What guidance is there for managing mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic? A group of trauma experts co-ordinated by University College London is gathering resources for co-ordinating psychosocial support through the crisis. The site draws together evidence from external sources and new guidance produced by the working group, and is being expanded regularly as a rapid response to the pandemic.

This blog is based on the guidance that was produced by the COVID Trauma Response Working Group up to 10th April 2020. Currently there is specific guidance for: hospital staff involved in COVID-19 emergency care, patients suffering from COVID-19, those in quarantine, and community volunteers.

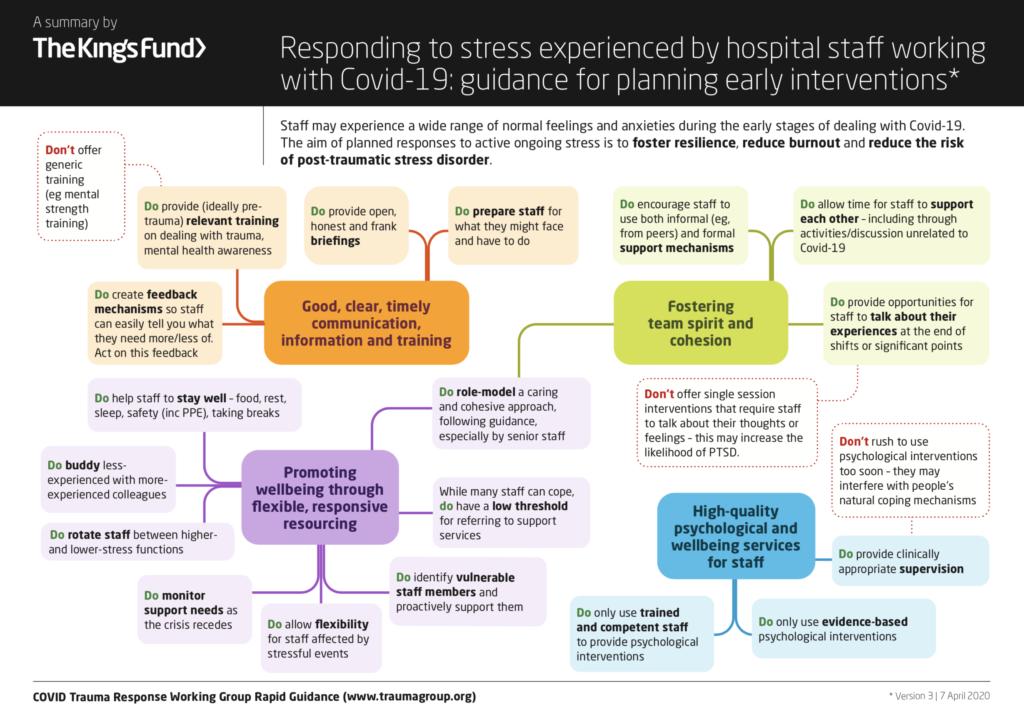

The group have also produced a video (see below) and their guidance has been helpfully summarised into a 1-page PDF diagram by The King’s Fund.

A trauma-focussed response to COVID-19 is important because evidence points to increased rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following pandemics (Wu et al., 2014). Being prepared for potential psychological effects of trauma resulting from the current outbreak could help protect people and organise services (Brooks et al., 2018). It is crucial to consider people’s experiences of COVID-19-related trauma in the context of their psychosocial circumstances, including existing mental disorder and socioeconomic position (The Lancet, 2020).

The pandemic’s effects on people working on the front line, including healthcare practitioners and essential workers supporting people living with consequences of coronavirus, is especially concerning. In particular, for hospital workers treating patients with COVID-19, the psychological impact of prolonged exposure to stressful conditions, fear of exposure to the virus and separation from loved ones could be profound. While the scale of this pandemic is unprecedented in recent history, encouragingly, studies of other types of disasters have found that humans are generally highly resilient to trauma (North, 2014).

Frontline workers face prolonged exposure to a combination of traumatic conditions on a scale that has never been seen before – how can guidance help?

Methods

The strengths and limitations of the rapid guidance have been assessed using the AGREE II instrument as a guide. The guidance is in its early stages. Produced rapidly out of necessity, it is therefore not reasonable to compare against standards used for guidance produced within a more typical timeline. With this in mind, the following assessment is based on the content available to date (10th April 2020).

As the guidance authors point out: “We need to adapt our guidance and interventions as the situation evolves”. The overall set of external resources listed was considered and gaps were identified in available recommendations. However, each external set of guidelines was not individually reviewed.

In disaster settings, guidance must be produced rapidly and regularly adapted to unfolding events.

Key points

The guidance focuses on the needs of healthcare staff. There are unique challenges for healthcare staff working in the current crisis. Providing open and honest communication, supporting teams to look out for vulnerable colleagues, and offering training on potential effects of trauma and trauma management skills, could help staff to manage the trauma they are faced with and reduce the risk of them developing a mental health disorder. Other recommendations include:

- A phase-based response; in the early stages of the crisis, ensuring physical safety and adequate food, rest and psychological support. Formal psychosocial support may be needed by some as the crisis develops.

- Evaluation of the effects of the crisis and effectiveness of interventions in different groups.

The authors also provide links to externally-produced information including guidance for the general population, volunteers, and children and adolescents.

Open and honest communication, supporting teams to look out for vulnerable colleagues, training and trauma management skills could help staff to manage trauma and prevent mental illness.

