We all make decisions on a daily basis. However, severe mental health disorders are known to interfere with decision-making processes. The negative assumption is that people with chronic mental illnesses, particularly schizophrenia, do not possess the capacity to make decisions. But what actually is capacity, and is this pessimistic presumption justified?

Capacity has been defined as “an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions.” – Sahil Munjal, MD.

Clinicians have differentiated between decision-making capacity for treatment (DMC-T) and decision-making capacity for research (DMC-R). This is helpful, as it enables an understanding of capacity specific to different contexts rather than a ‘you either have it or you don’t’ approach. The former refers to the ability to provide informed consent about personal treatment decisions, and the latter refers to the ability to consent to participation in research such as clinical trials.

It is often the case that some people with schizophrenia lack capacity to make decisions about their treatment. This is largely due to their impairment in cognitive functioning rather than the severity of their psychotic symptoms. What is less understood, however, is whether patients with chronic schizophrenia have sufficient ability to make decisions about consenting to research.

After all, this population is often excluded from research studies, yet the reasoning behind their exclusion seems to be unjust. A diagnosis of schizophrenia should not automatically render the individual as incapable of making decisions about engaging in research. This only fuels the stigmatisation of the disorder.

A recent study published by Spencer and colleagues (2018) has investigated exactly this by asking the question: can inpatients with schizophrenia retain their capacity to make decisions about participating in research?

We perpetuate stigma if we presume that all people with schizophrenia cannot make informed decisions.

Methods

Researchers conducted a cross-sectional study in eight wards in the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

The study recruited 84 people with a diagnosis of non-affective psychotic disorders (defined by ICD-10) who were admitted for the purpose of assessment or treatment of psychotic symptoms. They were approached as soon as possible from 24 hours of admission.

Exclusion criteria

- Bipolar affective disorder or related affective psychoses

- Current intoxication

- Previous participation in a BioResource study.

Measures of Decision Making Capacity

Researchers used the NIHR BioResource as the ‘parent study’ – the study was explained to participants in order to assess their decision-making capacity for research consent (but not for treatment).

The NIHR BioResource is a non-therapeutic study which collects biological samples.

A semi-structured interview was conducted using the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool – Clinical Research. This measures decision-making capacity for research participation based on four factors:

- Understanding of the nature and procedures of research

- Appreciation of the effects of participation on their own situation

- Reasoning for participation

- Ability to communicate their choice.

The MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool – Treatment was used to assess participants’ decision-making capacity for treatment and admission to hospital. It has a similar four-factor approach.

Other measures

Participants also underwent a series of other assessments on symptoms of psychosis, insight, severity of illness, mood-related symptoms, and cognitive impairment. For example:

- The Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (PANSS) was used to measure positive symptoms (e.g. hallucinations, delusions) and negative symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety) of schizophrenia

- Neurocognitive Assessment Battery – developed by the researchers to assess verbal and working memory deficits.

Results

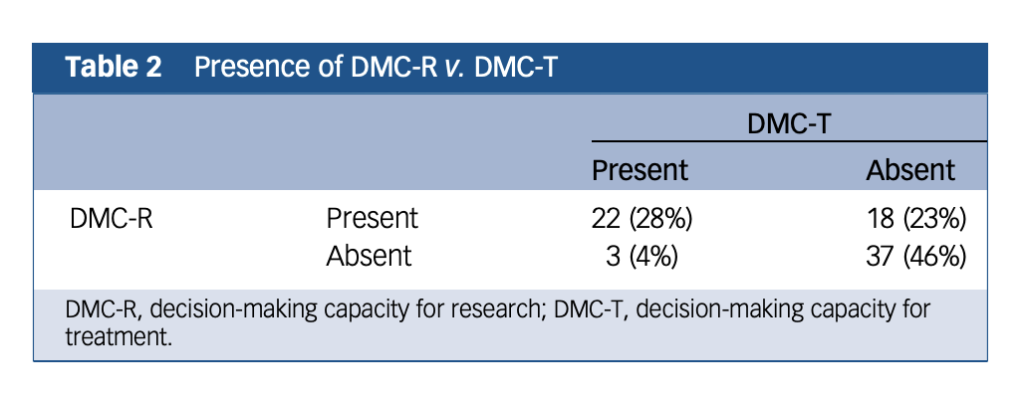

In the sample of 80 participants in total, half of them had DMC-R, while only one-third had DMC-T. The table below shows how DMC-R is different from DMC-T in terms of the retainment of DMC-R in a larger proportion of the sample:

“Table 2 shows the distribution of people having DMC-R v. DMC-T. Although in most cases participants either lacked or had both DMC-R and DMC-T (n = 59, 74%), there were dissociations: 23% (n = 18) had DMC-R but lacked DMC-T, and 4% (n = 3) lacked DMC-R but had DMC-T.”

The varying impacts of different symptoms on DMC-R and DMC-T also display them as two separate abilities. Out of all core symptoms of psychosis, only delusions had an impact on both DMC-R and DMC-T.

Insight & DMC-T

Lack of insight had the strongest link to lacking DMC-T. The reduced meta-cognitive ability (the ability to understand one’s own situation) in participants who lacked insight, caused difficulties appreciating the effects of treatment on their condition. This makes participation in treatment-related decisions less justifiable in general.

