Although efficacy may be less than hoped and side effects more than hoped, antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment for people diagnosed with schizophrenia. By contrast, psychological interventions such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) are invariably offered as an adjunctive (additional) intervention.

Recently however, some argue that psychological interventions are just as efficacious as antipsychotic medication. For example, both editions of the British Psychological Society document Understanding Psychosis and Schizophrenia boldly claim that “…there is general consensus that on average, people gain around as much benefit from CBT as they do from taking psychiatric medication”. Elf blogs in 2014 and 2017 have provided critiques of the Understanding Psychosis reports.

Some have even extended this stance to assert that psychological interventions be offered as an alternative to medication (e.g. Morrison, 2019). Given the lack of head-to-head comparisons of antipsychotics and psychological therapy, such radical claims rely upon simple comparisons of effect sizes that emerge from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of drugs and psychotherapy. But are drug and psychotherapy trials comparable in this simple, transparent manner?

The current paper by Bighelli et al casts a revealing light upon how RCTs of antipsychotics and psychological interventions match-up. Are they comparable in terms of: trial methodologies? patients enrolled? risk of bias and potential conflicts of interest? Or are they so different that we simply cannot draw any conclusions about comparable efficacy…yet?

Some experts assert that psychological interventions should be offered as an alternative to medication for people diagnosed with schizophrenia, but do we have the evidence to support this?

Methods

Bighelli and colleagues compared RCTs from their own earlier systematic reviews of pharmacological (Leucht et al, 2017) and psychological (Bighelli et al, 2019) interventions for schizophrenia. These comprehensive, up-to-date reviews both focussed on positive symptom reduction as the primary outcome.

Results

The current analysis therefore compared 80 trials of antipsychotics (18,271 participants) with 53 trials (4,068 participants) assessing various psychotherapies (CBT, metacognitive training, mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy, experience-focused, counselling, hallucination-focused integrative treatment, and AVATAR therapy). The main findings were:

Patient characteristics and study characteristics

- Patients enrolled into antipsychotic drug trials were more severely-ill at baseline as rated on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS: 93.97 vs 71.72), had a longer history of illness (14 vs 12.37 years), and were older (38.95 vs 37.42 years) than those enrolled into psychotherapy studies

- More than three-quarters (86%) of drug trials recruited only inpatients, whereas only one-quarter (25.64%) of psychotherapy studies did so

- Drug trials had much larger samples than psychotherapy trials (313.53 vs 76.35 patients), used many more study centres (36.69 vs 3.33) and often across multiple countries. Indeed, psychotherapy trials were conducted mainly in only one country, with around half solely in the UK

- Psychotherapy trials had an average duration that was 3 times longer than drug trials (19 vs 6 weeks)

- Control conditions differed markedly. While all antipsychotic trials used pill placebo, psychotherapy employed various control groups e.g. other psychological interventions not focused on the treatment of positive symptoms (20.8% of studies), inactive controls (interventions intended to control for nonspecific aspects of the therapy: 17%), treatment as usual (54.7%) and wait-list (13.2%)

