Recent years have seen an increased interest in ‘psychedelics’ as potential psychiatric treatments (Bird, 2019). There have been some promising results in pilot studies administering psychedelic drugs to patients with “treatment-resistant” mental illness, including this one blogged a few years ago by Sir Iain Chalmers (Chalmers and de Beyer, 2016).

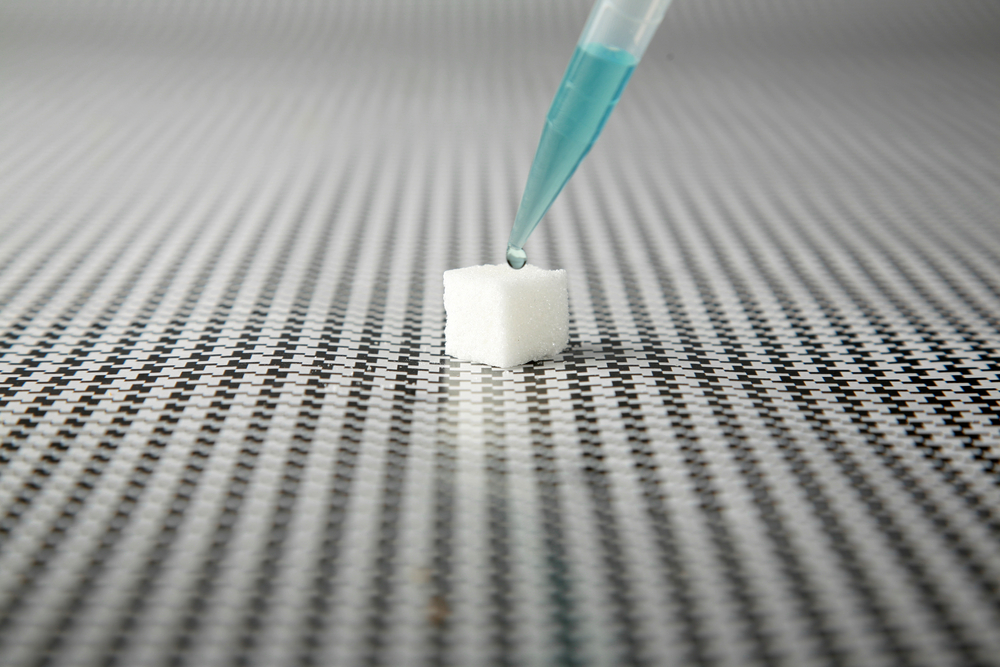

LSD (Lysergic Acid Diethylamide) is a psychedelic drug and its therapeutic use was first researched in the 1960s (Rucker et al., 2018). The study of LSD as a treatment for mental health problems came to a grounding halt due to increasing recreational use, safety concerns and scheduling restrictions (Nutt, 2015), but there has been a recent resurgence; first in healthy volunteers, but then in mental health patients (Rucker et al., 2018). A meta-analysis of ‘pre-prohibition’ studies found LSD to be effective in treating alcohol use disorder (Krebs & Johansen, 2012). Another review concluded that LSD deserved further investigation as a treatment for mood disorders (Rucker et al., 2016).

The context in which psychedelic drugs are administered, also referred to as ‘set’ and ‘setting’, is important (Carhart-Harris et al 2016):

- ‘Set’ refers to a participant’s thoughts and expectations. In clinical use, this may involve psychotherapy to prepare the participant.

- ‘Setting’ refers to the physical environment where people receive the drug; a comfortable room, music, the presence of supporters during the session. Other considerations are about including post-drug integration sessions.

It is not clear what amount of potentially costly psychological support is sufficient (Rucker et al, 2018). New research into LSD is costly and time-consuming, in part due to drug scheduling restrictions (Nutt, 2015).

Fuentes et al., 2020 aimed to guide such considerations by providing an overview of LSD research. They conducted a systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) testing LSD as a psychiatric treatment.

LSD research started in the 1960s, but dropped off when LSD was classified as having no accepted medical use. Should we be thinking again about the therapeutic use of LSD for mental illness?

Methods

The authors conducted a systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. They searched databases including PubMed and the MAPS bibliography of psychedelic studies (non-profit organisation for psychedelic research) and they manually looked through references from eligible publications.

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts. They only included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of LSD (active or non-active comparators) involving patients with a diagnosis of mental illness, excluding healthy volunteers. Quality was scored by two authors using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment tool.

The authors extracted data on treatment/control (dosage, frequency and duration of treatment), patient characteristics (age, gender, and diagnosis), trial design (set and setting considerations, length of follow-up). For the outcomes, they extracted change scores from baseline or endpoint, side effects, overall tolerability.

Results

Out of 43 studies screened in detail, the authors included 11 in their review. Many studies were excluded because they did not have a control group or did not randomise participants. The publication dates ranged from 1966 to 2014 and the trials were conducted in Canada, USA and Switzerland. The majority of them had a low risk of selection, attrition, detection and reporting bias, while five out of 11 had a high risk of bias related to participant and personnel blinding.

The studies recruited patients with the following diagnoses: alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 7/11 trials, heroin use disorder (1/11), ‘neurotic’ or ‘psychoneurotic’ diagnoses e.g. depression, anxiety (1/11), AUD or ‘neurotic’ diagnoses (1/11), and anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases (1/11).

Drug, dosing, control

Looking at the included studies, 20 – 800 mcg of LSD was administered to 567 patients. There were 404 control participants. Seven studies used an active control (an alternative psychoactive drug or a lower LSD dose) and four studies had a control group who received no drug.

