It’s hard to tell on the face of it what the knock-on effects of using cannabis are with the wash of media attention, political messages, and people trying to avoid sounding like a massive downer.

But when looking at the clinical evidence overall, how can we discern the true state of affairs, and how much is actually known about the psychological harms and benefits of cannabis?

Cannabis has recently become legal in states across the US, with European countries whispering about loosening the legal straps a little more. Clearly the hype around it’s increased availability is a testament to how strongly people feel about the freedom to use the plant, and recently there have also been a number of studies suggesting moderate evidence for its use to treat chronic pain and muscle spasticity.

However, the evidence for the association between cannabis and psychosis has been mounting, and it was time that the results across a number of studies were pooled to report where the evidence is currently pointing: is cannabis a menace to the development of psychosis or a happen-stance?

Is cannabis a menace to the development of psychosis or a happen-stance?

Carney and colleagues at the University of Manchester recently published a meta-analysis to examine this question (Carney et al, 2017). This blog is a summary of that review.

But before we begin, a small note about the basic biology of cannabis:

- Cannabis is comprised of a whole host of different compounds (at least 144), known as cannabinoids; however the most focused upon in the research are Delta-9-tetrahydrocannbinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD) as they are the most abundant.

- The dynamic between THC and CBD has often been described as a ‘yin and yang’ relationship by Prof Val Curran, a professor in psychopharmacology at UCL:

- THC is the main psychoactive compound, and produces the classic ‘high’ effects such as euphoria, hallucinations, paranoia, and anxiety

- CBD has been demonstrated to have anti-anxiety properties and counter some of the effects of THC, and has even been suggested to hold anti-psychotic properties.

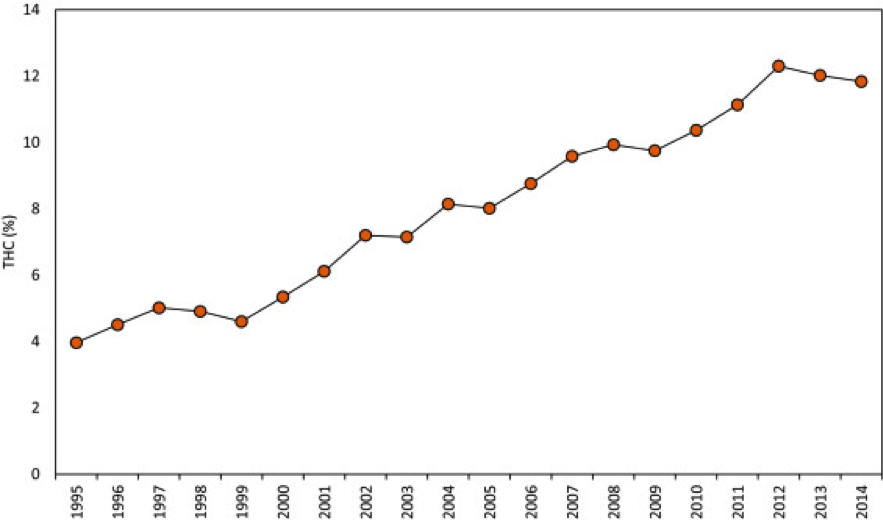

In recent years, the percentage content of THC in cannabis has risen dramatically.

From 1995-2014, THC content in cannabis has nearly tripled in the USA. (Copyright: ElSohly et al., 2016)

In this study, authors aimed to analyse the evidence examining cannabis use in individuals at ultra-high risk (UHR) of developing psychosis. Individuals in the UHR category are defined as:

- Experiencing attenuated psychotic symptoms e.g. mild hallucinations, social withdrawal and apathy

- Experiencing occasional and brief psychotic experiences

- Having a genetic risk, combined with a decline in functioning.

This study wanted to answer whether UHR individuals had higher rates of current and lifetime cannabis use and have higher rates of cannabis use disorders compared to healthy controls, and whether UHR individuals had more frequent and severe positive and negative symptoms than non-cannabis using UHR individuals.

Methods

Authors included studies with UHR participants who currently used or have used cannabis, or had current/lifetime cannabis use disorders.

After searching five scientific databases, 30 eligible cross-sectional, intervention, and/or longitudinal studies were found across 10 different countries, including the UK, Netherlands, USA, and Canada. 29 of these were included in the meta-analysis. This included a grand total of 4,205 UHR individuals, and 667 healthy controls.

Based upon the data retrieved from the studies, authors calculated the risk of developing psychosis and severity/frequency of symptoms associated with cannabis use.

Results

In essence, authors answered their three primary research questions from the current data:

Current and life-time cannabis use

- 26.7% of UHR individuals currently used cannabis and were suggested as more likely to currently use, although this didn’t quite reach significance compared to healthy controls

- 52.8% UHR individuals had used cannabis at some point in their lifetime, which was significantly higher than healthy controls.

Cannabis use disorder

- 12.8% of UHR individuals also had a cannabis use disorder, and this was significantly more likely to occur in UHR individuals compared to healthy controls.

Positive and negative symptom severity

- Positive and negative symptoms overall did not significantly differ between UHR individuals who did and did not use cannabis

- Frequencies of unusual thought content and suspiciousness did significantly differ between groups, with UHR individuals who had used cannabis reporting higher frequencies.

Cannabis can lead to increased experience of paranoia in those with high risk for psychosis (Copyright: spiceaddictionsupport.org).

Discussion

When pooling the data, it looks as though cannabis is used in high frequencies in UHR individuals, and this is significantly higher when compared to healthy controls over a lifetime.

