More than 804,000 people die by suicide globally each year (WHO, 2014) and the majority of these individuals are men; indeed in Great Britain, three quarters of those who died by suicide in 2016 were men (ONS, 2017). The most recent figures released by UK suicide prevention charity, Samaritans, showed that the highest suicide rate in the UK was among men aged 40-44 (Samaritans, 2017).

Recent years have seen much-needed media attention shone upon the issue of male suicide, highlighting the pressing need for us to be better at supporting men in crisis, so that they do not reach a point where they feel suicide is the only option. The evidence base for existing psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults is not encouraging, and even for interventions (CBT & DBT) which do indicate a positive effect on reducing self-harm repetition, the quality of the evidence is moderate to low and there is little to suggest particular benefits for men (Hawton et al., 2016).

Men are often identified as being more reluctant to seek help for mental health problems and suicidal thoughts than women (e.g. Biddle et al., 2004) and the question of ‘how can we get more men to access support?’ is frequently asked. To flip the script, potentially a better way of approaching the issue of increasing support and treatment uptake in men is to ask instead ‘how can we build treatments and services that men want to use?’

In a recent Evidence-Based Mental Health study, Mackie and colleagues (2017) use qualitative methods to elicit information regarding men’s experiences of receiving a blended therapy intervention, which combined face-to-face problem-solving therapy with an app.

Mackie et al’s (2017) study had two main objectives:

- To inform the development of a treatment manual, to be used in a large cluster-randomised trial of blended therapy

- To describe men’s experiences of receiving this therapy.

Men are often identified as being more reluctant to seek help for mental health problems and suicidal thoughts than women.

Methods

Blended therapy

Mackie and colleagues’ (2017) study used blended therapy, but what exactly is blended therapy? The term is used to describe treatment where some form of web-based therapy acts as a replacement for a portion of regular face-to-face therapy, or as a supplement to this (van der Vaart et al., 2014).

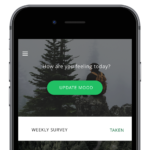

In the case of the current study, the blended therapy comprised six sessions of one-to-one, face-to-face problem-solving therapy delivered by a psychiatrist, and administered over the course of six to ten weeks. These face-to-face sessions were delivered in combination with a modified version of the smartphone app, ACHESS (Addiction Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System), which as the name suggests, was originally developed in the context of substance use addiction. As well as a BEACON button, which sends an alert to participants’ psychiatrists and reminds participants of their safety plan, there are four other main functions within the app:

- Gather: A list of individuals from their social network whom participants can contact for support.

- Connect: A messaging function through which participants can contact individuals from their social network list.

- Discover: Patient education resources in various forms, including web, audio and video, as well as self-generated content the user can upload themselves.

- Plan: ‘Implementation of agreed goals’ as outlined in the face-to-face problem-solving therapy sessions. Here, ‘high risk’ addresses can also be programmed in, so that if a participant gets close to such an address, this is detected by GPS and a warning message is sent to the participant.

A ‘Clinician Dashboard’ also provides a platform for app-users and their psychiatrists to have contact in-between sessions, and provides clinicians with an alert should the participant indicate elevated distress and suicidal ideation.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were seven adult men who presented with self-harm to the emergency department of a large urban hospital in Canada and who owned a smartphone. In the current study, the definition of self-harm is ‘non-fatal self-injury or self-poisoning irrespective of suicidal intent’ (NICE, 2004; 2011). Emergency room staff referred potential participants to a member of the research team, who then contacted them with further information regarding the study. Finally, potential participants were invited to a baseline appointment at the University campus where they completed informed consent and were familiarized with the app.

Up to six months following the end of face-to-face therapy sessions, semi-structured interviews were carried out with participants. Two independent coders then analysed the data using a ‘thematic grounded theory approach’. Neither of the coders had contact with the participants during the study. In addition to the semi-structured interview, participants also completed a Participant Exist Questionnaire, assessing user satisfaction with the app, and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), which assesses depression within the preceding two-week period.

This qualitative study explored the feasibility of blended therapy (face-to-face problem solving therapy with a psychiatrist plus a mobile phone app) for men who self-harm.

Results

Six of the seven men who received the intervention completed the semi-structured interview and engagement with the intervention was high: ‘85.7% of participants completed all follow-up appointments and 100% of participants completed five out of six sessions.’

