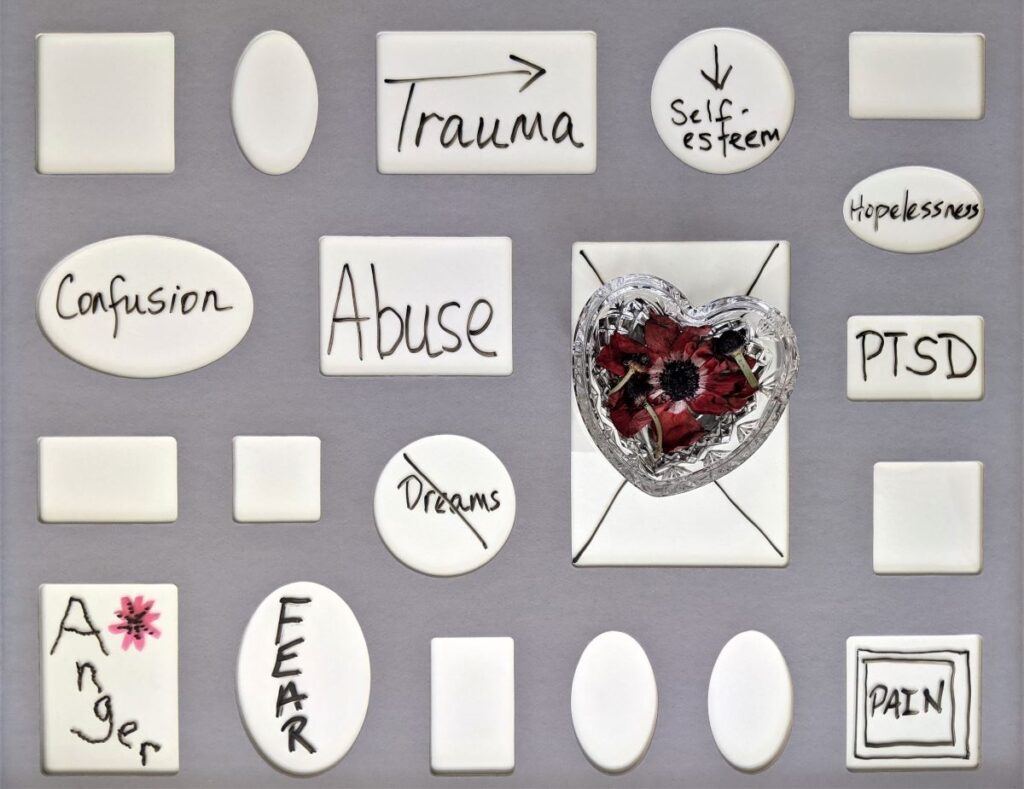

Psychological trauma is widespread across society, with over 70% of the general population having been exposed to one or more traumatic events (Benjet et al., 2016; Knipscheer et al., 2020). A large body of research has demonstrated a strong link between trauma and mental health problems, and it has been identified that a high proportion of people who use mental health services have experienced traumatic events, including childhood adversity, and physical and sexual abuse (Anderson et al., 2016; Mauritz et al., 2013; Phipps et al., 2019). In response, inquiries and reports have increasingly indicated an urgent need for mental health services to become trauma-informed (Bloom, 2006; Elliott et al., 2005; Sweeney et al., 2016).

Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) is an approach to care based on an awareness of the high prevalence of trauma, the effects of traumatic experiences, and the potential for trauma or traumatisation to occur within care (Harris & Fallot, 2001). The basic premise of TIC is a shift in the therapeutic approach from asking ‘What is wrong with you?’ to considering ‘What happened to you?’ (Bloom, 2006).

Investigations of the effectiveness of TIC are in their early stages, however, with preliminary evidence suggesting that TIC has the potential to reduce the effects of traumatic experiences, aid recovery from mental illness and enhance the quality of patient care (Lietz et al., 2014; Marsac et al., 2016; Muskett, 2014). However, the approach is usually referred to conceptually, which leads to difficulties in its translation into practice and for many mental health services, TIC has proven difficult to implement (Hodgdon et al., 2013; K Hopper et al., 2010; Muskett, 2014; Yatchmenoff et al., 2017). Moreover, experiences of consumers differ across contexts and settings and how TIC should be delivered within mental health services is not well documented.

