[Note: today’s blog is very much a group effort. It’s been written by more than 20 MSc students at University College London who had an elf (yours truly) gatecrash their journal club on Wednesday! Do let me know if you want me to infiltrate your journal club. We elves have our ways you know.]

Previous research has found associations between trauma and psychotic symptoms. However, the search for causality continues. According to the Bradford Hill criteria, several requirements must be fulfilled in order to establish causality.

We already know from past evidence that associations between trauma and psychosis have been robustly replicated with evidence of a clear dose-response relationship (Varese et al, 2012; van Dam, 2012). Evidence also suggests that a temporal sequence exists between trauma and psychosis and that resolving trauma reduces psychotic symptoms.

However, studies have not fulfilled a remaining criterion; that plausible theory-based mechanisms explain the associations between trauma and psychosis. This new study (Hardy et al, 2016) aims to address this gap in our knowledge.

This study had two aims.

- The first was to replicate the previously established association between trauma and psychotic symptoms

- The second was to test their theory-based hypotheses about potential causal mechanisms.

To test the first aim, the authors hypothesised that childhood sexual abuse would be associated with auditory hallucinations, and that childhood physical abuse would be associated with paranoia.

To test the second aim, they proposed four hypotheses:

- Intrusive trauma memories were hypothesised to mediate the association between childhood sexual abuse and hallucinations

- They hypothesised that negative beliefs about the self and others mediated the association between childhood physical abuse and paranoia

- Trauma-related affect regulation (numbing, avoidance and hyperarousal) was hypothesised to mediate the relationship between all trauma types and all psychotic symptoms

- They also proposed that depression mediates the relationship between all trauma types and all psychotic symptoms.

This study aimed to identify underlying trauma-related mechanisms and thereby strengthen the argument that trauma causes psychosis.

Methods

228 participants were recruited from 4 NHS trusts in London and East Anglia, via a UK randomised controlled trial of CBT and family intervention for psychosis.

Inclusion criteria

- Aged 18-65

- Recent relapse in positive symptoms

- Diagnosis of non-affective psychosis

- Score of 4 of the Positive and Negative Syndrome scale (PANSS).

Exclusion criteria

- Primary diagnosis of a substance misuse, learning disability, or organic syndrome

- Insufficient level of English.

Measures

Cross-sectional design, included five measures:

The Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ)

- An assessment of:

- Non-victimisation: Illness, natural disasters, accidents

- Victimisation: Sexual abuse, Physical abuse and Emotional abuse

- If participants reported at least 1 event, they were asked to indicate which trauma they were currently most affected by as their ‘index event’

- All reported events were categorised into childhood, adulthood, or lifetime

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (SRS- PTSD): This looked at PTSD symptoms in relation to the event that the participants reported they were most affected by.

The Scales for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms: Looking at positive symptoms of psychosis over the past month

The Brief Core Schema Scale (BCSS): To assess the core beliefs; either on the self-belief or negative-other scales

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II): Depression is assessed over the past fortnight.

Analysis

The analyses were carried out in 3 stages:

- Associations between all trauma types and symptoms of psychosis

- Those associations that were found to be significant were then assessed to look at the total effect of trauma exposure on symptoms of psychosis

- Effect of trauma exposure on the mediators, using a linear regression

- Both of these stages adjusted for age, gender, and ethnicity as potential confounders

- Only those trauma-outcome and trauma-mediator relationships which were statistically significant at the 10% level were carried forward into the mediation analysis

- Mediation analysis was then done to test whether a proposed mechanism can explain the association between trauma and psychosis

- A framework was used at this stage, and it allowed for the estimate of the Natural Direct Effects (NDE) and Natural Indirect Effects (NIE).

If the NIE pathway was statistically significant, this would reflect a partial indirect effect of the mediator. However, if the NDE pathway was also found to be non-significant, then this would be considered evidence of full mediation.

