In 2021, 1.3% of deaths in the United States and 1.1% in the UK were due to suicide (World Health Organization, 2019). Among adolescents in the UK, the number of suicides increased by 8% compared to 2010 (Liu et al., 2022).

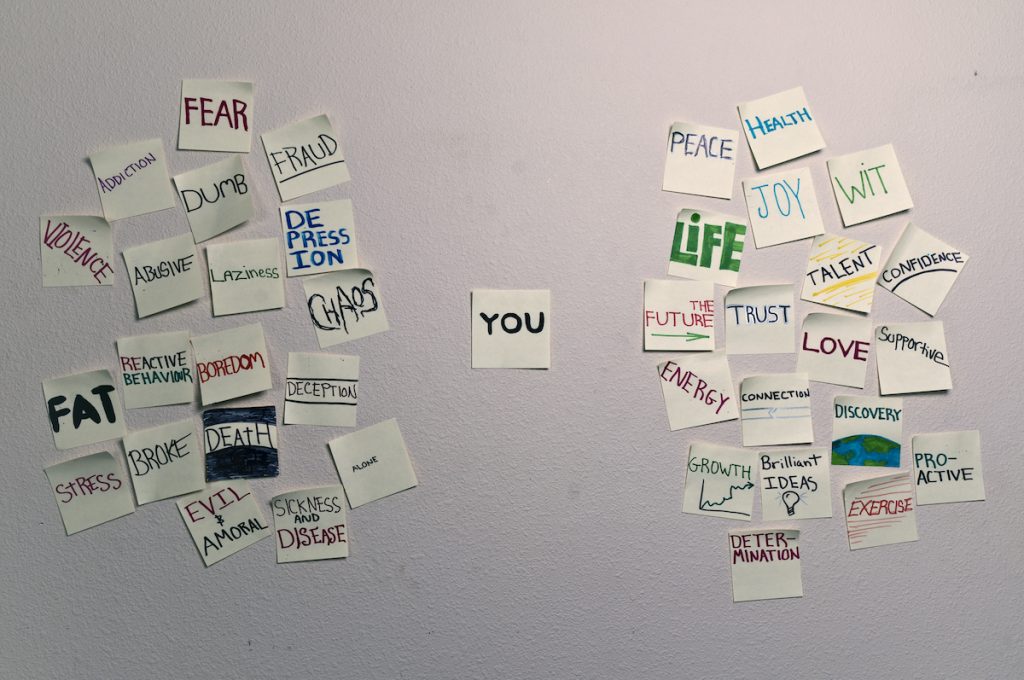

Suicide is widely considered to be a complex phenomenon influenced by a variety of factors. Mental health difficulties (e.g., depression, anxiety, and eating disorders), a family history of suicidal attempts, stressful life events, and living in a disadvantaged environment have all been recognised as psychosocial risk factors for early-life suicide (Bilsen, 2018).

Recently, genetic studies suggested that suicide can also be heritable and influenced by a combination of multiple genetic variants (Coon et al., 2020; Ruderfer et al., 2020), implying that suicide risk could be a polygenic trait just like other mental illnesses. Moreover, genes associated with increased suicide risk are distinct from those associated with depression or other mental illnesses that can lead to suicidal attempts (Erlangsen et al., 2020; Levey et al., 2019; Strawbridge et al., 2019). Based on previous findings, individuals’ polygenic risk score (PRS) for adult suicide, i.e., their additive genetic risk of suicidal behaviour, can be estimated and potentially inform suicide prevention policies.

To further validate the genetic predisposition for suicide, this study aims to examine the associations between children’s PRSs for suicide and their suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Lee et al, 2022c).

Suicide among adolescents in the UK increased by 8% since 2010. Could genetic factors affect childhood suicide?

Methods

The study utilised data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, a long-term project tracking the biological and behavioural development of 11,880 children in the US from ages 9-10 into young adulthood. The authors analysed data at baseline and 2-years follow-up. Children were identified as having suicidal thoughts or attempts based on self-report and informant-based reports, while demographic, socioeconomic, clinical and family history information was gathered from the ABCD survey.

To quantify each child’s genetic susceptibility to suicide, researchers calculated polygenic risk scores (PRSs), which represent an individual’s overall genetic risk based on the total number of genetic variants related to suicide. Multivariate logistic regression was used to analyse whether genetic risk factors were associated with an increased likelihood of suicidal thoughts and attempts. The study also investigated if this association was dependent on or modified by other risk factors for suicide, such as mental health, personality, and socioeconomic status.