That is why in a recent Australian study, Isobel and colleagues (2020) aimed to better understand the practical potential of this approach and explored the perspectives of mental health consumers and their carers in relation to the question ‘what would a trauma-informed mental health service look like?’

Due to a high prevalence of trauma among people who access mental health services, trauma-informed care has been gaining traction. However, the core principles of this approach are yet to be translated into practice.

Methods

This study (Isobel et al, 2020) was a part of a larger project that used an experience-based co-design (EBCD) methodology – a collaborative approach to improving health services which enables consumers, carers, and staff of all levels to co-design better services (Larkin et al., 2015). The project was led by an advisory group with professional and/or lived experience of mental health services and knowledge of TIC.

The researchers conducted focus groups with consumers (n=10) and their carers (n=10) from across New South Wales (NSW), Australia. The 1-hour long focus groups were held separately for consumers and carers and were led face-to-face by an experienced mental health clinician and a consumer-researcher with lived experience of mental illness and trauma. Notably, the participants were not screened for the specific nature and extent of their mental health issues and their trauma history and were asked not to share that information with the group.

Questions were developed by the advisory group and based on the principles of TIC and included asking participants to recall times when they felt safe in care, when they felt included in care, when and how their past experiences were incorporated into their current care, and what their hopes were for the future of mental health services.

The discussions were then transcribed and analysed by the advisory group, using thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Results

The following overarching themes were identified:

1. Being aware of trauma

To be trauma-informed, all clinicians should have awareness of trauma and, without necessarily dwelling too deep, they should be willing to talk to people about their past experiences and link them to present behaviours.

2. Collaborating in care

Active inclusion in care processes was identified as essential to aid recovery, reduce harm occurring in care, and to address individualised care needs. Consumers and carers would be involved in care planning and decision making. For instance, consumers would have a say in aspects of care such as the gender of people providing direct care, medication prescribed, and the setting in which care is delivered.

3. Building trust

Participants further explained that collaboration requires trust. Ideally, staff would provide clear and transparent explanations around how and why decisions are made, and they would listen to people about their care experiences, both positive and negative, and would meaningfully incorporate them into care. Furthermore, to help with existing trust issues, participants said it was necessary for mental health services to employ people with lived experience at all levels.

4. Creating safety

Trauma-informed mental health services should focus on minimising traumatisation and re-traumatisation occurring within care. Safety would be expressed through interpersonal interactions, as well as through physical environments. This could be achieved through clear communication about what is happening and involvement in decision-making. Importantly, a trauma-informed service would minimise overt displays of power and seek to equalise power differentials within services by restoring a sense of humanity to consumers’ experiences.

5. Delivering a diversity of models

Participants agreed that trauma-informed mental health services would offer a diversity of models of care and treatment that reflected the unique needs of each consumer. They believed there should be a decreased focus on diagnosis and pharmacological therapies. Rather, consumers would have access to a diversity of treatment options, including psychological therapies to gain skills to cope.

6. Staff practising with consistency and continuity

Enhanced communication, sensitivity and transparency would minimise confusion and fear that often accompany transitions between care. Importantly, while it would not always be possible to have continuity of individual clinicians, interactions with all mental health staff across services would be consistently non-judgmental.

Participants identified that trauma-informed care requires increased awareness of trauma amongst mental health staff, opportunities to collaborate in care, active efforts by services to build trust and create safety, the provision of a diversity of models and consistency and continuity of care.

Conclusions

The participants in this study identified several specific strategies to enhance trauma-informed care (TIC) and improve overall mental health care experiences. They emphasised concepts related to human connectedness as vital and acknowledged the multi-dimensional factors that challenge these concepts in mental health settings.

This study provides suggestions for specific strategies to enhance trauma-informed care and highlights the importance of mental health services to work towards becoming trauma-informed.