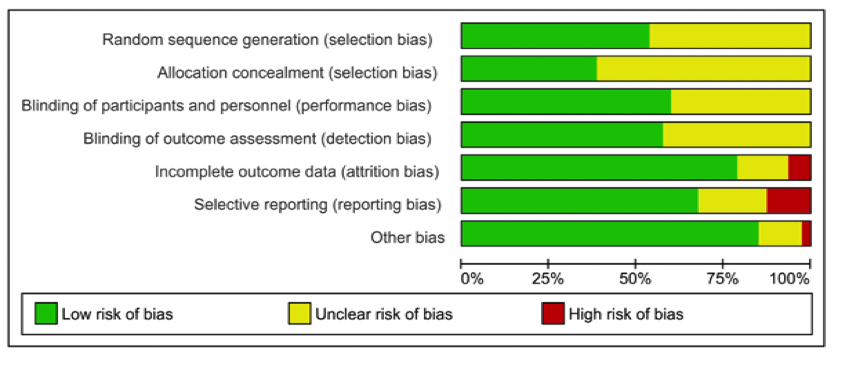

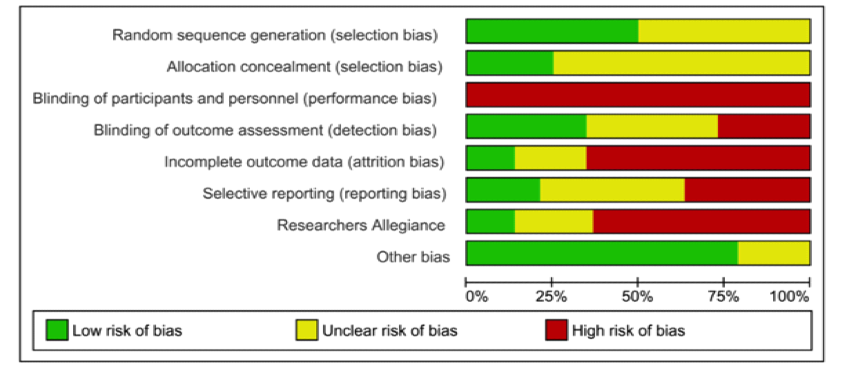

Risk of bias

Risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. This revealed that none of the risks were greater than 25% in drug studies, but 5 of the 8 areas of possible bias were significantly greater in psychotherapy trials.

Risk of bias: drug trials

Risk of bias: psychotherapy trials

- While all antipsychotic trials were double-blind, participants receiving psychotherapy cannot be blind to the intervention. At best then psychotherapy trials can have blind outcome assessment. While 100% of drug studies employed blind outcome assessment, one in four (25.92%) psychotherapy trials failed to do so.

- Incomplete data resulting from patient drop-out is a major issue in trials. One response is to use intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses, in which all patients are compared on their final results regardless of whether they had dropped-out of the study. Almost two-thirds (64%) of psychotherapy trials, but only 6.25% of antipsychotic trials were at high risk of bias because of incomplete outcome data and not having applied ITT analysis, or other strategies to account for missing data

- Psychotherapy trials were more frequently judged at high risk of bias for selective outcome reporting when compared to drug trials (35.19% vs 12.5%).

- The sponsorship of drug trials by pharmaceutical companies is a well-documented potential conflict of interest. The comparison for psychological interventions was researcher allegiance – where, for example, trial researchers were also involved in developing the intervention. On these measures, Bighelli et al found that rates of conflict of interest were high for both and did not differ significantly between drug and psychological interventions (76.92% vs 66.04%)

- Being an entry requirement for both original meta-analyses, no studies were at high risk of bias for randomisation or allocation concealment.

The key take-home message from this paper is that trials examining the efficacy of antipsychotics and psychotherapies for schizophrenia differ in key aspects of their design, their relative risks of bias and the characteristics of the patients recruited.

Conclusions

…pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy in schizophrenia are not intended as alternative treatments but are offered to different patients or at a different phase of the illness, as made clear by our results.

The key take-home message from this paper is that trials examining the efficacy of antipsychotics and psychotherapies for schizophrenia differ in key aspects of their design, their relative risks of bias and the characteristics of the patients recruited.

In each comparison where differences occur, however, they seem likely to inflate effect sizes for psychotherapy. Though longer in duration, psychotherapy trials samples are about a quarter of the size of that in drug trials and recruited from far fewer study centres. It is worth noting that trial length, the number of participants and how trials deal with drop-out are likely to interact. It seems feasible that longer psychotherapy trials might induce greater drop-out, impacting already smaller (underpowered) trials, which may then be compounded by the failure to use ITT analysis. These factors, alongside the lack of blind outcome assessment in 1 in 4 psychotherapy trials and the use of controls such as wait-list – all converge on potentially inflating and producing unreliable positive outcomes in psychotherapy trials. A similar picture emerges if we look at differences in the characteristics of patients recruited. Most importantly, drug studies enrolled more severely ill patients, who tended more often to be in-patients with a longer duration of illness. Such patients are precisely those who may well be less responsive to intervention (Rabinowitz et al, 2014).

Concerns over drug sponsorship of pharmacology trials are well-documented. Conflicts of interest, however, are not always financial and Bighelli and colleagues identify high levels of researcher allegiance in psychotherapy trials. Researchers who assess the efficacy of their own psychological interventions undoubtedly have a vested interest in reporting better results (which may be compounded by their unblinded assessment of outcomes). Indeed, researcher allegiance may inflate effect sizes in trials of psychotherapy for schizophrenia (Turner et al 2014).