Two main themes emerged from the coding: trust and connection.

Trust

Several participants highlighted that they were uncertain whether they could trust the BEACON button to work, as there were some technical issues and bugs because of the app being only in the beta phase. This led some participants to be hesitant about using the BEACON button in a crisis. Several participants indicated that the BEACON button helped them to begin using their safety plan and to remind them that ‘help is there’. In some cases though, this function also caused worry, and they were concerned about ‘accidentally triggering an emergency response.’ Some participants described the BEACON button as their ‘favourite thing about the study’, but also worried how well-resourced such a crisis service would be when the app was widely available:

Because there are different circumstances where you [might reach out], like, it’s not a 9-1-1 situation, but it’s also not a, like, wait six weeks for an appointment situation.

Connection

The theme of connection overlapped with that of trust and this centred around connection between the user, the app and the therapist. Personalisation was a key consideration for participants and many gave suggestions for how the app could be improved if it were more personalised to users, such as the patient education resources in ‘Discover’ being tailored to individuals’ specific mental health needs. Many users also found that residual features of the app’s originally intended use in sobriety maintenance, even though now adapted for the context of self-harm, limited identification and feelings of connection with the app. For one participant, this also brought back unwelcome memories of his experiences with alcoholism.

Overall, the majority (4/6) of participants reported their support expectations being met or exceeded by the problem-solving therapy, but only 2/6 reported that they would use ACHESS again. Participants found the relaxation and breathing exercises, as well as the therapist messaging, particularly useful features of the app. None of the participants re-presented to hospital with self-harm during the study period and whilst not the primary outcome of the study, mean PHQ-9 scores decreased from 18.3 (SD: 5.5) at baseline to 13.7 (SD: 10.0) at the final therapy session.

The clinician in the study reported some mixed feelings regarding the intervention, noting that the app was sometimes time-consuming and became an additional topic to be covered in sessions. Furthermore, the app did not wholly integrate with the face-to-face therapy, which may have limited the added value of the blended therapy approach in the current study. Conversely, the therapist also felt that the app increased feelings of patient-therapist connection and provided a useful repository of resources to which patients could be directed.

Personalisation was a key consideration for participants and many gave suggestions for how the app could be improved if it were more personalised to users.

Conclusions

The study concludes:

It is feasible to deliver blended therapy to a high-risk population, and it generated new ways to provide support in this group.

The primary aim of the study was to gauge user experiences with blended therapy in order to inform the development of a treatment manual for use in a full-scale RCT. Participants in the pilot study highlighted a number of both positives and negatives of the blended therapy approach, and the negatives were particularly in relation to the smartphone app. Trust in the technical reliability of the app and how well this would function in a crisis was a central issue raised by participants, as well as suggestions that greater personalisation of the app’s features would improve feelings of connection between the app, the patient, and the therapist. The study clinician also felt that the greater connection fostered by the app resulted in increased treatment adherence, although the app itself could sometimes prove time-consuming during sessions.

This pilot study concludes that it’s feasible to deliver blended therapy to a high-risk population like men who self-harm.

Strengths and limitations

The current study offers a valuable window into what individuals involved in a self-harm intervention actually experience. In many cases, patients’ experiences of an intervention are reduced to change scores on quantitative outcome scales, and there is little said about how participants feel about the intervention and its administration. That is not to say that change in quantitative measure of clinically relevant variables is not important, rather that it gives only part of the story. Qualitative research often gets short-shrift within the field of suicidology and this continues to be a highly topical issue (see Hjelmeland & Knizek, (2010) and Joiner (2011) for further discussion). Within the current study, qualitative data give us a richly detailed and critically important insight into patients’ experiences of interventions, and highlights key considerations for the development of future interventions, which an exclusively quantitative study design may otherwise have missed.

As acknowledged by the authors, the study is small and so the generalisablity of the findings is limited by there being only six participants who completed the interviews. Furthermore, all participants shared the same clinician, so the generalisability of the clinician’s perspective on delivering blended therapy, is also limited.

