One of the legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the harmful levels of alcohol consumption by a significant proportion of drinkers (Finlay & Gilmore, 2020). There is no doubt that alcohol causes a range of physical and psychological health problems and, unfortunately, accounts for a significant number of premature deaths (NHS, 2022).

This means that we need to improve our understanding of how those at risk of developing problems attempt to independently moderate their consumption of alcohol. This is exactly what Sasso and colleagues (2022) attempted to do in their investigation of implemented strategies to reduce drinking, alcohol consumption, and usual drinking frequency among UK drinkers.

Alcohol causes a range of physical and psychological health problems – are there effective strategies to reduce consumption?

Methods

Using data held by a market research company the authors selected 49,204 people who reported attempting to cut down their intake of alcohol. They were able to compare this group with 60,201 people who reported that they were not cutting down on their drinking. The sociodemographic characteristics of both groups did not vary significantly.

The participants were asked to keep a diary for seven days detailing how often they drank alcohol and how much they consumed. They were then asked about how they tried to moderate their drinking and asked to select one or more of these moderation techniques:

- Drinking on fewer occasions

- Having fewer drinks on occasions when you have a drink

- Having smaller sizes of drink

- Choosing drinks with a lower alcohol content

- Drinking soft drinks

- Drinking alcohol free beer or wine

The statistical analysis employed by the research team aimed to uncover what the relationship was between these moderation techniques and levels of alcohol consumption recorded by the participants in their one week diary.

Results

The most popular technique used by the participants (60%) was cutting down the number of drinking sessions, followed by trying to reduce the number of drinks per week (42%). Less than 10% used low alcohol or alcohol-free products, making this the least popular technique. This surprised me given the wider popularity and range of alcohol-free products now available in the UK.

62% used a single technique to minimise alcohol consumption, while 38% used more than one of the six techniques they were asked to identify. Again, this is an interesting finding, as it is the minority that use multiple techniques rather than relying on just one.