Currently, psychotherapy trials rarely report researcher allegiance as a potential conflict, but it should be required in future trials and useful for meta-analyses, which can then report on the extent of influence.

One undeniable implication of this study is that RCTs of psychological interventions need to up-their-game and this is readily achievable in several areas. They could ensure blind assessment of outcomes, increase sample size to be sufficiently powered, adequately deal with drop-out, choose appropriate control groups, pre-register protocols to avoid selective reporting and declare any researcher allegiance as a potential conflict of interest.

One undeniable implication of this study is that RCTs of psychological interventions need to up-their-game and this is readily achievable in several areas.

Strengths and limitations

The systematic reviews of both antipsychotics and psychological interventions were conducted by the same team and so, are methodologically consistent regarding searching, data extraction, study appraisal and so on. Both reviews followed PRISMA guidelines, included published and unpublished trial data and had pre-registered protocols on the PROSPERO website (registration numbers CRD42013003342 and CRD42017067795).

Implications for practice

One clear implication of this elegant review is that drug and psychotherapy trials are so radically different that comparing their effect sizes is overly simplistic and unquestionably misleading. How should we answer the question… “Should people with psychosis be supported in choosing cognitive therapy as an alternative to antipsychotic medication?”

The current answer can only be that comparisons of the outcomes in drug versus psychotherapy trials are likely to be extremely misleading given the huge differences in trial methodology, types of patients recruited and risk of bias across the two types of trial. In general, most of these differences would likely favour a spurious inflation of psychotherapy effect sizes (and possibly also a reduction of psychopharmacology effect sizes).

One clear implication of this elegant review is that drug and psychotherapy trials are so radically different that comparing their effect sizes is overly simplistic and unquestionably misleading.

Conflicts of interest

Keith Laws has published several meta-analyses and reviews examining the efficacy of CBT for schizophrenia.

Links

Primary paper

Bighelli I, Leucht C, Huhn M, Reitmeir C, Schwermann F, Wallis S, Davis JM, Leucht S. (2019) Are Randomized Controlled Trials on Pharmacotherapy and Psychotherapy for Positive Symptoms of Schizophrenia Comparable? A Systematic Review of Patient and Study Characteristics, Schizophrenia Bulletin, sbz090, https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbz090

Other references

Bighelli I, Salanti G, Huhn M, et al. Psychological interventions to reduce positive symptoms in schizophrenia: systematic review and network meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):316–329

Bighelli, I., Huhn, M., Schneider-Thoma, J., Krause, M., Reitmeir, C., Wallis, S., … & Leucht, S. (2018). Response rates in patients with schizophrenia and positive symptoms receiving cognitive behavioural therapy: a systematic review and single-group meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 380.

Leucht S, Leucht C, Huhn M, et al. Sixty years of placebo controlled antipsychotic drug trials in acute schizophrenia: systematic review, Bayesian meta-analysis, and meta-regression of efficacy predictors. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):927–942.

Morrison, A. P. (2019). Should people with psychosis be supported in choosing cognitive therapy as an alternative to antipsychotic medication: A commentary on current evidence. Schizophrenia Research, 203, 94-98.

Rabinowitz J, Werbeloff N, Caers I, et al. Determinants of antipsychotic response in schizophrenia: implications for practice and future clinical trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(4):e308–e316.

Turner, D. T., van der Gaag, M., Karyotaki, E., & Cuijpers, P. (2014). Psychological interventions for psychosis: a meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(5), 523-538.

I did a similar exercise comparing two Cochrane reviews on using drugs versus aromatherapy for agitation in dementia. https://drive.google.com/open?id=1O-CH42ZfCLp4uOmdDwcFr3kMtdhvpFOO Similar conclusion. Researcher allegiance is a problem in all trials – whether of drugs or non-drug therapies. Equipoise seems to be dispensable when it is the most important factor in designing a good trial of an intervention. You are supposed to design a trial to try and prove the hypothesis (usually that something works) wrong.

Interesting & helpful