Set and setting

In four studies, patient preparation ranged from brief orientation to more extensive preparation, which aimed to promote the therapeutic experience. During the LSD session, five studies delivered psychotherapy, while others commented on using a comfortable physical environment. At least two of the studies included ‘integration’ sessions where participants discussed the LSD experience with a therapist. Possibly the studies that delivered psychotherapy also included integration sessions, but it isn’t clear.

Efficacy

- Three alcohol use disorder (AUD) studies found a significant effect of LSD on abstinence or drinking behaviour. For two studies this was sustained at 6-12 months and for one study only up to 2 months. One study found general health to improve in the LSD group, but no effect on alcohol use. The other four AUD studies found an improvement in all treatment groups, with no significant difference between LSD and control.

- The study that tested LSD for heroin use disorder found a significant effect of LSD on abstinence rates at 12 months.

- Two trials examined LSD as a treatment for “neurotic” symptoms, finding that LSD had a significant effect on symptoms compared to control treatments. In one study general health benefits were sustained to 12 months, while in the other, the improvements were not seen past 6-8 weeks.

- LSD reduced anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases at two months.

There were just two serious adverse events reported.

According to this review, LSD may be effective in increasing abstinence from alcohol and heroin use disorders, and in reducing anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

LSD is a potential therapeutic agent in psychiatry.

The strongest evidence is for the use of LSD in the treatment of alcoholism.

LSD is a potential therapeutic agent in psychiatry, but could it have widespread impact? Currently the evidence does not support this.

Strengths and limitations

This review included older studies that are difficult to access electronically, so serves as a very useful reference point for older literature. In addition, a lot of past LSD studies didn’t have control groups so it’s very useful to have a review that only includes controlled studies. Psychedelic research is relatively novel and growing, thus there are many potential research implications from this review. Despite the limitations of the older studies, the authors rated the risk of bias in a lot of the categories as low, which is encouraging for drawing conclusions.

However, the search involved just the PubMed database and MAPS bibliography. It would have been interesting to consider unpublished data, e.g. by searching registered trials. I would have liked to see the authors comment on the possible relationship between dose and efficacy, and to examine if there was a relationship between set/setting and efficacy to stand this review apart from previous ones. The authors do comment that the therapeutic value of LSD is related to variables such as set and setting, but this is not totally clear in the results.

Lastly, heterogeneity of the studies precluded a meta-analysis, making it harder to draw firm conclusions. There are differences between how the earlier studies were conducted and what we do now, which limits application of the results to modern research. Diagnostic categories were different. The definition of ‘control group’ varied between studies, and the validity of a control where no substance is administered is questionable. Some studies had large imbalances in numbers between the control and treatment groups. Furthermore, the quality of the studies varied, with many having a high risk of bias for blinding.

It is valuable to have a detailed review of older literature, but an exploration of the relationships between set/setting and efficacy would be interesting to be included.

Implications for practice

The modern approach to trials of LSD and psychedelic drugs is to pay attention to patient preparation and aftercare. There was no consistent approach amongst these studies. Nonetheless, the rate of adverse events was low, including in trials giving large doses with no preparation or therapy. This suggests there is scope for research into what amount of preparation and psychotherapy is essential.

Generally, LSD appears to be safe and has the potential to be effective. The lack of consistency may have limited these studies’ ability to find an effect of LSD.

On the basis of this review, we cannot conclude that there is strong evidence of positive effects. However, there is evidence to suggest that changes to drugs scheduling policy to allow for easier research into LSD would be justified.

Psychedelic research inspires a lot of excitement; the danger is that this turns into hype. There are two trials of LSD registered on clinicaltrials.gov for psychiatric disorders, so watch this space!

LSD delivered within a controlled therapeutic setting appears to be safe and has the potential to be an effective treatment for some mental illnesses, but it’s early days and much more work needs to be done.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Fuentes, J. J., Fonseca, F., Elices, M., Farré, M., & Torrens, M. (2020). Therapeutic Use of LSD in Psychiatry: A Systematic Review of Randomized-Controlled Clinical Trials. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10, 943.

Other references

Bird, C. (2019). How can psychedelics treat mental illness? #PsilocybinMedicine. The Mental Elf. Last accessed: 8 May 2020.

Chalmers, I. and de Beyer, J. (2016). Magic mushrooms promising for treatment resistant depression. The Mental Elf. Last accessed: 8 May 2020.

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Roseman, L., Haijen, E., Erritzoe, D., Watts, R., Branchi, I., & Kaelen, M. (2018). Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 32(7), 725–731.

Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P. Ø. (2012). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 26(7), 994–1002.

Nutt D. (2015). Illegal drugs laws: clearing a 50-year-old obstacle to research. PLoS biology, 13(1), e1002047.

Rucker, J. J., Jelen, L. A., Flynn, S., Frowde, K. D., & Young, A. H. (2016). Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. Journal of psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 30(12), 1220–1229.

Rucker, J., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200–218.

Photo credits

- Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

- Photo by Jr Korpa on Unsplash

- Photo by Nick Fewings on Unsplash

- Photo by Àlex Rodriguez on Unsplash

- Photo by Philipp Berndt on Unsplash

- Photo by Laura Ockel on Unsplash

thanks. very interesting

LSD is a Life.Saving.Drug and the initial hippie flower child at Woodstock needs to be forgotten. Doctors need to study and prescribe because if we didn’t know it as LSD the hippie drug it would be on time magazine as the suicide cure because it saved my life and I didn’t get high. Small amounts throughout the day and was normal as an Advil. Depression was removed from my brain I could feel the weight loss of the disease gone. I was doing dishes and folding clothes, not in a altered state. Many things I could go on about but this can save lives from suicide it’s very real and needs to be prescribed by the fda and doctors everywhere. 💯 from the heart