Self-harm is a major public health concern that affects many people, with a lifetime prevalence of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in the UK being as high as 7.3% (McManus et al., 2019). NSSI is especially prevalent in young people, with the average global prevalence at 17.2% for adolescents, and 13.4% in young adults (Swannell et al., 2014). Self-harm is a transdiagnostic symptom (Selby et al., 2012), with people visiting the hospital after an incident being most frequently diagnosed with depression, anxiety, alcohol misuse, and ‘personality disorders’ (Hawton et al., 2013).

Psychotherapy encompasses any evidence-based treatment that involves talking with a mental health professional. Some research has indicated small to moderate effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for reducing self-harm in adults, whilst evidence for dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) is only preliminary (Witt et al., 2021). Murphy et al. (2010) have argued that people who self-harm are more likely to disengage from services.

Haw and colleagues (2023) are the first (to our knowledge) to collate and synthesise patients’ experiences of psychotherapy for self-harm. The main finding is that building a trusted therapeutic relationship was essential for the perceived success of therapy, and that this process was unique to each person. Let’s have a closer look at the review!

Despite affecting a large number of people, little research to date has explored participant experiences of what makes psychotherapy effective at reducing self-harm.

Methods

The authors aimed to gather findings from pre-existing qualitative studies investigating participant experiences of psychotherapy for self-harm. Researchers searched electronic databases for relevant studies. For a paper to be included, the participants in a paper’s sample must have self-harmed at least once and undergone individual psychotherapeutic intervention. The studies had to have qualitative investigation, and to be written in (or translated into) English. All studies were appraised for their quality prior to the analysis.

Meta-ethnography is a method for combining data from qualitative research. The authors followed Noblit and Hare’s (1998) approach involving seven stages. This procedure allows for common concepts and themes across studies to be identified and considered in the review.

Results

Ten eligible papers, with a total sample of 104, were identified and used in the final synthesis. These papers considered a range of psychological therapies: DBT, counselling, psychodynamic interpersonal therapy (PIT), cognitive analytic therapy (CAT), emotional regulation therapy (ERT) and eclectic psychotherapeutic intervention. The vast majority of participants were female.

Four main themes (and nine subthemes) emerged from the analysis, each theme and subtheme had support from at least 6 papers.

Foundations of change

- Building up trust and feeling safe – participants required time and patience to feel safe, and they would withhold information or disengage if they did not feel safe.

- Relationship with change – therapy is of limited help for those who do not feel ready to confront their self-harm, adaptations based on tolerance are important.

Therapeutic relationship as a vehicle for change

- Validating environment – the importance of being understood and respected.

- Power and collaboration – client-led therapy is imperative to making progress.

Development through the therapeutic process

- Awareness and understanding – It is important to develop an awareness of what triggers precede self-harming.

- Moving beyond self-harm – participants described that they were unable to stop self-harming until they dealt with the issues that underlie the behaviour.

- Therapeutic techniques: a ‘band-aid’ approach – largely participants reported alternative strategies to be helpful, with a wide variety of specific therapeutic techniques being used. By exploring a range of strategies and allowing participants to be actively engaged in sessions, therapy gave them realistic alternatives to self-harming.

Therapy as life-changing

- Interpersonal change – reflective thinking about self-harm, and control over impulses and emotions, helped participants to better manage interpersonal exchanges and improved relationships.

- Intrapersonal change – successful therapy resulted in a strong sense of change for participants within themselves, being able to build an identity that endures without the need for self-harm.

Underlying all themes was the importance of recognising the person beyond the self-harm behaviour. Therapy needs to centre around the unique needs of the participants. Participants were consistent in their preference for self-harming behaviours to be accepted as an understandable way of coping with distress.

The techniques that were effective in therapy differed between participants, showing that therapy needs to be person-centred.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the alliance between client and therapist is important for effectively treating self-harm. Creating a “collaborative and accepting therapeutic space where individuals could feel safe” is important. Therapists should be utilising key clinical competencies while considering the unique individual needs and preferences of the client. When therapy is effective, the benefits for the patient span beyond the cessation of self-harming behaviour, with increased resilience and better management of interpersonal relationships.

Trust and acceptance are important values within the therapeutic context to support reflection on self-harm and ways to manage it.

Strengths and limitations

All themes and sub-themes presented by the authors contained evidence from at least six papers, and for most themes, evidence came from eight or nine papers. This suggests that the experiences of psychotherapy are consistent for participants, despite participating in different kinds of psychotherapy. By assessing a range of psychotherapies, Haw et al.’s advice can be used by practitioners specialising in different disciplines.

