The move to making NHS estates smoke-free has been enshrined in policy for a number of years. The desire to stop people smoking is clearly linked to potential health benefits, yet hospitals continue to “collude” with individuals to enable them to carry on smoking. Travelling around hospitals you often see patients being wheeled outside to smoke, or staff turning a blind eye to patients or colleagues smoking. This is not just in mental health settings.

However, the banning of smoking in mental health settings has been subject to considerable debate, for example:

- The 53rd Maudsley debate: “This house believes that smoking should be banned in psychiatric hospitals“

- The salient argument by leading mental health blogger @Sectioned_: “A total smoking ban for detained psychiatric patients stinks of coercion“

- Various smoke-free hospital blogs on The Mental Elf.

Arguments span health, legal and human/civil rights domains. However, one key point you often hear against implementing smoke-free policies are fears about a potential increase in violence as a result. This blog focuses on a systematic review by Spaducci and colleagues, which investigates violence that is related to the introduction of smoke-free policies. It’s worth noting that the title of this review is somewhat general and misleading: “Violence in mental health settings: A systematic review”.

The desire to stop people smoking is clearly linked to potential health benefits, yet hospitals continue to “collude” with individuals to enable them to carry on smoking.

Methods

A systematic approach was undertaken with the review reporting to PRISMA guidelines and registered on PROSPERO. However, it’s interesting that the PROSPERO registered review has a slightly different name from this publication (Does the implementation of smoke-free policies in mental health settings increase violence? A systematic review). This is an update of a previous review conducted in 2005 by Lawn & Pols, which included 26 papers from 1998 to 2002. In this review it is not clear, although papers dating as far back as 1996 were included. A narrative synthesis approach was undertaken.

Results

- 11 studies were included, most originated from the US.

- All included studies were observational

- 7 cross-sectional studies

- 4 cohort studies

- The studies reported on:

- Physical violence

- Decreased in 1 study

- No change in 3 studies

- Increased in (the short-term) 2 studies

- Verbal violence

- Decreased in 3 studies

- Increased in 2 studies (temporary increase in 1 study)

- Combination of physical/verbal violence

- Decreased in 3 studies

- No change in 1 study

- Increased in 1 study

- Physical violence

- The dates of policy implementation ranged from 1991 to 2014.

The reviewers concluded that the introduction of smoke-free policies generally do not lead to an increase in violence, but can this review confidently answer this question?

Limitations

- Whether or not smoking bans are linked to violence clearly needs to be considered in more depth. The findings of this narrative review appear inconclusive, and certainly combining verbal abuse and violence, and policies which ranged from total bans to partial ones into one paper complicated this. An expression of frustration at not being able to smoke, is not the same as becoming physically violent.

- It also remained unclear whether it was the smoking ban in isolation that was linked to violence. Although some of the papers tried to differentiate between smokers (and variants of this) and non-smokers, it remained unclear whether the violence was triggered by the policy or other factors.

- There is also an issue with the reporting of findings (particularly of violence), with no-change and decreases being grouped together in the reporting.

It’s unclear from the observational studies included in this review whether it is smoking bans that are linked to violence or other factors.

Implications

Smoking has long been a currency on wards, given by staff to reward good behaviour; a trigger for disharmony when you have run out; or means for you to be bullied or threaten by other patients. In some places the only way to get outside is during cigarette breaks. Banning smoking on wards in some regards is similar to banning drugs or alcohol, we know that these things continue regardless of the policies, and how rigorously the policies are implemented has its own perils and pitfalls. There remains the unanswered human rights questions if you are detained under the Mental Health Act is this another violation of your rights, of course the same could be said of other legal substances.