Results

The study analysed 4,344 participants from the ABCD study to investigate the association between children’s genetic risk for suicide and suicidal thoughts and behaviours (STBs). The participants had a mean age of 9.63 years at the start of the study, with 2,045 (47%) of them being female. The genetic risk for suicide in children followed a normal distribution and was not associated with any demographic or technical variables.

How common are suicidal thoughts and attempts in young children?

The study found that the number of children attempting suicide tripled, and the number of children having suicidal thoughts doubled within the two-year follow-up. In contrast to children without STBs, children who experienced STBs had a higher prevalence of certain characteristics. These risk factors included low socioeconomic status, parental history of suicide or mental health difficulties, and childhood mental health conditions such as depression. The same tendencies were also found in the follow-up observations.

Does having genes that increase the risk of suicide increase the chances of attempting suicide in childhood?

Children who have genes that make them more susceptible to suicide (i.e., higher PRSs) were more likely to attempt suicide. As more children attempt suicide each year, the link between genetic risk and suicide attempts becomes stronger. Statistically, a one-unit increase in genetic risk for suicide from the norm results in a 39% to 43% increase in the likelihood of children attempting suicide. However, having those genes does not increase suicidal thoughts. No differences were found between children with high genetic risk and those without.

Could this association be explained by children’s genetic risk for other mental health conditions?

Children with a higher genetic risk of major depressive disorder (MDD) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) are more prone to suicide. Nonetheless, even after accounting for the genetic influences of MDD and ADHD, the association between the genetic risk of suicide and youth suicidal attempts remains. This suggests that the genetic risk for suicide is partially independent of the genetic risk for mental illnesses.

Do other psychosocial factors play a role in how genetic risk factors contribute to suicidal behaviours?

Children with a genetic predisposition to suicide may be more likely to attempt it if they have mood-related difficulties, maladaptive behaviours, or certain temperaments. Those may refer to a range of mental health problems and behaviours that can cause distress and impairment in daily life. Furthermore, children’s socioeconomic origins, particularly single-parent status and a lack of parental college degrees are strongly linked to suicidal attempts. However, while youth suicide is related to many other factors, genetic risk for suicide is a reliable predictor of childhood suicidal attempts.

This research suggests that pre-identified genetic risk factors for suicide increase the likelihood of suicidal attempts, independently of comorbidities such as ADHD or major depression.

Conclusions

The authors highlight the genetic basis of suicide and report a significant association between genetic risk for suicide and childhood suicidal attempts, independent of the genetic influences of other mental health difficulties, such as major depressive disorder, and the presence of other psychosocial risk factors. This new evidence could facilitate the identification of children at higher risk of attempting suicide sooner and, thus, inform country-wide prevention strategies and targeted interventions.

New evidence on the genetic basis of suicide could facilitate the identification of children at higher risk of suicide and lead to early intervention. But how can this be done in practice?

Strengths and limitations

Recent advances in genetic techniques have enabled researchers to conduct studies and explore the links between genes and suicidality. This study, particularly focusing on children is crucial to identify research priorities and a framework for suicide prevention among children and adolescents. Utilising secondary data from the comprehensive ABCD study provides cost-effective, easy-to-conduct research while optimising the output of previous research. Moreover, the study considers variables that can strengthen the link between genetics and suicidal thoughts and behaviors, reflecting the complexity of how these factors interact.

However, there are several limitations to the study. Firstly, the study population was based in the United States, potentially limiting the generalisability of the findings to other cultural or geographical contexts. Additionally, the polygenic risk scores (PRS) for suicide were derived from genetic studies of European adults, which may also limit the generalisability to other ethnic groups.

Secondly, while the study shows that suicide risk could be influenced by genetic factors, it is essential to note that genetic risk scores are not deterministic and should be interpreted alongside other factors, such as environmental influences. The small effect size, though statistically significant, also suggests a relatively weak magnitude, which may limit the clinical significance and practical implications of the findings. Furthermore, since PRS is derived by aggregating the effects of single genetic variants, the use of PRSs might not capture the full complexity of genetic influences on suicidal attempts, as they fail to account for gene-gene or gene-environment interactions.

This is a novel study exploring the complexity of the genetic, environmental and personal factors that determine suicidality in children.

Implications for practice

Discovering the genetic basis of suicidal thoughts and behaviours opens the possibility of developing interventions to reduce the risk of suicide in high-risk children. While routine genetic screening is not yet standard practice, it is important to monitor and support children considered ‘high-risk’ due to their mental health problems, living context, adverse experiences, or a family history of suicide. The practical and ethical issues surrounding genetic testing in children and adolescents must be considered before implementing routine screening for suicide genetic risks.