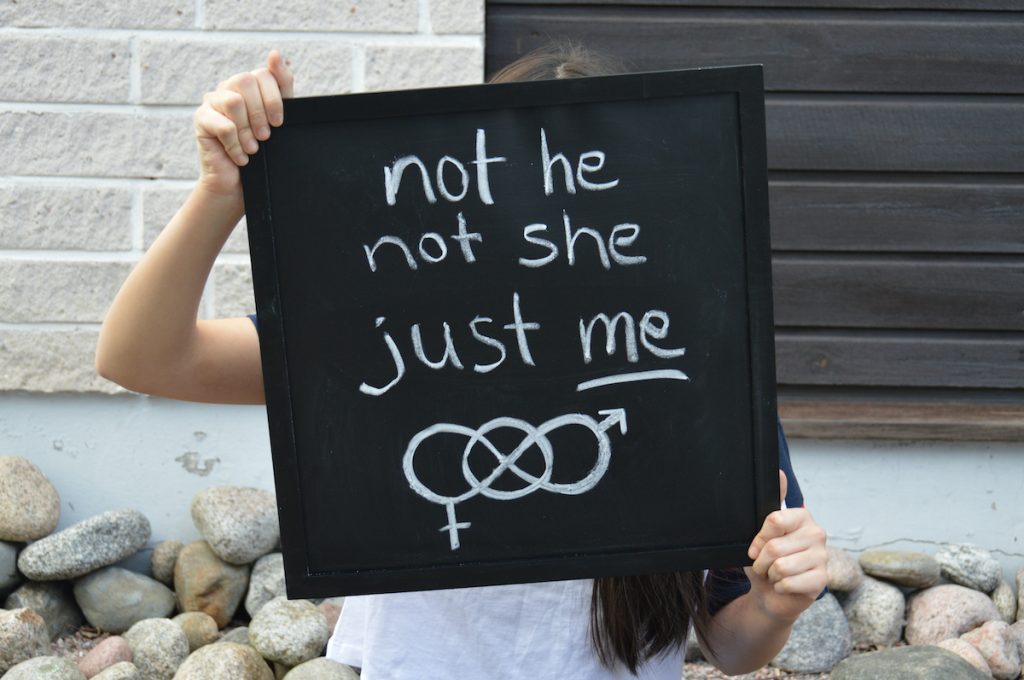

Of the 104 participants included in the review, 101 of them were female. While there are generally higher rates of self-harm in women, the effect size difference is only small (Bresin & Schoenleber, 2015). Six of the ten papers reviewed did not report the ethnicity of their participants, but the four that did report the majority of white samples. The participants’ experiences reviewed are limited, males and people from minority backgrounds who self-harm, may have different experiences of psychotherapy. In future qualitative analyses, the inclusion of underrepresented participants is important to ensure that considerations are made to fulfil the needs of the wider population. This also means that the recommendations of the paper may be inappropriate for non-white and/or non-female patients.

For obvious practical reasons, studies that were not written or translated into English were excluded from the analysis. The number of studies that were excluded on these grounds was not reported. Studies not in English may have provided a different perspective and may have resulted in a more diverse sample. This weakness may have contributed to the underrepresentation of minority groups in the final sample.

The collated sample in this review was overwhelmingly female. Do the findings apply to under-represented genders?

Implications for practice

The main take-home implication for practitioners is to focus on the individual needs of their patients. That may also be particularly important for CAMHS practitioners who work with vulnerable young people, given the elevated risk of self-harming and suicidal behaviours in this population. The authors found that perceived success in therapy was not related to a particular psychological strategy but through adaptation to the individual. Collaboration with the patient in determining what strategies and alternatives to self-harm are effective and empowered participants. This in turn leads to a more trusting therapeutic relationship. Practitioners should bear this in mind when treating service users who self-harm.

Trust between the client and the therapist is key to reducing self-harming. If service users do not yet trust their therapist, any pressure to try and stop self-harming behaviours will most likely be ineffective. Participants preferred for self-harming behaviours to be accepted as an understandable way of coping with pain and distress. Perceived success in therapy is unique, and not measured by self-harm reduction. Participants felt that they wanted to address the issues underlying their self-harming behaviours before tackling the behaviour itself.

Practitioners need to focus on building a therapeutic alliance and tackling the underlying and often systemic problems that may lead to self-harming behaviour before they start to encourage the cessation of self-harming behaviour.

Forming a therapeutic alliance is important prior to encouraging the cessation of self-harming behaviours.

Statement of interests

HW has a personal interest in treating self-harm, but is not involved in any research investigating the topic.

Links

Primary paper

Haw, R., Hartley, S., Trelfa, S., & Taylor, P. J. (2023). A systematic review and meta‐ethnography to explore people’s experiences of psychotherapy for self‐harm. British journal of clinical psychology, 62(2), 392-410.

Other references

Bresin, K., & Schoenleber, M. (2015). Gender differences in the prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury: A meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 38, 55-64. [abstract]

Hawton, K., Saunders, K., Topiwala, A., & Haw, C. (2013). Psychiatric disorders in patients presenting to hospital following self-harm: a systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 151(3), 821-830.

McManus, S., Gunnell, D., Cooper, C., Bebbington, P. E., Howard, L. M., Brugha, T., … & Appleby, L. (2019). Prevalence of non-suicidal self-harm and service contact in England, 2000–14: repeated cross-sectional surveys of the general population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(7), 573-581.

Murphy, E., Steeg, S., Cooper, J., Chang, R., Turpin, C., Guthrie, E., & Kapur, N. (2010). Assessment rates and compliance with assertive follow-up after self-harm: cohort study. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(2), 120-134. [abstract]

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies (PDF) (Vol. 11). Sage.

Selby, E. A., Bender, T. W., Gordon, K. H., Nock, M. K., & Joiner Jr, T. E. (2012). Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) disorder: a preliminary study [PDF]. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 3(2), 167.

Swannell, S. V., Martin, G. E., Page, A., Hasking, P., & St John, N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self‐injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta‐analysis and meta‐regression. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 44(3), 273-303. [abstract]

Witt, K. G., Hetrick, S. E., Rajaram, G., Hazell, P., Salisbury, T. L. T., Townsend, E., & Hawton, K. (2021). Psychosocial interventions for self‐harm in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (4). [abstract]

Photo credits

- Photo by Rupert Britton on Unsplash

- Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash