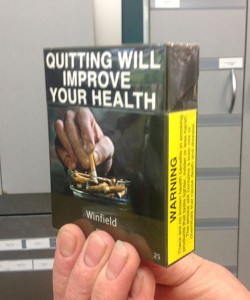

Standardised (or ‘plain’) packaging of cigarettes requires all branding to be removed, leaving the brand name to be placed in a standard location and font on a standard colour cigarette pack. Apart from the small brand name, the packs would still feature a prominent health warning as well as counterfeiting marks.

The aim of standardised packaging is to prevent uptake of smoking, particularly among young people and encourage smoking cessation among current smokers. Australia became the first country in the world to introduce standardised packaging, in December 2012.

The UK government are considering introducing standardised packaging, and in 2012 ran a lengthy public consultation on the issue. A systematic review of the evidence for standardised packaging, commissioned by the Department of Health, and conducted by researchers who are part of the Public Health Research Consortium, was submitted to this consultation (Moodie et al, 2012). This review concluded that there was ‘strong evidence’ to support standardised packaging.

However, the story is not that simple, and the four major transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) (British American Tobacco, Imperial Tobacco, Japan Tobacco International and Philip Morris), who strongly oppose standardised packaging legislation also submitted reviews of the evidence to the consultation. Totalling 1,521 pages overall, these responses were just four of the 2,444 detailed responses submitted to the consultation. The Department of Health report on this consultation, which was not published until 11 months after the end of the consultation period, stated that the government would wait for emerging evidence from Australia (Department of Health, 2013).

Normally, tobacco control policies are protected from the vested interests of TTCs by the Framework Convention on Tobacco and Control (FCTC), which has been signed by over 180 countries around the world, including the UK. However, public consultations in the UK are also governed by a piece of legislation called Better Regulation, a key feature of which is to include businesses and other vested interests in the process of public policy-making. There was therefore a clear tension between the FCTC and Better Regulation when it came to this public consultation.

A paper recently published in BMJ Open by researchers at the University of Bath, part of the UK Centre for Tobacco and Alcohol Studies (UKCTAS) has investigated the ways in which the four largest TTCs used the Better Regulation framework to influence the government’s decision on standardised packaging (Hatchard et al, 2014). Hatchard and colleagues compared the evidence submitted to the consultation by the TTCs and that submitted by the researchers from Public Health Research Consortium in their systematic review. The evidence from both groups was assessed for its policy relevance and its quality.

Methods

The researchers only analysed evidence which supported the claim that standardised packaging ‘won’t work’ (other evidence addressed the concern that standardised packaging would have other unintended consequences, or that the policy process itself was flawed). The authors categorised the evidence presented in both the TTCs responses and the systematic review according to the following criteria:

- The subject matter of the evidence, to assess whether it was relevant to the policy. Evidence was considered relevant if it focussed on standardised packaging and parallel if it focussed on other tobacco issues, or issues unrelated to tobacco.

- The independence of the evidence, as a measure of its quality. Given the vested interests of the TTCs in preventing standardised packaging policies, research was considered independent if it was not tobacco industry funded or linked.

- The peer-review status of the evidence as a second measure of its quality. Peer-reviewed articles, which appear in peer-reviewed journals have been shown to be of better quality to other research outputs.

Evidence was included in the analysis if it was relevant to plain packaging, independent from industry funding and peer reviewed

Results

In total, the TTCs submitted 143 pieces of evidence to the public consultation, 77 of which addressed their concern that standardised packaging ‘won’t work’. The systematic review of the evidence included 37 studies, each of which addressed the effects of standardised packaging.

-

Subject matter

- While 17 out of the 77 pieces of evidence submitted by the TTCs directly addressed standardised packaging

- All the evidence in the systematic review did

- Independence

- Of the 17 pieces of TTC evidence addressing standardised packaging, 14 were industry funded

- None of the evidence in the systematic review was industry funded

- Peer-review

- None of the 17 pieces of TTC evidence addressing standardised packaging was peer-reviewed

- Whilst 21 of the 37 studies in the systematic review were

The 17 pieces of TCC evidence addressing standardised packaging were therefore shown to be of lower quality (in terms of both independence and peer-review status) than the 37 pieces of evidence in the systematic review.

The quality of evidence included in the TTC submission was lower than the evidence included in the original DH review

Conclusions

There are three main findings of this analysis:

- The TTCs submitted a large volume of evidence, but only a minority actually focussed on standardised packaging itself, and most of this had a link to the tobacco industry. The authors state that the volume of the TTC evidence submitted to the public consultation, along with the lack of relevance, and quality of this evidence, may have imposed costs on the Department of Health, possibly contributing to the 11 month delay of the publication of the report on standardised packaging.

- The quality of the TTC evidence on standardised packaging was of lower quality (in terms of both independence and peer-review) than that included in the systematic review. In addition, much TTC evidence was either relevant but lacking in quality, or of higher quality but not relevant. The authors suggest that this higher quality but irrelevant evidence may have been included to add legitimacy to the TTCs arguments.

- Industry funded or linked evidence was less likely to be peer-reviewed than evidence not linked to the industry. In the consultation guidelines, there was no requirement for submissions to declare any conflict of interest, or state whether the evidence was independent from the corporation submitting the evidence. All four of the TTCs submitted industry funded or linked research without explicitly acknowledging this, and this lack of transparency was flagged by the authors as a cause for concern for the policy process.

It seems likely that the TTC submission caused significant delays in the publication of the DH report on plain packaging

The authors conclude that the Better Regulation process gives corporations the potential to unduly influence the policy process. Given that the FCTC states that tobacco control policies should be protected from the vested interests of the tobacco industry, the other 177 countries which are signatories to the FCTC should implement clear guidelines on how to deal with TTC submissions to consultations. In order to do this, the authors make two suggestions:

- Conflict of interest declarations for each piece of evidence cited should be made mandatory.

- Policymakers should use the rating framework used in this study (relevance, independence and peer-review status) to evaluate the evidence submitted to consultations in order to prioritise high quality, policy-focussed evidence.

The main limitation of this study, which is acknowledged by the authors, is that only proxy measures of evidence quality (independence and peer-review) were used, rather than a validated quality assessment framework. For example, standards of peer-review can vary, being very stringent or more lenient. However, the authors state that these proxy measures, which do not require scientific expertise or extensive data extraction, are the most appropriate for use by policy makers when assessing the quantity of evidence typically presented to them.

The reviewers acknowledge that using a validated quality assessment framework would have been a more reliable way of conducting their review

Summary

The TTCs submitted a large volume of evidence to the public consultation on standardised packaging, but much of this was lacking in quality and / or was not relevant to the debate. It therefore should be treated with caution.

Since this consultation, a new independent review of the evidence for standardised packaging was commissioned by the government in November 2013. This review is currently ongoing, led by Sir Cyril Chantler (the Chantler Review). A more recent study by the same research group at the University of Bath, published in PLOS Medicine, suggests that the evidence submitted by the TTCs to the Chantler Review was just as misleading as that submitted to the consultation, and in particular, the companies misquoted standardised packaging studies and changed their main messages.

The outcome of the Chantler review was published today. This report concludes that it is:

Highly likely that standardised packaging would serve to reduce the rate of children taking up smoking and implausible that it would increase the consumption of tobacco.

Today in the House of Commons, the Under Secretary of State for Public Health, Jane Ellison, has stated that Chantler ‘makes a compelling case’ and that it was ‘very likely to have a positive impact on public health’. Ellison reported that she was therefore ‘currently minded to proceed with introducing regulations for standardised packaging’.

Draft legislation will now be drawn up, alongside a final short consultation, with a view to introduce standardised packaging before the next General Election in 2015.

Links

Hatchard, J.L., Fooks, G.J., Evans-Reeves, K.A., Ulucanlar, S. & Gilmore, A.B. (2014). A critical evaluation of the volume, relevance and quality of evidence submitted by the tobacco industry to oppose standardised packaging of tobacco products. BMJ Open, 4, e003757. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003757.

Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L, McNeill A, Angus K, Hinds K, Kwan I, Thomas J, Hastings G, O’Mara-Eves A. Plain Tobacco Packaging: A Systematic Review (PDF). University of Sterling, 2012.

Consultation on standardised packaging of tobacco products: summary report (PDF). Department of Health, Jul 2013.

Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, Gilmore AB (2014) Representation and Misrepresentation of Scientific Evidence in Contemporary Tobacco Regulation: A Review of Tobacco Industry Submissions to the UK Government Consultation on Standardised Packaging. PLoS Med 11(3): e1001629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629

Chantler, C. Standardised packaging of tobacco: report of the independent review undertaken by Sir Cyril Chantler (PDF). 3rd Apr 2014.