Results

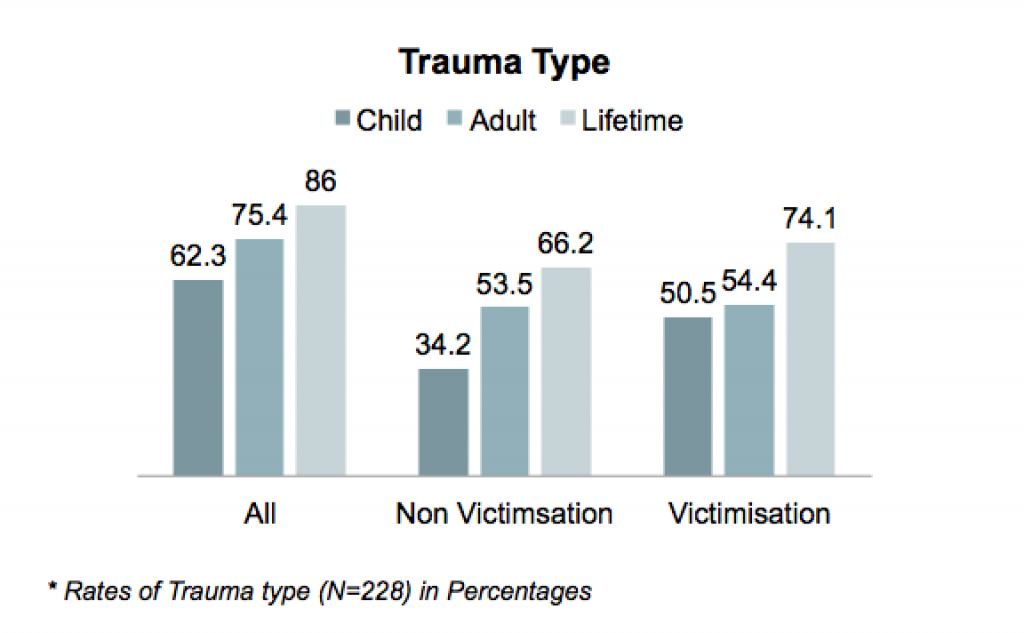

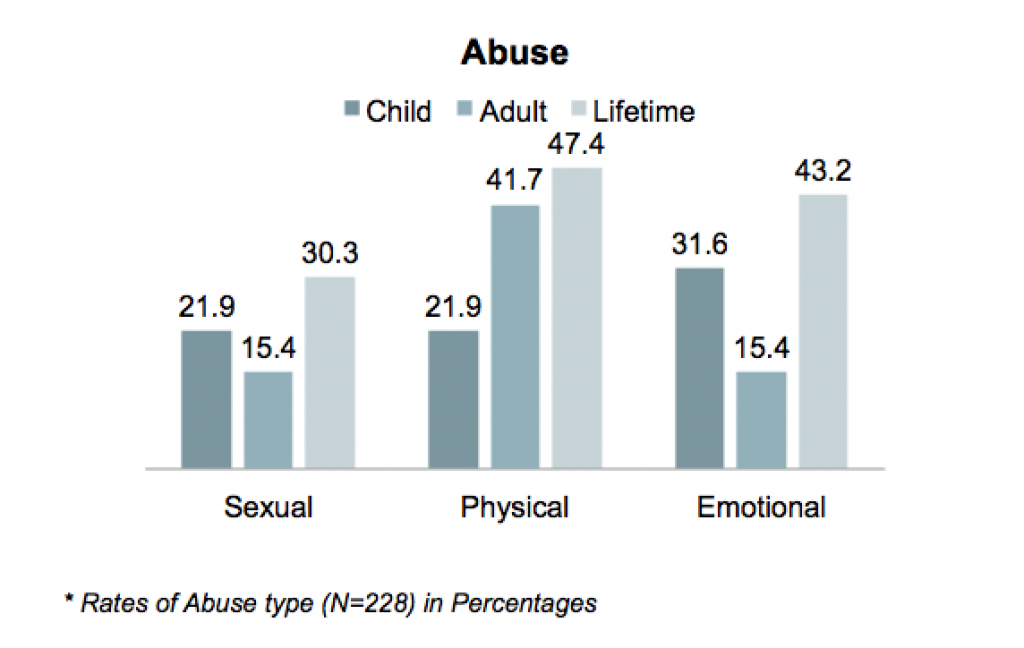

- The authors of the study divided the rates of trauma and abuse, on the different prevalent rates, based upon the participant response on the Trauma History Questionnaire (THQ):

Majority of the participants had experienced some form of trauma during their lifetime (N=86%), with most of them reporting at least a single event of victimisation (N=74%), and two-thirds reporting trauma due to non-victimisation (N= 66%).

One- third of the participants experienced sexual abuse in their lifetime (N=30%), almost half of them experienced both physical abuse (N=47.4%) and emotional abuse (N=43%), respectively.

- The researchers found a statistically significant association between child sexual abuse with auditory hallucinations (OR = 3, CI = 1.2 to 4.3, P = 0.12)

- They did not find a statistically significant association between child physical abuse and paranoia (OR = 1.2, CI = 0.6 to 2.3, P = 0.555)

- Interestingly, going beyond the scope of the hypothesis in the study, the authors found a statistically significant association between child emotional abuse and persecutory beliefs (OR = 1.9, CI = 1.1 to 3.5, P = 0.022) and delusions of reference (OR = 2.1, CI = 1.2 to 3.8, P=0.009)

- The study found an indirect effect of cognitive-affective factors of post-traumatic avoidance, numbing (OR = 1.475, SE = 188, P = 0.038) and hyper-arousal (OR = 1.439, SE = 0.184, P = 0.048) on the development of auditory hallucinations when someone is exposed to child sexual abuse

- Further, the study found similar indirect effect of negative other beliefs on the development of delusions of persecution when an individual was exposed to child emotional abuse (OR = 1.359, SE = 0.136, P = 0.024).