The study is a pilot, and thus an integral aspect of this is to refine elements of the study to then test further in the planned, full-scale RCT. A number of the drawbacks of the intervention reported by participants specifically relate to technical bugs within the app, such as residual features of its previous function as a sobriety tool. On the one hand I feel this is an excellent illustration of how user-unfriendliness of apps can become a dominant issue when evaluating an intervention involving an app. On the other hand, I feel that some of these issues, such as the appearance of sobriety messages, could perhaps have been foreseen before the pilot, in order to enable the pilot to yield more meaningful information regarding the acceptability of using an app per se, rather than how well this particular app was adapted from its original use. With system bugs being a pressing concern for participants, and thus emerging strongly within the interview data, it is possible that other useful information such as whether the app fulfilled its intended therapeutic function, may have been obscured.

App-based interventions for mental health are booming (Bakker, Kazantzis, Rickwood, & Rickard, 2016), yet are largely without a firm evidence-base (Anthes, 2016) and this is particularly the case for suicide-prevention apps (Larsen, Nicholas, & Christensen, 2016). Whilst not without its limitations, the current study makes an important contribution to the literature around our understanding of how individuals who self-harm experience a blended therapy intervention and what are the elements of an app that users and clinicians find most crucial.

App-based interventions for mental health are booming, yet are largely without a firm evidence-base and this is particularly the case for suicide-prevention apps.

Summary

This qualitative study by Mackie et al (2017) sought to examine the experiences and feasibility of blended therapy for men who self-harm. The therapy took the form of a smartphone app and face-to-face problem-solving therapy sessions. Trust and connection emerged as the main themes in the analysis, and participants described concerns with technical stability with the app, as well as speaking positively of the increased feeling of connection it fostered with their therapist.

The authors conclude that it is feasible to deliver blended therapy with men who self-harm, but technical soundness is a key element that must be addressed if such an intervention is to succeed.

Trust and connection emerged as the main themes in this qualitative study of blended therapy for men who self-harm.

Tweet chat

We are grateful to our friends at @WeMHNurses who hosted a tweet chat on this paper on Tuesday 28th November.

Conflict of interest

Olivia Kirtley was one of the original peer-reviewers for this manuscript for the Evidence-Based Mental Health journal.

Links

Primary paper

Mackie, C., Dunn, N., MacLean, S., Testa, V., Heisel, M., & Hatcher, S. (2017). A qualitative study of a blended therapy using problem solving therapy with a customised smartphone app in men who present to hospital with intentional self-harm. Evidence-Based Mental Health, ebmental–2017.

Other references

Anthes, E. (2016). Pocket Psychiatry. Nature, 532, 20–23.

Bakker, D., Kazantzis, N., Rickwood, D., & Rickard, N. (2016). Mental Health Smartphone Apps: Review and Evidence-Based Recommendations for Future Developments. JMIR Mental Health, 3(1), e7. http://doi.org/10.2196/mental.4984

Biddle, L., Gunnell, D., Sharp, D., & Donovan, J. L. (2004). Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross-sectional survey. The British Journal of General Practice: The Journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners, 54(501), 248–253.

Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Hazell P, Townsend E, van Heeringen K. (2016). Psychosocial interventions for self-harm in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD012189. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012189.

Hjelmeland, H., & Knizek, B. L. (2010). Why we need qualitative research in suicidology. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(1), 74–80.

Joiner Jr., T. E. (2011). Editorial: Scientific Rigor as the Guiding Heuristic for SLTB’s Editorial Stance. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(5), 471–473. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2011.00056.x

Larsen, M. E., Nicholas, J., & Christensen, H. (2016). A systematic assessment of smartphone tools for suicide prevention. PLoS ONE, 11(4), e0152285. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0152285

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2004). Self-harm. The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. Retrieved from http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg16

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2011). Self-harm: longer term management. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg133

Office for National Statistics. (2017). Suicides in Great Britain: 2016 registrations.

Scowcroft, E. (2017). Samaritans Suicide Statistics Report 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.samaritans.org/about-us/our-research/facts-and-figures-about-suicide

van der Vaart, R., Witting, M., Riper, H., Kooistra, L., Bohlmeijer, E. T., & van Gemert-Pijnen, L. J. E. W. C. (2014). Blending online therapy into regular face-to-face therapy for depression: content, ratio and preconditions according to patients and therapists using a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 355. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-014-0355-z

World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/

Photo credits

- Photo by Matthew Hamilton on Unsplash

- Photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

- Jose Hernandez CC BY 2.0