Badenoch, D. Uptake of plain packaging was associated with reduced satisfaction from smoking and increased will to quit. The Lifestyle Elf, 25 Jul 2013.

Featured image of plain packaging: AAP/Lukas Coch.

My first @Mental_Elf blog, written with @MarcusMunafo on plain packaging and the tobacco industry. @BathTR http://t.co/jHm5EeDyLF

Tobacco industry evidence submitted to government on plain packaging found to be either lacking in quality or … http://t.co/imxnvLyS6p

. @BristolTARG ‘s @OliviaMaynard17 on tobacco industry evidence on plain packaging: http://t.co/199Ktbx5za @Mental_Elf @BathTR @UKCTAS

Great blog on plain cigarette packaging from @BristolTARG bloggers @OliviaMaynard17 and @MarcusMunafo http://t.co/DHkz3VHftc

Weighing up the evidence: the tobacco industry’s response to the plain packaging consultation http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

@Mental_Elf We’ve had plain packaging in Aus for years. The commotion died quickly once introduced. Not sure if it had an impact on smoking

Excellent @Mental_Elf blog on plain packaging by @OliviaMaynard17 and @MarcusMunafo of @BristolTARG http://t.co/Bxhz3171tY

Fundamental misunderstanding of FCTC 5.3 transparency guideline. Govt should understand those they regulate. http://t.co/73RbjRhTZk”

Bristol scientist blogs on today’s move by Government to introduce standardised cigarette packs http://t.co/kipEQAMRr7 @OliviaMaynard17

Plain packaging is in the news today @nhssmokefree @ASH_LDN @CR_UK @TheBHF Please read our blog: http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

Tobacco industry evidence plain packaging found to be lacking in quality and irrelevant http://t.co/kEOFPX5E3c via @sharethis

How did the tobacco industry attempt to influence government policy on plain packaging? http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

More propaganda from the tobacco industry around plain packaging. A nice summary from @OliviaMaynard17 here: http://t.co/RYgALkEVjA

Plain packaging will reduce the rate of children taking up smoking, says Chantler review out today http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

Chantler review expects standardised packaging, over time, to contribute to a reduction in the prevalence of smoking http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

@Mental_Elf you might be interested in this take on it from our researchers at Bath: http://t.co/O7CQnR77pP …

“@Mental_Elf: How did ciggy co’s try 2 influence govt policy on plain packs? http://t.co/Od6i3qnHh2” Free fags/cash in plain Brown wrapper??

How the tobacco industry tried to manipulate the evidence to argue against plain packaging http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

Branded packaging contributes to increased tobacco consumption in adults and children, says new Chantler review http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

Chantler review finds no convincing evidence that standardised packaging would increase the illicit tobacco market http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

How the tobacco industry used the Better Regulation Framework to influence the plain packaging debate http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

Chantler review paves the way for plain packaging before the next general election http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

The evidence @davidjbuck @Mental_Elf Chantler review paves way for plain packaging before the next general election http://t.co/T6tYHc7Ig3

Don’t miss: Review highlights lack of tobacco industry transparency in the gov’t plain packaging debate http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

ICYMI @OliviaMaynard17 on lack of tobacco industry transparency in the plain packaging debate: http://t.co/199Ktbx5za @Mental_Elf

Influencing gov’t policy with poor quality evidence. Plain packaging and the tobacco industry http://t.co/NXEKK60xH9

“@Mental_Elf: Influencing gov’t policy with poor quality evidence. Plain packaging & tobacco industry http://t.co/dfghcGigii” @BMJ_Open

@trished @Mental_Elf @BMJ_Open considering harm from alcohol: same treatment should follow for labelling alcohol on bottles, cans and taps

Tobacco industry evidence to govt on plain packaging found to be lacking in quality or irrelevant http://t.co/KQ9Doiqf8J

Mental Elf: Tobacco industry evidence submitted to government on plain packaging found to be either lacking in… http://t.co/FcIl5eT1cN

Plain packaging will reduce the rate of children taking up smoking, says Chantler review out today http://t.co/kizFm4MMn5 or boost fake cigs

Plain Packs, big tobacco, quality of evidence and vested interests. A classic tale…. http://t.co/8gLCjtdIio