Back in 1992, during the American recession, Bill Clinton secured the presidency by tuning into the concerns of voters, famously saying it was the economy stupid. Ten years after the 2007 financial crash, mental health and drug treatment services continue to feel the impact of austerity. The problems faced by these services and the people they serve have to recognise this fact.

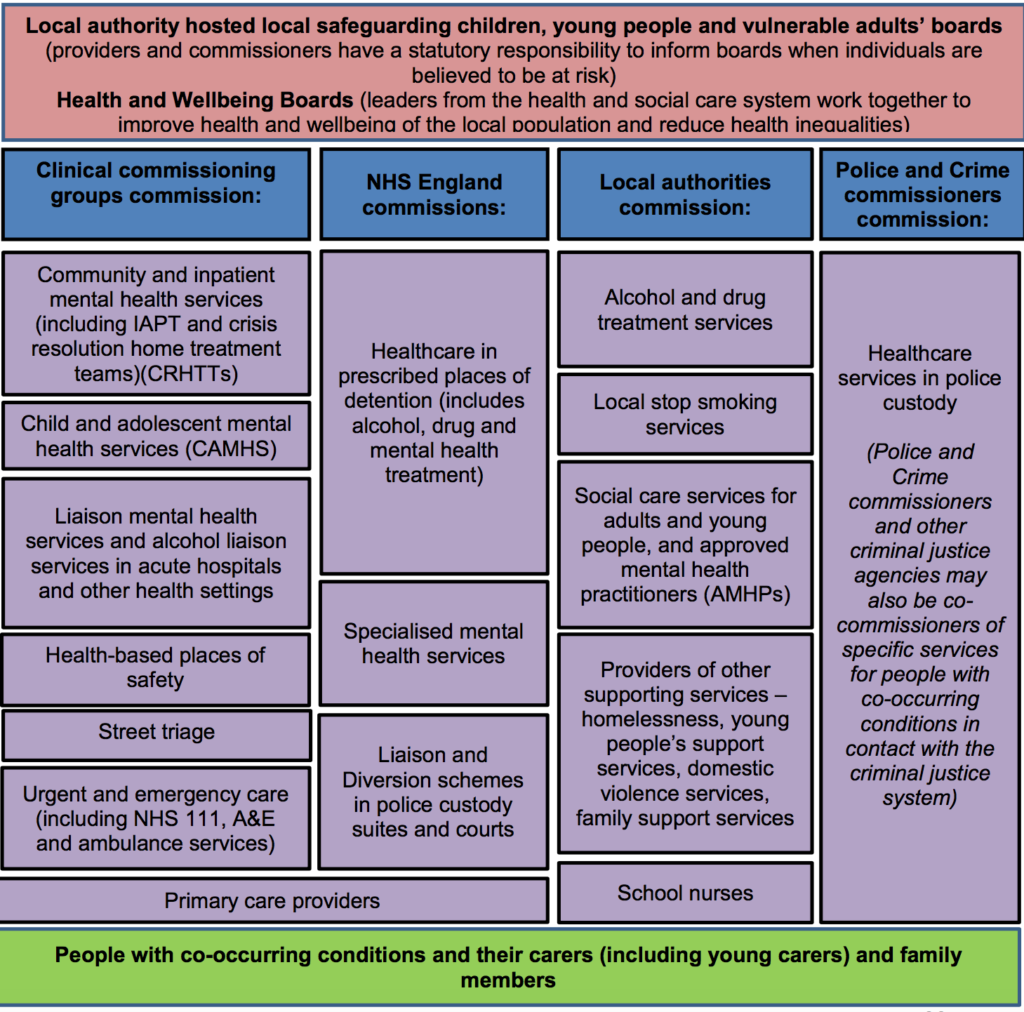

The last year has seen a flurry of guidance and policy activity for dual diagnosis (Hamilton, 2017). But it’s not guidance that’s going to radically change things for people with co-occurring problems, it’s something more fundamental. As recent NICE guidance on the subject recognised when it pointed to the separate funding streams for mental health and drug/alcohol treatment; these distinct funding systems are hampering integration, said NICE.