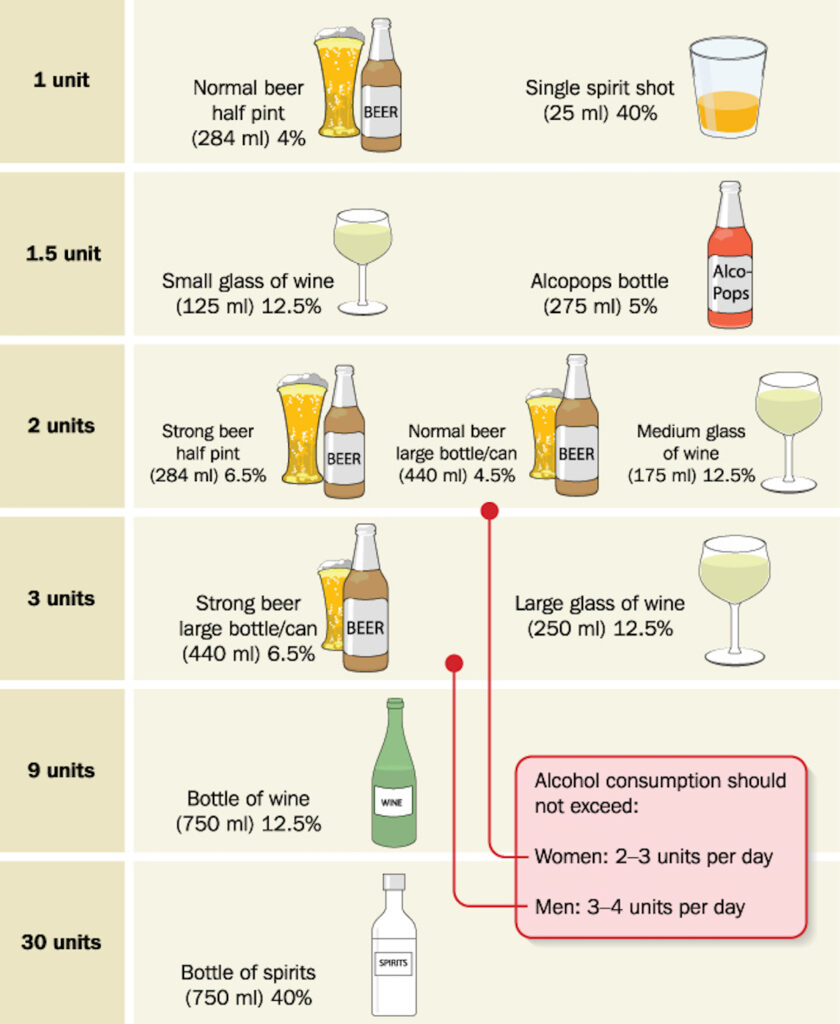

Perhaps it’s not unexpected to learn that those attempting to cut down drank a higher number of units of alcohol per week, at 25 units compared to 22 units for those not considering moderating their use of alcohol. For those not sure about how much a unit of alcohol is, Drinkaware provides both a guide and a unit calculator, so people can see how many units you consume.

The most popular strategies to cut down alcohol intake used by the participants was reducing the number of drinking sessions and number of units during the week.

Conclusions

The authors of the study concluded:

This analysis provides a useful platform for further work, using prospective or intervention designs, to test the relative effectiveness of different moderation strategies for alcohol consumers who want to reduce their alcohol consumption.

People who adopted a mix of strategies to moderate alcohol consumption drank less during the week.

Strengths and limitations

This study was not attempting to find out which moderation technique was effective in reducing alcohol consumption, rather it was aimed at exploring details of consumption and comparing this with the type of technique employed to moderate drinking. The authors are clear about this and rightly suggest a longer-term study would help unpick some of this and be of benefit to this group of high-risk drinkers.

It is worth noting that the those attempting to cut down were drinking at least once a week, with anyone reporting drinking once a month or less being excluded.

As this research relies on self-reported information with no independent check it is difficult to know what effect, if any, this had on the results. It is possible that participants underestimated how much they drank and overestimated their moderation techniques. Alcohol consumption and higher levels of drinking are prone to both internal and external stigma.

Longer-term investigation of alcohol moderation strategies could suggest techniques most effective for people at high-risk for alcohol misuse.

Implications for practice

This is an important study as it explores how people independently try to reduce their consumption of alcohol. These participants were trying to moderate their drinking without any professional support. Although there is evidence suggesting that people who drink at harmful levels benefit from specialist treatment, not everyone who would benefit accesses this type of support. This can be for a range of reasons, such as the support not being available in their local area through to negative beliefs around specialist treatment and those that use mental health services. Whatever the reason, it is clearly important that we understand what helps this group and how they can achieve their goal of cutting down on alcohol.

Overall, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that those that adopted a mix of strategies drank less overall but, unfortunately, when they did drink, they consumed more alcohol.

A useful piece of intelligence uncovered by the team is that age, drinking frequency and openness to try new alcoholic drinks all help to predict the type of moderation strategy used. This, as the authors point out, could help public health interventions more targeted and hopefully successful.

With the future looking bleak for public health budgets due to the current political focus on economic growth, a growing number of people who have problems with alcohol will be left to their own devices. Anything we can glean about what works when trying to cut down alcohol and, therefore, reduce risks to health should improve their chances of success. That has the potential to save lives, this is research at its best.

Public health interventions could target people based on age, drinking frequency and openness to try new alcoholic drinks.

Statement of interests

No conflict of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Sasso, A., Hernández-Alava, M., Holmes, J., Field, M., Angus, C. and Meier, P., 2022. Strategies to cut down drinking, alcohol consumption, and usual drinking frequency: Evidence from a British online market research survey. Social Science & Medicine, 310, p.115280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115280

Other references

Drinkaware, Alcoholic drinks and units – https://www.drinkaware.co.uk/facts/alcoholic-drinks-and-units

Finlay, I. and Gilmore, I., 2020. Covid-19 and alcohol—a dangerous cocktail. BMJ, 369. https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1987

NHS (2022). Risks alcohol misuse – https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/alcohol-misuse/risks/

Photo credits

- Photo by Kelsey Chance on Unsplash

- Photo by Jossuha Théophile on Unsplash

- Photo by Sangria Señorial on Unsplash

Alcohol consumption is intertwined with emotions, behviours, environment, social factors, and beliefs in ways which are complex and individualized. Damage caused by alcohol consumption to self and others is often hidden. I am fortunate to be able to reflect that a life lived without alcohol is richer and more enjoyable.