature mortality in people with mental illness.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this paper is the collaborative interdisciplinary input from a wide range of stakeholders including living and lived experience advisors. This enabled a multi-perspective approach covering significant research from the biological, social and psychological sciences linked to both suicide and physical health comorbidities at multiple socio-ecological levels. A wide range of research from developing countries such as research in South Africa, India, and Uganda is mentioned in the review. They also acknowledge the differences in culture, healthcare and access for people in low- and middle-incomes countries in the review.

The majority of the 40 experts were from high-income countries, and specialists in mental health, and the whole process was conducted in the English language. A more extensive inclusion of a greater number of voices, individuals representing other disciplines, and wider public consultation may have yielded important different insights and priorities.

A further strength was the conceptualisation of “mental distress” in addition to “mental illness”, recognising that suicide in particular affects people along a continuum of mental distress, not just those with diagnosed conditions.

A key priority for the authors was global inclusion and diversity. Resource allocation for subsequent implementation efforts will need to be equitable in order to not exacerbate already existing disparities, and solutions will need to be tailored to the local contexts to ensure feasibility and acceptability.

“Funding interest” was including as an indicator of feasibility when ranking potential solutions. Whilst this is pragmatic, it highlights that funding priorities may not always align with the priorities of affected communities – which could perpetuate some inequalities. It would have been interesting to see what the results would have looked like without the consideration of funding.

Whilst this framework has gone some way in highlighting risk factors and actionable solutions to tackle premature mortality, and is a big step forward, it is clear that there is still some way to go to achieve implementation and improved outcomes for people with mental illness and distress.

The inclusion of more consultants from low- and middle-income settings may have allowed different priorities to emerge.

Implications for practice

Although efforts from within mental health contexts are fundamental, it is also essential that a collaborative interdisciplinary approach is taken to address the “multifactorial nature of risk” for premature mortality due to suicide and physical health comorbidities.

Accordingly, efforts to address premature mortality require a multi-systems approach. Governments, funders, and policymakers need to acknowledge this as a priority area and dedicate sufficient funding.

Different countries will need to take into account their own local culture and socio-economic factors when implementing solutions identified in this framework.

As PhD students, it is encouraging to see the collaborative approach taken in this review – which highlights the strength of engaging multiple stakeholders, including lived and living experience, to tackle public health challenges such as this and provides a great example for the proposed implementation of a similar approach.

Implementing this framework will require countries to consider their socioeconomic state and local culture.

Statement of interests

Alvin Richards-Belle is a PhD student in the UCL Division of Psychiatry supervised by a co-author of the article, but this blog was written independently.

Humma Andleeb is also a PhD student at UCL however there are no conflicts of interest noted.

Links

Primary paper

O’Connor, R., Worthman, C. M., Abanga, M., Athanassopoulou, N., Boyce, N., Chan F. L., et al. (2023) Gone Too Soon: priorities for action to prevent premature mortality associated with mental illness and mental distress. The Lancet Psychiatry. Published: May 11, 2023 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00058-5

Other references

World Health Organisation. (2018). Management of physical health conditions in adults with severe mental disorders: WHO guidelines. World Health Organization.

Hayes, J. F., Marston, L., Walters, K., King, M. B., & Osborn, D. P. J. (2017). Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000–2014. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 211(3), 175–181.

Photo credits

- Photo by engin akyurt on Unsplash