As expected, this study found that childhood sexual abuse was associated with hearing voices, and childhood emotional abuse with paranoia.

Conclusions

The authors concluded:

This study is the first to demonstrate that trauma-related psychological mechanisms mediate victimization and psychotic symptoms associations in a large sample of people with relapsing psychosis.

The identification of theoretically based psychological processes underlying specific associations between events and symptoms provides further support for the causal role of trauma in psychosis.

This the first evidence for theory in the relationship between trauma and subsequent psychosis is particularly interesting because they found that the mediators depended on the different types of trauma (emotional, sexual, physical). The authors concluded that these trauma-specific mechanisms could suggest a new direction for practice in the near future; providing tailored treatments for different types of victimisation.

It certainly does seem to resonate with growing prophecies of an age of personalised medicine, but we aren’t quite there yet. Translating research into practice is a long process, and requires lots of high quality research. Which begs the question: how did this study fare in the critical review of keen eyed MSc students?

Strengths and limitations

One particularly important aspect of this study is that it was the first of it’s kind (while previous studies had investigated the link between trauma and psychosis, no past research had looked at what variables mediated this relationship); nobody had looked at why the relationship occurred. The study was also novel in terms of exploring links between specific types of trauma and specific psychotic symptoms. Acknowledging the variation of different trauma types and different symptoms is of great importance for both research and clinical practice.

Although the importance of investigating mediators of the trauma/psychosis relationship is undeniable, there are difficulties with accepting the conclusions about these mediators, given the methodology used in the study. A cross sectional design was used, meaning that data collection for all variables happened at the same time. Accounts of trauma were therefore retrospective. This creates several issues:

- Individuals might be more likely to have selectively reported more recent trauma

- Subsequent experience of treatment might affect retrospective reports of trauma if individuals are exploring past events in therapy

- But mainly, we don’t know that a variable is a mediator unless we know that it occurred before the outcome and in this study, we can’t make this assumption.

One way to test this would be to measure trauma and mediators first and then measure outcome at some later stage, in other words, to use a prospective cohort or longitudinal study design. But this kind of design comes with its own demands, requiring a larger sample, considerable ethical consideration, more time and money. Finding some compromise between this and the design the author’s used might be the best option for investigating this area further.

Another issue that may need to be improved upon in further research is how trauma events are categorised. In this study, a given trauma event was categorised by researchers as either childhood emotional, physical or sexual abuse. There was no consideration for trauma events that may have fallen into more than one category, but if sexual abuse is experienced, surely this could be experienced as emotional abuse as well? This categorisation undermines the results because it means that accurate measurement of trauma types is not guaranteed. Also, inclusion of other specific trauma types would have been useful. Neglect, for example, which has been linked with psychosis in males in particular, is not included as a trauma category.

The retrospective nature of this study makes it susceptible to various forms of bias.

Implications

Seeing as this was a study in a novel area, the evidence regarding the mechanisms leading to psychosis is still very tentative; however, Hardy et al.’s (2016) research does prompt interesting questions. Considering the evidence discussed, our questions regarding implications of this research are three fold.

- Firstly, does this suggest interventions such as CBT should be used to target specific psychological mechanism? For example, if research shows that negative self-belief mediates the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and auditory hallucinations, should we target this?

- Secondly, should professionals who work directly with service users be looking into a service users history for signs of trauma? As a service user, is this something that you would find helpful, or would it be more like opening a can of worms?

- Finally, there has been a lot of caution around using psychodynamic approaches in the treatment of psychosis. But might asking the service user to look back into their own history highlight potential mechanisms?

Huge thanks to the amazing UCL Psychiatry Mental Health Sciences Masters students, who did a sterling job to complete this blog after an especially gruelling journal club!

Links

Primary paper

Hardy A, Emsley R, Freeman D, Bebbington P, Garety PA, Kuipers EE, Dunn G, Fowler D. (2016) Psychological Mechanisms Mediating Effects Between Trauma and Psychotic Symptoms: The Role of Affect Regulation, Intrusive Trauma Memory, Beliefs, and Depression. Schizophr Bull (2016) 42 (suppl 1): S34-S43 doi:10.1093/schbul/sbv175

Other references

Varese F, Smeets F, Drukker M, Lieverse R, Lataster T, Viechtbauer W, Read J, van Os J, Bentall RP. (2012) Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38:661–671.

van Dam DS, van der Ven E, Velthorst E, Selten JP, Morgan C, de Haan L. (2012) Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42:2463–2474. [PubMed abstract]

Trauma and psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we really understand why? https://t.co/aYLuLEsqGs

Today @MentalhealthMSc students on psychological mechanisms that mediate effects btwn trauma & psychotic symptoms https://t.co/acPWfFAlmD

Trauma and psychotic symptoms: clear association but do we really understand why? https://t.co/hCwHxdJdYy @MentalhealthMSc for @Mental_Elf

Hi @SlowMoTherapy @richardaemsley @ProfDFreeman We’ve blogged about your trauma & psychosis paper https://t.co/acPWfFAlmD < Any response?

