Internet-mediated interventions for mental health conditions are anticipated to become a key part of the future of healthcare with the hope that services can promise individualised mental healthcare, be low cost and widely available compared to current treatment options. As both utopian and dystopian visions inform how technology will shape the future, the reality of how technology can be used to improve mental health treatments needs thorough examination. As with all innovation, e-mental health treatments critically rely on the ideas, beliefs and methods of delivery that inform them: PTSD (post traumatic stress disorder) is certainly no exception.

As the most recent Office for National Statistics figures show, only around half of those that were assessed as meeting diagnostic criteria for PTSD were receiving treatment for the condition in the UK (ONS, 2014). The prevalence of PTSD is anticipated to rise as the refugee crisis further escalates. Developing innovative and widely-available PTSD treatments that make use of technological innovation is a promising avenue for treatment development.

iCBT, internet delivered Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, has been previously reviewed for PTSD interventions (Sijbrandij et al., 2016) that suggested internet-mediated PTSD interventions may be useful when supported by a therapist. This current review took a broader approach by reviewing RCTs for trauma-focused (TF) CBT, non-trauma-focused CBT and a range of other e-treatments.

Internet-based mental health care is anticipated to soon become a widespread form of care that may improve access and offer personalised treatment options.

Methods

Databases searched include Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsychINFO. This is a good range of databases, but the Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) (a database specific to PTSD and trauma literature) would have been a welcome addition to the search strategy.

Eligibility criteria was based on:

- RCTs comparing a psychological therapy administered by a web or mobile-based platform designed to treat symptoms of PTSD to a waitlist, TAU or active intervention

- Assessed and reported PTSD symptom severity immediately after intervention using a validated measure

- Included participants 18 years and over who had experienced a possible single-event trauma and did not require a formal diagnosis of PTSD

- Interventions that included additional guidance and feedback from a therapist or technical assistant were included and reviewed separately.

The reviewers assessed the risk of bias of articles using the Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies.

RCTs were sub-divided according to:

- Whether they compared an active treatment to another active treatment (active vs active) or to a waitlist or treatment as usual (active vs waitlist or TAU)

- Whether they used TF-CBT, non-TF CBT or another intervention that was not strictly designed using CBT approaches

The review further characterised studies according to the level of support provided during the intervention, which was grouped as follows:

- Therapeutic feedback

- Non-therapeutic technical support

- Online discussion

- Automated feedback only

- Group feedback from both a facilitator and peers

- No guidance

Post-intervention measures of symptom severity were the primary outcome. The I² statistic was used to test heterogeneity. Data were pooled and a random-effects meta-analysis conducted.

From an initial search of 2,984 papers in March 2015, 39 studies were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review, 33 of which were included in the meta-analysis with a total of 3,832 participants.

Seven papers included participants who met full PTSD diagnostic criteria. Other papers reported on a range of samples including students, military personnel, patients, health service professionals and parents of patients that report a wide range of trauma exposures (i.e traumatic medical procedures, bereavement, natural disasters, sexual trauma).

None of the studies reviewed were UK-based: countries where studies were carried out included the US (n=19), the Netherlands (n=5) Australia (n=4), Germany (n=3), Sweden (n=3), Switzerland (n=2), Canada (n=1) and Poland (n=1).

Results

Overall, the results suggest that e-mental health interventions may reduce PTSD symptom severity more effectively than active and TAU/waitlist controls. The details of the active and TAU treatments are summarised by the reviewers and active controls include working memory tasks, web-based psychoeducation and TAU at a primary care clinic. 18 studies used a waitlist control.