Strengths and limitations

The scope of the guidance is broad and aims to support those coordinating psychosocial responses to COVID-19. A collection of existing guidance from a variety of external sources is available alongside the newly produced set, enabling a rapid response, which is vital in this fast-moving crisis. The group is also drawing on evidence from countries, such as China, that experienced the virus outbreak earlier.

The recommendations are based on existing guidance, research evidence and expert opinion of the working group. Another key consideration by the experts was the translation of guidance in different languages (6 so far).

As with the rapid COVID-19 guidance produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), some formal processes, such as public consultation on the guidance and the use of formal evidence assessment tools, have been sacrificed so that the guidance can be made available quickly.

Some potential gaps have been identified from reviewing the current rapid guidance. Further updates should consider:

- Involvement of people with lived experience.

- High risk groups including those with existing mental disorder, those who have self-harmed, people experiencing homelessness and others who may particularly struggle to carry out social distancing or isolation.

- How social support for individuals and communities can be enabled during social distancing and isolation.

Further updates of this guidance should consider the involvement of people with lived experience and targeting high risk groups.

Implications

Accessing formal and informal social support is key to protecting individuals from increased risks of trauma and suicidality following disasters (Guo et al., 2018) and to allow communities to adapt positively (Abramson et al., 2015). The current pandemic and social distancing rules pose particular challenges. Adaptations to existing mental health services are needed to ensure people can still access care. The possible increase in demand for mental health care following the pandemic will require long term funding commitments. In addition, we know from previous research that the way governments respond to economic crises can affect rates of suicidal behaviour (Norstrom and Gronqvist, 2015). Financial protection could help mitigate some of the trauma of sudden unemployment and job insecurity following the COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent economic recovery.

Some people with existing mental health conditions may be more at risk of their symptoms worsening as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic (Yao et al., 2020). People with existing mental illness are at greater risk of developing PTSD following major disasters (North, 2014). The negative effects of self-isolation can also be greater for people with existing mental health difficulties (Brooks et al., 2020). In addition, mental health service users have voiced fears about attending A&E following self-harm due to resources being even more stretched than usual. Given that suicide rates can increase following disasters (Guo et al., 2018), it is crucial that emergency healthcare is still available for people who already have raised risks of suicide.

But eventually, there may be a silver lining. Collective trauma provides a rare opportunity for conversations about mental health to take place on a large scale. A group of people with lived experience of mental health problems have launched an initiative to collate sources of information and support starting during the COVID-19 pandemic (Check out @MadCovid on Twitter). Some people with experience of living with mental health difficulties have spoken of a specific capacity to manage in the current crisis in ‘Mad Covid Diaries’.

There is little in terms of research evidence for this, but those with lived experience have provided accounts of symptoms easing and feeling well-placed to provide emotional support to others. The reasons behind this are complex and are also likely to be unique to personal circumstances. However, the potential for traumatic experiences to give way to personal growth has been demonstrated in previous disasters (Jin et al., 2014). There is also potential for teams and communities to adapt positively and find creative approaches to supporting people who are vulnerable to traumatic effects of the crisis.

Accessing formal and informal social support is key to protecting people from increased risks of trauma and suicidality following disasters and to allow communities to adapt positively.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary Link

COVID trauma response working group rapid guidance for planners of the psychosocial response to stress experienced by hospital staff associated with COVID: Early Interventions (2020). COVID Trauma Response Working Group.

The King’s Fund have developed a brilliant summary of the guidance, which you can download here.

Other references

ABRAMSON, D. M., GRATTAN, L. M., MAYER, B., COLTEN, C. E., AROSEMENA, F. A., BEDIMO-RUNG, A. & LICHTVELD, M. 2015. The Resilience Activation Framework: a Conceptual Model of How Access to Social Resources Promotes Adaptation and Rapid Recovery in Post-disaster Settings. Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 42, 42-57.

BROOKS, S. K., DUNN, R., AMLOT, R., RUBIN, G. J. & GREENBERG, N. 2018. A Systematic, Thematic Review of Social and Occupational Factors Associated With Psychological Outcomes in Healthcare Employees During an Infectious Disease Outbreak. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 60, 248-257.

BROOKS, S. K., WEBSTER, R. K., SMITH, L. E., WOODLAND, L., WESSELY, S., GREENBERG, N. & RUBIN, G. J. 2020. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet, 395, 912-920.

GUO, J., LIU, C., KONG, D., SOLOMON, P. & FU, M. 2018. The relationship between PTSD and suicidality among Wenchuan earthquake survivors: The role of PTG and social support. Journal of Affective Disorders, 235, 90-95.

JIN, Y., XU, J. & LIU, D. 2014. The relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic growth: gender differences in PTG and PTSD subgroups. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 1903-1910.

NORSTROM, T. & GRONQVIST, H. 2015. The Great Recession, unemployment and suicide. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69, 110-116.

NORTH, C. S. 2014. Current Research and Recent Breakthroughs on the Mental Health Effects of Disasters. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16.

THE LANCET, P. 2020. Send in the therapists? The lancet. Psychiatry, 7, 291-291.

WU, Z., XU, J. & HE, L. 2014. Psychological consequences and associated risk factors among adult survivors of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Bmc Psychiatry, 14.

YAO, H., CHEN, J.-H. & XU, Y.-F. 2020. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. The lancet. Psychiatry, 7, e21-e21.

Photo credits

- Photo by Luis Melendez on Unsplash

- Photo by Darius Bashar on Unsplash

- Photo by Obi Onyeador on Unsplash

- Photo by Branimir Balogović on Unsplash

- Photo by Aljoscha Laschgari on Unsplash

- Photo by Dhaya Eddine Bentaleb on Unsplash