Thought Disorder & Understanding (DMC-R)

Thought disorder had the largest association with lacking DMC-R. Participants with thought disorder lacked DMC-R but retained DMC-T. The lack of DMC-R was mainly due to an absence of understanding of the research.

Thought disorder leads to poor understanding of new information about research and limits patients’ ability to make informed decisions for research.

In addition, demographic factors such as age, gender, ethnicity, previous involvement in research, and current employment, did not have effects on either DMC-R or DMC-T. The only exception was that greater years of education was associated with having DMC-R.

Thought disorder was most associated with lacking DMC-R, whereas lack of insight was most associated with lacking DMC-T.

Conclusions

The authors concluded:

We have shown that even when severely unwell, people with schizophrenia in in-patient settings retain DMC-R despite lacking DMC-T. Different symptoms have different effects on decision-making abilities for different decisions.

and

We should not view in-patient psychiatric settings as a research ‘no-go area’ and, where appropriate, should recruit in these settings.

Overall, this study addresses an important gap in the literature and a fundamental issue; it is encouraging to know that in-patient populations can and should be recruited into research studies.

This study opens the door for researchers to recruit people who are severely unwell into research studies.

Strengths

This is a very novel study; DMC-R is a neglected field of research with many studies focusing solely on DMC-T. The crucial point to take away from this study is that decision-making capacity varies across context.

- Patients with severe schizophrenia can retain DMC-R and this could encourage researchers to recruit this population into their studies. This will allow us to make more accurate generalisations (e.g., in clinical trials for a new treatment)

- The authors recruited a very under-researched sample (even those who were detained in hospital). This is helpful because this population is repeatedly excluded from research. This study emphasises that detainment does not equal incapacity to consent.

Limitations

However, the study is not without its flaws. The researchers do acknowledge that their study lacked power due to incomplete data from participants. To compensate for this, they restricted the analysis of PANSS and neurocognitive items for cases where there was full data. Additionally:

- The sample size was exceptionally small (N=80), and over 70% of participants did not complete the neurocognitive assessment. For the restricted analysis, researchers selected a range of PANSS items and neurocognitive items that had the most data. However, it was unclear if the selection of items was well founded, without being affected by any subjective judgement or bias from researchers.

- Cross-sectional design only gives us a snapshot of the patient at one time: we do not know if factors could change their ability to consent over time. For example, it is unclear what procedure should be followed in a longitudinal design if someone had capacity at the beginning but suddenly lacks capacity throughout.

- Bias: The assessments used took over 90 minutes to complete. The authors did acknowledge that this is a long time for such severely unwell participants. This led to a significant amount of missing data and leaves the study open to response bias; those who completed all of the assessments may have had less severe symptoms relative to those who did not complete them all.

It’s possible that this study suffers from response bias, whereby those who completed all of the assessments may have had less severe symptoms relative to those who did not complete them all.

Implications for practice

Schizophrenia is a chronic and severe mental disorder that is very misunderstood. Hence, clinical research into schizophrenia has become a great priority. Encouragingly, this study has revealed a dissociation between decision-making capacity for treatment and that for research. By including this neglected population in research, we can obtain a better understanding of the causes, risk factors and optimal treatments for schizophrenia.

On the flip side, perhaps we shouldn’t get too carried away with these findings and use them to inform research practice just yet. Informed consent is of prime importance when enrolling vulnerable individuals into research studies due to the significant risk involved. This study suffered from a few methodological limitations which restricts our ability to have full confidence in the authors’ conclusions. The next step would be to replicate this study across a variety of research and treatment settings using a larger sample size.

Future research may also consider focusing on fewer measures and reduce the assessment time to avoid high withdrawal rates. Besides, educational interventions could be developed to improve patients’ understanding of the purposes and procedures of research (Carpenter et al., 2000). Perhaps it is not yet the time to decide whether inpatients with schizophrenia are capable to make decisions for research, but it is the time that researchers used their best efforts to include these patients in research by challenging the assumption that schizophrenia automatically equals incapacity.

It’s time for researchers to challenge the assumption that schizophrenia automatically equals incapacity.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Georgia Penska @georgia_penska, Natalie Wong – @nat2w, Dylan Peters – @dylan_peters1, Taarika Chugh – @taarikac, Vicky Bamber – @vbambr, Noor Hassan – @Noor0396, Dawn Wong – @dawnwongyh, Vanessa Daccach – @vanessadaccach, Robyn Feldman – @robynfeldman1.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Spencer BWJ, Gergel T, Hotopf M, Owen GS. (2018) Unwell in hospital but not incapable: cross-sectional study on the association of decision-making capacity for treatment and research in in-patients with schizophrenia and related psychoses. British Journal of Psychiatry, 213 (2), 484-489. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.85

Other references

Carpenter, W. T., Gold, J. M., Lahti, A. C., Queern, C. A., Conley, R. R., Bartko, J. J., … & Appelbaum, P. S. (2000). Decisional capacity for informed consent in schizophrenia research. Archives of general Psychiatry, 57(6), 533-538.

Photo credits

- Photo by Gage Walker on Unsplash

- Morning Theft CC BY 2.0

- Photo by Fernando Paz on Unsplash

- Photo by Jan Tinneberg on Unsplash

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Johnny Jet CC BY 2.0