The observational studies focused on the short period of time following the introduction of the smoke-free policy changes. It may be that staff consistently implement the policy at these times. Patients have been made aware that things are changing and so are prepared. Systems have been put into place to provide additional smoking cessation expertise, and nicotine replacement therapies are available. What these studies don’t tell us is what happens after this point; do staff become inconsistent, leave or are they replaced by agency/bank staff, do patient groups change, are cessation systems maintained? Is this compounded when staff leave the premises to smoke only to return to breathe their fumes over you? I have heard of organisations after a period of implementation reverting back to smoking policies over safety fears. These fears may be related to concerns about violence increasing, but also other risks, for example, fires as patients hide lighters and smoke secretly. It is also clear that the role of vaping needs to be considered across the NHS; potentially safer, will this help resolve some of the issues associated with Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT).

It remains perplexing that at a time when smoking cessation services in the community are being reduced, that the demands to stop patients smoking in hospital are increasing. The risk of restarting smoking on discharge are real, these can have a huge impact on the metabolisation of antipsychotics potentially causing relapse and a return to hospital.

Although this review provides a useful summary of the literature, the simple answer remains: we probably don’t know the impact of smoking bans on the broader safety of mental health wards.

The role of vaping needs to be considered across the NHS.

Links

Primary paper

Spaducci G, Stubbs B, McNeill A, Stewart D, Robson D. (2018) Violence in mental health settings: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, Volume 27, Issue 1, February 2018, Pages 33-45.

Other references

Lawn, S., & Pols, R. (2005). Smoking bans in psychiatric inpatient settings? A review of the research. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 39(10), 866-885.

53rd Maudsley Debate: “This house believes that smoking should be banned in psychiatric hospitals”.

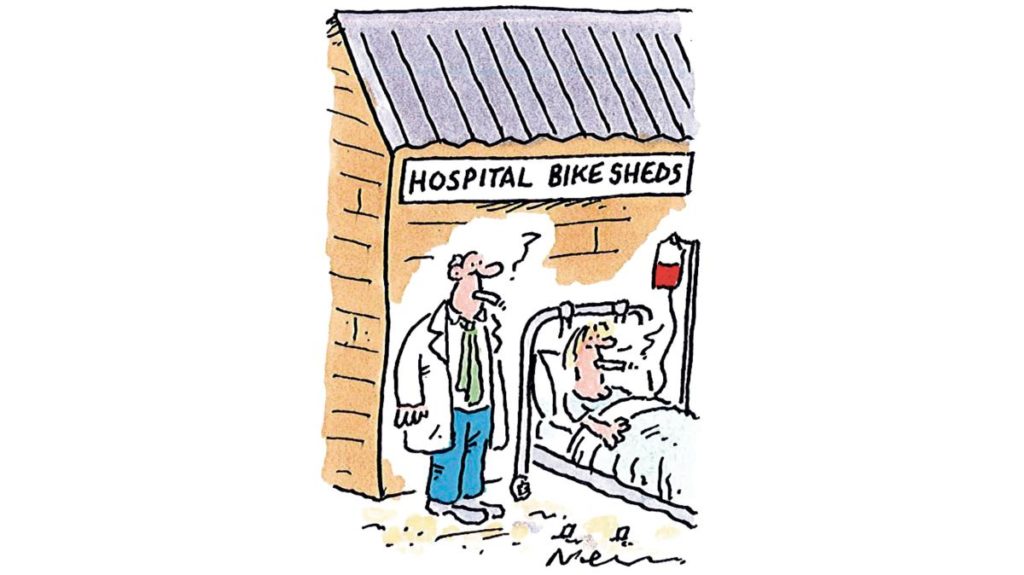

Good carton here in The Times https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/nhs-seeks-ban-on-smoking-in-hospital-grounds-cwwstb0kv

“Collude” https://www.bmj.com/content/356/bmj.j500

A total smoking ban for detained psychiatric patients stinks of coercion @Sectioned_ blog, 7 Nov 2015.

Spaducci G, Robson D, Stubbs B, Stewart D. Does the implementation of smoke-free policies in mental health settings increase violence? A systematic review. PROSPERO 2016 CRD42016036328

Photo credits

- Photo by Justin Casey on Unsplash

- Photo by VapeClubMY on Unsplash

Three years ago, when preparing for the Maudsley debate on banning psychiatric detainees from smoking outdoors, the only research I could find into the effects of the ban was looking at concerns of ward staff. That still seems to be the case.