Given that suicide is a complex phenomenon with multiple contributing factors, our understanding of the role genetics plays in this complexity is still limited. Moreover, it is also hard for the public to believe that suicide could be heritable (Kious et al., 2021). Notably, knowing that themselves or their loved ones “carries genes related to suicide” could increase their distress. Therefore, as genetic testing for other diseases, genetic screening for suicide should be accompanied by genetic counselling to address potential concerns.

Could these findings inform the implementation of genetic screening and interventions for children who are at a ‘high risk’ of suicide?

Statement of interests

None to declare.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog from Bass student group: Bella Branch, Charlotte Yunzhi He, Chih-Hsin Huang, Constance Howard, Craig Manavele, Danyang Liao, Eva Brvar, Farisa Dar, Mahnoor Rafiq, Mariya Taneska (@marijataneska1), Yufei Jin and Ziyi Zhao.

UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a group of students on the Clinical Mental Health Sciences MSc at University College London. A full list of blogs by UCL MSc students can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Lee, P. H., Doyle, A. E., Silberstein, M., Jung, J., Liu, R. T., Perlis, R. H., Roffman, J. L., Smoller, J. W., Fava, M., & Kessler, R. C. (2022c). Associations Between Genetic Risk for Adult Suicide Attempt and Suicidal Behaviors in Young Children in the US. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(10), 971.

Other references

Bilsen, J. (2018). Suicide and Youth: Risk Factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9.

Coon, H., Darlington, T. M., DiBlasi, E., Callor, W. B., Ferris, E., Fraser, A., Yu, Z., William, N., Das, S. C., Crowell, S. E., Chen, D., Anderson, J. S., Klein, M., Jerominski, L., Cannon, D., Shabalin, A., Docherty, A., Williams, M., Smith, K. R., … Gray, D. (2020). Genome-wide significant regions in 43 Utah high-risk families implicate multiple genes involved in risk for completed suicide. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(11), Article 11.

Erlangsen, A., Appadurai, V., Wang, Y., Turecki, G., Mors, O., Werge, T., Mortensen, P. B., Starnawska, A., Børglum, A. D., Schork, A. J., Nudel, R., Bækvad-Hansen, M., Bybjerg-Grauholm, J., Hougaard, D. M., Thompson, W. K., Nordentoft, M., & Agerbo, E. (2020). Genetics of suicide attempts in individuals with and without mental disorders: a population-based genome-wide association study. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(10), 2410–2421.

Kious, B. M., Docherty, A. R., Botkin, J. R., Brown, T. R., Francis, L. P., Gray, D. D., Keeshin, B. R., Stark, L. A., Witte, B., & Coon, H. (2021). Ethical and public health implications of genetic testing for suicide risk: Family and survivor perspectives. Genetics in Medicine : Official Journal of the American College of Medical Genetics, 23(2), 289–297.

Lee, P. H., Doyle, A. E., Li, X., Silberstein, M., Jung, J., Gollub, R. L., Nierenberg, A. A., Liu, R. T., Kessler, R. C., Perlis, R. H., & Fava, M. (2021). Genetic Association of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Major Depression With Suicidal Ideation and Attempts in Children: The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study. Biological Psychiatry, 92(3), 236–245.

Liu, R. T., Walsh, R. F. L., Sheehan, A. E., Cheek, S. M., & Sanzari, C. M. (2022). Prevalence and Correlates of Suicide and Nonsuicidal Self-injury in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(7), 718–726.

Levey, D. F., Polimanti, R., Cheng, Z., Zhou, H., Nunez, Y. Z., Jain, S., He, F., Sun, X., Ursano, R. J., Kessler, R. C., Smoller, J. W., Stein, M. B., Kranzler, H. R., & Gelernter, J. (2019). Genetic associations with suicide attempt severity and genetic overlap with major depression. Translational Psychiatry, 9(1).

Ruderfer, D. M., Walsh, C. G., Aguirre, M. W., Tanigawa, Y., Ribeiro, J. D., Franklin, J. C., & Rivas, M. A. (2020). Significant shared heritability underlies suicide attempt and clinically predicted probability of attempting suicide. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(10), Article 10.

Strawbridge, R. J., Ward, J., Ferguson, A., Graham, N., Shaw, R. J., Cullen, B., Pearsall, R., Lyall, L. M., Johnston, K. J. A., Niedzwiedz, C. L., Pell, J. P., Mackay, D., Martin, J. L., Lyall, D. M., Bailey, M. E. S., & Smith, D. J. (2019). Identification of novel genome-wide associations for suicidality in UK Biobank, genetic correlation with psychiatric disorders and polygenic association with completed suicide. EBioMedicine, 41, 517–525.

World Health Organization. (2022). Cause-specific mortality, 2000-2019.