Strengths and limitations

This is a very important, novel, and thoughtfully conducted study.

Efforts towards trauma-informed care (TIC) in any setting require engagement with those who receive care – the researchers did a great job by involving consumers of mental health care at all stages of the project. Notably, the focus groups were co-led by a consumer-researcher with lived experience of mental illness and trauma and a mental health clinician. This dual facilitation assisted in the provision of safety and likely increased trustworthiness among participants. Moreover, consumer and carer focus groups were held separately in acknowledgement of the diversity of experiences for each group. It is apparent from such well-thought-through methodological decision-making, that the study’s design itself was trauma-informed.

However, the study also had a few limitations, some of which were observed by the researchers themselves. For example, the development of TIC requires inputs from consumers and carers both together as well as individually, as their experiences are not always shared. However, this study presented the perspectives of consumers and carers together, automatically consolidating their perspectives, which may be misleading and risk assuming a shared agenda and needs. However, the authors reported a detailed finding from each group, which can be accessed through the wider project report (NSW ACI, 2020).

Next, as the authors also noted, the participants were approached through community organisations in metropolitan areas of New South Wales in Australia. This means that those who do not engage with such organisations, or who live in other areas with limited access to these resources, were unlikely to participate. The authors also noted that this study may not have captured perspectives of people who do not identify as “consumer or “carer”, but still access mental health services. Also, because healthcare systems differ markedly across countries, the findings would probably not be exactly replicated elsewhere – especially in low-income countries with poorer healthcare systems.

It is also important to note that the nature and extent of people’s mental health issues, and their trauma history, were not screened for. While TIC can be universal for everyone – no matter if they have experienced trauma or not – some mental health diagnoses and some types of traumatic experiences are associated with different needs in care, as well as with different attitudes from healthcare staff.

Furthermore, some people, including people of colour and members of the LGBTQ+ community, are more likely to experience trauma and are consistently overrepresented in acute mental health care, but receive the most negative and adversarial responses which are known to cause iatrogenic harm (Mohan et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 2010). However, participants’ sociodemographic information was not provided in this study, so we don’t know if people of colour or members of the LGBTQ+ community were included in the research.

Such differences and unique personal experiences of each participant might have been reflected in their perspectives regarding the premise and implementation of TIC. It would be interesting for future research to explore whether and how people from different backgrounds and with specific mental health diagnoses and with specific types of trauma experience current care, and how TIC might be applicable to different mental health issues.

This study demonstrates methodological rigour and thoughtfulness by involving consumers of mental health care at all stages of the project.

Implications for practice

This study undoubtedly contributes novel and useful data for clinicians and services that would like to become trauma-informed. Because trauma-informed care (TIC) is a universal approach that is suitable for everyone, the findings have implications for the implementation of trauma-informed care across several settings.

The guidance provided by this study highlights that clinicians should work to ensure they have awareness of trauma, are able to provide opportunities to collaborate, practice with consistency and continuity, build trust and prioritise safety for all service users, alongside offering access to a diversity of models of care. In this way, services can greatly improve the translation of the principles of TIC into practice and improve experiences of all people who access services.

Staff training and education in TIC is strongly encouraged, as are processes of consumer feedback, structures to support consumer and carer collaboration, well–supported peer roles, non-pharmacological therapies, and continuity of care across settings.

Clinicians should work to ensure they have awareness of trauma and the skills needed to build trust with all service users.

Links

Primary paper

Isobel, S., Wilson, A., Gill, K., & Howe, D. (2021). ‘What would a trauma-informed mental health service look like?’ Perspectives of people who access services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 495-505.

Isobel, S., Wilson, A., Gill, K., Schelling, K., & Howe, D. (2021). What is needed for Trauma Informed Mental Health Services in Australia? Perspectives of clinicians and managers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 72-82.

Other references

Anderson, F., Howard, L., Dean, K., Moran, P., & Khalifeh, H. (2016). Childhood maltreatment and adulthood domestic and sexual violence victimisation among people with severe mental illness. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 51(7), 961-970.