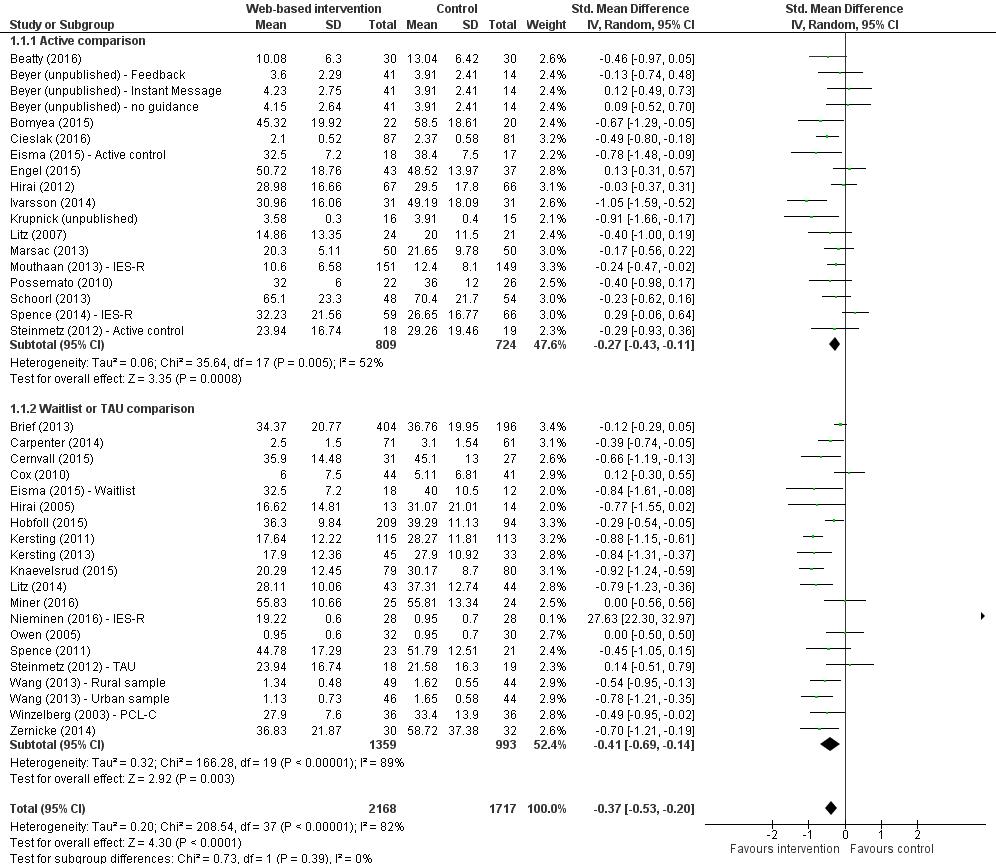

Primary analysis of all interventions (38 studies, 3,832 participants in total) found an SMD of -0.35 (95% CI -0.45 to -0.25, p<0.001) and high heterogeneity (I2=81%).

Within sub-groups:

E-Mental health interventions compared to active treatments (18 studies with a total of 1,533 participants) found an SMD of -0.27 (-0.43 to -0.11, p<.005) that favoured the e-mental health treatment with a moderate heterogeneity (I2=52%).

E-Mental health interventions compared to TAU and waitlist treatments (20 studies with a total of 2,352 participants) also favoured the e-mental health treatment with SMD of -0.41 (-0.69 to -0.14, p<0.001) with high heterogeneity (I2=89%).

TF-CBT found an SMD of -0.36 (-0.50 to -0.22 p<.001) and Non-TF CBT had an SMD of -0.24 (-0.48 to -0.21 p<.001), which both reduced symptom severity, with high (I2=92%) and moderate (I2=62%) heterogeneity respectively.

The pooled estimates suggest that e-mental health interventions may reduce PTSD symptoms severity, however the substantial heterogeneity of the results limits interpretation of pooled estimates.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that:

There is some evidence to suggest that these e-Mental Health treatments are effective at reducing PTSD-related distress over and above a variety of control conditions.

Strengths and limitations

- The search strategy and separate screenings of all articles by two reviewers was systematic and reproducible

- The substantial heterogeneity for the majority of sub-group analyses could have been addressed with further analysis. A meta-regression of other factors, such as sample size, population or symptom severity at baseline, could have been used to explain some of the heterogeneity (Guyatt et al. 2011)

- The authors also do not report on the severity of PTSD symptom-severity or examine differences between outcome measures used. Seven studies fulfilled the criteria for PTSD and the severity of symptoms in other populations is not outlined: suggesting that many participants are not within the ‘clinical’ range

- However, despite the range of approaches, sub-group and sensitivity analysis, which excluded studies with a high risk of bias and studies without PTSD as a primary outcome, the treatments consistently show a reduction in PTSD-related stress.

The heterogeneity of the studies in the meta-analysis limits the conclusions that can inferred.

Implications for practice

An internet-delivered treatment for a disorder that affects a large proportion of the population could benefit many by reducing waiting times and the burden on the limited availability for specialist trauma treatment. However, good-quality evidence is needed in order to develop effective interventions. All studies in the meta-analysis were rated as either weak (n=23) or moderate (n=15) for selection bias and 10 studies were rated as weak for overall design methods, which suggests the evidence reviewed is not of the highest quality. Robust evidence (that extends beyond a low p-value for a mean symptom outcome) is needed for research findings to have an impact on practice.

Overall, the study found some evidence to suggest that internet-delivered therapy may reduce PTSD-symptom severity. However, the range of treatments, outcome measures, baseline severity, study populations and overall heterogeneity of results as shown by I2 statistic limit the conclusions that can be drawn from the meta-analysis. Further sub-group analysis to explore the differences in studies would have been able to provide more insight into the most effective treatments and their commonly shared characteristics.

As the authors acknowledge, technology is rapidly developing and studies of efficacy must match the pace of these developments. The meta-analysis illustrates the need for further replication and analysis that can ascertain the most effective methods of delivery. Based on the smaller proportion of studies that involved clinical populations, online interventions may be more appropriate for members of the general population with mild PTSD symptoms rather than more complex and multiple-event traumas presented in clinical practice.

Technological development and better quality evidence is needed for e-interventions to be used in practice.

Links

Primary paper

Simblett S, Birch J, Matcham F, Yaguez L, Morris R. (2017) A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of e-Mental Health Interventions to Treat Symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress. JMIR Ment Health 2017;4(2):e14 DOI: 10.2196/mental.5558

Other references

National Statistics (2016) Mental Health and Wellbeing in England Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014 (PDF).

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R. et al (2011) GRADE Guidelines: 7. Rating the Quality of Evidence—inconsistency. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 64(12): 1294–1302.

Sijbrandij M, Kunovski I, Cuijpers P. (2016) Effectiveness of Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2016 Sep;33(9):783-91. doi: 10.1002/da.22533. Epub 2016 Jun 20. [PubMed abstract]