Is there any research showing that short-term enforced abstinence is an effective means to reduce smoking harm & improves therapeutic outcomes for patients post-release?

I’m still looking.

Dear @Sectioned_

Thanks for your comment. I agree that there are several studies evaluating the concerns of ward staff of implementing smoke-free policies particularly around violence, there are also studies evaluating patient views and experiences of smoke-free hospitals e.g. Hehir and colleagues (2012) – evaluation of a smoke-free forensic hospital: patients’ perspectives on issues and benefits https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22524262 and Filia and colleagues (2015) Inpatient views and experiences before and after implementing a totally smoke-free policy in the acute psychiatry hospital setting https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/inm.12123 as some examples.

There are other studies also measuring patient attitudes and experiences of the policy.

In terms of evaluating enforced abstinence Brose and colleagues (2018) published a review evaluating interventions to maintain abstinence post-discharge from a setting where there was enforced abstinence https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/maintaining-abstinence-from-smoking-after-a-period-of-enforced-abstinence-systematic-review-metaanalysis-and-analysis-of-behaviour-change-techniques-with-a-focus-on-mental-health/5793A065F72B50ADF656D25A6856C8E7 (I think this has been referred to in the twitter thread).

Stockings and colleagues published a review looking at the impact of a smoke-free psychiatric hospitalisation on patient smoking outcomes. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0004867414533835

Hope this is useful.

[…] to Nationalelfservice.net: […]

Dear Professor Baker and The Mental Elf,

Many thanks for highlighting our systematic review in your blog about smoke-free policies on mental health wards and violence.

We agree that it is difficult to define the exact relationship between smoke-free policies and violence and further research is needed to understand the implications of these policies. The primary studies included in the review were limited by their methodologies – other factors which may have contributed to violence were not accounted for in their analysis and as you mentioned, follow-up periods were often short. Where we were able to, we differentiated between physical and verbal violence, however some of the primary studies didn’t distinguish between the types of violence that occurred.

We tried to overcome some of the limitations of previous studies in this area in another of our studies (https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(17)30209-2/fulltext). We evaluated rates of physical assaults towards staff and other patients 30 months before and one year after implementing a comprehensive smoke-free policy across the South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. We used a more robust research design compared with previous studies and accounted for certain demographics and clinical characteristics which have been reported in the literature as predictors of violence. We found a decrease in violence following the policy, however, we explained how we could not infer causality because of the research design.

As you mentioned cigarettes have long been a currency on mental health wards, and a leading cause of health inequalities. Our group is part of The Mental Health and Smoking Partnership (http://smokefreeaction.org.uk/smokefree-nhs/smoking-and-mental-health/mental-health-and-smoking-partnership-members/) which aims to address the disparity in smoking rates between those with and without a mental health condition. The Partnership brings together Royal Colleges, third sector organisations, academia and service user groups to improve treatment for smokers with a mental health condition and support smoke-free policy implementation.

Thanks for highlighting this important issue.

“We evaluated rates of physical assaults towards staff and other patients” … “we explained how we could not infer causality because of the research design.”

The flaw in this research study based on recorded incidents of violence is the Maudsley and other mental hospitals in the NHS do not record incidences of staff on patient violence. The Maudsley in recent times have started to publish the recorded incidents of patient on staff violence, relative/friend on staff violence, and staff on staff violence statistics, however, the Maudsley and others as aforementioned, fail to publish staff on patient violence, and pertinent in this instance incidents of nurse on patient violence.

To be quite clear, when I say “staff on patient”, that is, unprovoked acts of physical violence by staff on their patients. And not verbal abasement of patients, such as, members of staff expressing an attitude along the lines to their unemployed mental patients of “I am superior to you because I pay tax and you don’t.”

John Baker as the Chair of Mental Health Nursing is caught in a double bind between accurate research and admitting to nurse on patient violence as a reoccurring and unrecorded phenomena.