The evidence also supports the role of exacerbated positive symptoms in the development of psychosis; specifically through increased paranoia, unusual thought content, and suspiciousness as an effect of using cannabis. This has implications for the role of positive symptoms in the development of psychosis.

While this study still does not address cannabis as a causal factor in the development of psychosis, it certainly strengthens the association between the positive symptoms of psychosis and high frequencies of cannabis use.

This study has quite a few strengths when coming to these conclusions, namely that such a variety of data was used from numerous countries, and that results from such a large group of participants were able to be pooled.

This study suggests that cannabis is used in higher frequencies in those who are most at risk of developing psychosis.

Limitations and future directions

A limitation of this study is that the chemical composition of cannabis isn’t broken down. Therefore, while we know that in UHR individuals, cannabis as a whole is producing more severe experiences of paranoia and unusual thought content, we don’t know which component is the main offender.

However, when looking at the data into the increase of THC in cannabis over the years, and given other supporting evidence into THC’s role in the experience of paranoia, it seems highly likely that a higher THC content may lead to higher frequencies of psychosis, especially with the recent surge of synthetic cannabis. This may overshadow the characteristics of its other compounds; for example, as CBD has been suggested as a balancing agent to the psychoactive effects of THC, CBD might be a useful antipsychotic tool.

As well as THC potentially being a major factor in the link between cannabis and psychosis, the way that people use cannabis may also alter the effects. A recent meta-analysis reported that smoking tobacco can greatly increase the risk of psychosis, and as cannabis and tobacco are frequently smoked together, it cannot be excluded from the relationship. Check out our Elf Campfire expert discussion on smoking and schizophrenia here.

Given the current findings, and in light of other evidence, it would be interesting to further explore whether individuals who use lower THC cannabis without tobacco (e.g. in a vaporiser) are any more susceptible to experiencing positive symptoms of psychosis than the rest of the population. Once these factors have been controlled for, we can more clearly see the relationship between cannabis and psychosis.

Indeed, a very recent article has called for the control of tobacco, CBD:THC ratios, and polydrug use to be addressed in research further to try and make cannabis as safe as possible.

Authors chat about this article in a podcast for The Lancet Psychiatry.

Conclusion

Cannabis is used in higher frequencies in those who are most at risk of developing psychosis, and is reported to significantly increase experiences of paranoia and unusual thought content.

However, given current evidence, it seems most likely that high THC cannabis, smoking cannabis with tobacco, and the presence of an underlying vulnerability causes psychotic experiences. Hopefully further specific exploration can begin to tease out these complexities and lead to a more evidence based approach to drug policy, regulation, education, and clinical care.

One public health option we should consider is educating people about safer cannabis use.

Links

Primary paper

Carney R, Cotter J, Firth J, Bradshaw T, Yung AR. (2017) Cannabis use and symptoms severity in individuals at ultra-high risk for psychosis: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 1 (11). [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Englund A, Freeman T, Murray R, McGuire P. (2017) Can we make cannabis safer? The Lancet Psychiatry. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30075-5

Ksir C, Hart CL. (2016) Cannabis and psychosis: a critical overview of the relationship. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(2), 1-11. [PubMed abstract]

Photo credits

- Featured image: Copyright TheCannabist.co

- eggrole CC BY 2.0

- By Chmee2 (Own work) [GFDL, CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY-SA 2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons

“higher THC content may lead to higher frequencies of psychosis, especially with the recent surge of synthetic cannabis”

This for me is a strange statement. High THC content has nothing to do with what people call synthetic cannabis. SCRA’s like spice do not contain THC or any compounds that are even structurally related to it.

If we are talking about Marinol which is synthetic THC without the other cannabinoids that would be understandable but i don’t think Marinol is what is being discussed.

There ahould be a clear line between these drugs as they are completely different.

Well SCRAs are structurally related to THC, they attempt to mimic its effects but they are mostly full agonists of CB1 whereas THC and other phytocannabinoids are only partial agonists.

That anyone can confuse the effects of SCRAs with cannabis demonstrates unequivocally that they have no idea what they’re talking about.

[…] https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/substance-misuse/cannabis-psychosis-high-time-revie… […]

[…] https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/substance-misuse/cannabis-psychosis-high-time-revie… […]

I agree with Rock Star. This article is sloppy in the extreme, hardly what one would expect from someone who presumably regards themselves as a scientist.

The evidence for an association between cannabis and psychosis has not been mounting at all. It’s stayed remarkably consistent and weak since 1898 when the Indian Hemp Commission first addressed this theory and found it largely unfounded.

What’s truly astonishing is that despite the almost messianic determination by some researchers to prove this theory and study after study after study there is still no evidence of an causal link. The most one can say is that cannabis might be one of several component factors in such a diagnosis.

Cannabis psychosis research is a cash cow for scientists and that’s what this article is really about. Time for another review (with the inevitable pathetic pun on high)? Really? Another review? Has anything ever been reviewed more extensively and regularly.

No, this is just another bad joke and example of how research effort is so misguided. Millions of people use cannabis for medicinal reasons. Now that would be a positive, constructive and rational direction for any future research efforts. not this endless, futile, repetitive topic of psychosis

Does (or can) cannabis-induced psychosis continue after cessation (i.e., after days or weeks of cessation) of cannabis use? I.e., if someone who is bipolar with psychotic features still psychotic after a month of cessation, does that mean the psychosis was not cannabis induced?