Benjet, C., Bromet, E., Karam, E. G., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Ruscio, A. M., . . . Hill, E. (2016). The epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychological medicine, 46(2), 327-343.

Bloom, S. L. (2006). Human service systems and organizational stress. Retrieved July, 14, 2018.

Elliott, D. E., Bjelajac, P., Fallot, R. D., Markoff, L. S., & Reed, B. G. (2005). Trauma‐informed or trauma‐denied: Principles and implementation of trauma‐informed services for women. Journal of community psychology, 33(4), 461-477.

Harris, M., & Fallot, R. D. (2001). Envisioning a trauma‐informed service system: a vital paradigm shift. New directions for mental health services, 2001(89), 3-22.

Hodgdon, H. B., Kinniburgh, K., Gabowitz, D., Blaustein, M. E., & Spinazzola, J. (2013). Development and implementation of trauma-informed programming in youth residential treatment centers using the ARC framework. Journal of Family Violence, 28(7), 679-692.

K Hopper, E., L Bassuk, E., & Olivet, J. (2010). Shelter from the storm: Trauma-informed care in homelessness services settings. The open health services and policy journal, 3(1).

Knipscheer, J., Sleijpen, M., Frank, L., de Graaf, R., Kleber, R., Ten Have, M., & Dückers, M. (2020). Prevalence of potentially traumatic events, other life events and subsequent reactions indicative for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Netherlands: a general population study based on the trauma screening questionnaire. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(5), 1725.

Lietz, C. A., Lacasse, J. R., & Cheung, J. R. (2014). A case study approach to mental health recovery: Understanding the importance of trauma-informed care. Ethical Human Psychology and Psychiatry, 16(3), 167-182.

Marsac, M. L., Kassam-Adams, N., Hildenbrand, A. K., Nicholls, E., Winston, F. K., Leff, S. S., & Fein, J. (2016). Implementing a trauma-informed approach in pediatric health care networks. JAMA pediatrics, 170(1), 70-77.

Mauritz, M. W., Goossens, P. J. J., Draijer, N., & Van Achterberg, T. (2013). Prevalence of interpersonal trauma exposure and trauma-related disorders in severe mental illness. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4(1), 19985.

Mohan, R., McCrone, P., Szmukler, G., Micali, N., Afuwape, S., & Thornicroft, G. (2006). Ethnic differences in mental health service use among patients with psychotic disorders. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 41(10), 771-776.

Morgan, C., Mallett, R., Hutchinson, G., & Leff, J. (2004). Negative pathways to psychiatric care and ethnicity: the bridge between social science and psychiatry. Social science & medicine, 58(4), 739-752.

Muskett, C. (2014). Trauma‐informed care in inpatient mental health settings: A review of the literature. International journal of mental health nursing, 23(1), 51-59.

Phipps, M., Molloy, L., & Visentin, D. (2019). Prevalence of trauma in an Australian inner city mental health service consumer population. Community mental health journal, 55(3), 487-492.

Roberts, A. L., Austin, S. B., Corliss, H. L., Vandermorris, A. K., & Koenen, K. C. (2010). Pervasive trauma exposure among US sexual orientation minority adults and risk of posttraumatic stress disorder. American journal of public health, 100(12), 2433-2441.

Sweeney, A., Clement, S., Filson, B., & Kennedy, A. (2016). Trauma-informed mental healthcare in the UK: what is it and how can we further its development? Mental Health Review Journal.

Yatchmenoff, D. K., Sundborg, S. A., & Davis, M. A. (2017). Implementing trauma-informed care: Recommendations on the process. Advances in Social Work, 18(1), 167-185.

Podcast

Listen to Dr Jay Watts talking about “personality disorders” and trauma-informed care:

Photo credits

- Photo by Max Felner on Unsplash

- Photo by Ross Findon on Unsplash

- Photo by Susan Wilkinson on Unsplash

- Photo by IA SB on Unsplash

- Photo by Hannah Busing on Unsplash

- Photo by Rusty Watson on Unsplash