Public Health England, a body that has itself faced savage budget cuts over recent years, has recently published new guidance: Better care for people with co-occurring mental health and alcohol/drug use conditions (PDF).

Guidance isn’t going to radically change things for people with co-occurring drug and mental health problems. So what is?

The guidance aims to encourage different agencies to work together to improve care for people who use drugs and have mental health problems. Two principles underpin this ambition:

- It’s everyone’s job. Commissioners and providers of mental health and alcohol and drug use services have a joint responsibility to meet the needs of individuals with co-occurring conditions by working together to reach shared solutions.

- No wrong door. Providers in alcohol / drug, mental health and other services have an open door policy for individuals with co-occurring conditions, and make every contact count. Treatment for any of the co-occurring conditions is available through every contact point.

The guide is intended to cover all ages, all settings and every combination of substance use and mental health. This is welcome as it doesn’t get bogged down in narrow and technical definitions of dual diagnosis. This might not please everyone, but at least it’s simple. This also represents a formal move away from the Department of Health definition of dual diagnosis, which focussed on severe mental health problems and hazardous drug use.

Although most issues are covered briefly, the document provides some practical points that commissioners and providers should consider. These include therapeutic alliance, optimism and workforce training needs. The guide will also be handy for those not familiar with the specific needs and challenges that people with co-occurring mental health and drug use have. There is even an appendix with 33 questions commissioners should ask when commissioning or monitoring services.

The challenges of commissioning and providing services for people with a dual diagnosis are not unique to the United Kingdom. Australia has recently published guidelines (PDF) on this issue. Kevin Gournay helped author the Australian guidelines, concluding that both the UK and Australia share the same challenges (Gournay, 2017). Kevin calls for greater investment in the workforce and integration of the disparate services. I share this ideal, but in the UK austerity following the financial crash has seen mental health and drug treatment funding reduced, with no indication that this will change over the coming years.

Is austerity the answer not the problem?

With both mental health and drug treatment facing real cuts to their budgets by a Government that is shrinking the state, might this turn out to be beneficial for people with a dual diagnosis?

Thirty years of guidance and policy haven’t persuaded mental health and drug treatment services to work together effectively, but money might. It is understandable why both camps zealously guard their diminishing budgets, but with all the ‘efficiencies’ gained there might be only one way left, to integrate. In the same way people with a dual diagnosis have interconnected problems they need a service response that is joined up. As austerity continues to dismantle and dismember the state this might be the catalyst that is needed to fully integrate mental health and drug treatment services.

The people are not the problem, the infrastructure and systems are. So what should we do?

It seems there are three options:

- We keep tinkering around the edges with policy and guidelines

- Mental health and drug treatment are fully integrated

- Local commissioners innovate for their geographical area of responsibility

Individually and collectively we should not give up seeking solutions for this group of people, but in these economically austere times investment is unlikely. So whatever we do, it will have to involve spending less while need grows. Austerity might be a blessing in disguise.

Austerity: a blessing in disguise when it comes to dual diagnosis services?

Links

Primary paper

Public Health England. (2017) Better care for people with co-occurring mental health and alcohol/drug use conditions (PDF). Public Health England, 26 Jul 2017.

Other references

Gournay K. (2017) Editorial: Guidelines on the management of co-occurring alcohol and other drug and mental health conditions in alcohol and other drug treatment settings in Australia. Advances in Dual Diagnosis, 10,1,1-4.

Hamilton I. (2017) From famine to feast as dual diagnosis features in new United Kingdom government policy and strategy. Advances in Dual Diagnosis,10,3,120-122

We have a dual diagnosis worked embedded in the local cmhts which works well I think. He assesses,refers in to local D+A service and acts as expert resource for staff. But as the cmht only commissioned for people w SMI and for ‘shortest possible time’ its vital to have good local substance services