@Mental_Elf @SlowMoTherapy @richardaemsley @ProfDFreeman so I was right then!

Many thanks @Mental_Elf @MentalhealthMSc – great blog! We agree cross-sec design sig limitn. Will reply to other imp points u raise on w/e

New research finds childhood sexual abuse was assoc with hearing voices & childhood emotional abuse with paranoia https://t.co/acPWfFAlmD

@Mental_Elf Adverse childhood experiences are associated with nearly every negative outcome we can measure!

#Trauma & psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we really understand why? https://t.co/uXyYRhI05p @Mental_Elf on the #evidence

Shld CBT target negative self-belief if it mediates relationship btwn childhood sex abuse & auditory hallucinations https://t.co/acPWfFAlmD

#Trauma, cognitive- affective factors and #psychosis: association or causation?https://t.co/UE0N3SBA3o

RT @Mental_Elf: Trauma and psychotic symptoms

Clear association, but do we really understand why?

https://t.co/acPWfFAlmD https://t.co/6fRe…

Hi I am struck by the relatively low odds ratios of 1.5 for proposed mechanisms – that’s a very mild relationship suggesting not very causal. Would also be nice to know how much variance was explained by these psychological mechanisms

Weak strength of relationship between proposed psychological mechanisms for trauma▶️psychosis @Mental_Elf https://t.co/xFYjTFWUQO

@SameiHuda @Mental_Elf Now that’s an amazing outcome of a journal club!

@pishnotposh @Mental_Elf I thought they did well I struggled to grasp that paper

https://t.co/QZmpIYpK6f

RT @Mental_Elf: New evidence demonstrates that trauma-related psychological mechanisms mediate victimisation & psychotic symptoms https://t…

#Trauma and psychotic symptoms — clear association, but do we really understand why? #MHealth #psychosis https://t.co/hEg3vRfWrJ

Most popular blog this week?

Trauma and psychotic symptoms

By the #UCLJournalClub @MentalhealthMSc students… https://t.co/v9Sq846P89

@Mental_Elf @MentalhealthMSc horrific if you think about the level of coercion in MH care and likely retraumatisation

Trauma and psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we really understand why? https://t.co/Dd0BLWT2hR via @sharethis

Trauma and psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we really understand why? https://t.co/Byxg9sF2H3

#Trauma and #psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we know why? https://t.co/Isbq0Zo8HM https://t.co/ygu7yCZi76

#Trauma and #psychotic symptoms: clear association, but do we really understand why? https://t.co/SA40M0pGRp via @sharethis

Hi Mental Elf and the UCL Journal Club,

Sorry for the slow reply and thanks for your blog! We appreciate your feedback about the paper. It’s very helpful to highlight the complexities of conducting research in this important area. We totally agree that we don’t fully understand the relationship between trauma and psychosis. The pathways are multifaceted and will vary from person to person, there’s so much we don’t yet know. At the same time, it’s encouraging that theoretical models are being developed and tested, with the aim of improving trauma-focused care. Our study aimed to build on this work by investigating theoretically-informed mediators in a group of people with persisting psychosis.

We agree the cross-sectional design is a limitation of the study. But, like you say, conducting a longitudinal case-control study in this area is challenging, raising significant practical, ethical and safeguarding issues. Assessing childhood victimisation and its consequences prospectively is also difficult to do accurately, given the factors that might understandably impact on whether a child discloses what is happening. Given these obstacles, we took a pragmatic approach and used a retrospective, case-control design to try to further understanding of the relationship between trauma and psychosis.

So, as you rightly considered, what can our design tell us about the underlying mechanisms? The assessment of childhood victimisation is retrospective, so there is a case for assuming it occurred prior to the trauma-related mediators and psychosis outcomes. However, we agree of course that memory is inherently subject to recall bias (Colman et al, 2016, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291715002032). The assessment of post-traumatic stress is anchored to the reported index event, which increases the likelihood that avoidance, numbing and hyperarousal mediators were post-traumatic processes.

However, assessing trauma-related processes in psychosis is complex. There is a significant overlap in the phenomenology of post-traumatic stress and psychosis (Fornells-Ambrojo et al, 2016, DOI: 10.3402/ejpt.v7.32095) and, in the context of childhood victimisation, people may not have experienced or be able to recall a period prior to trauma, from which to anchor the onset of post-traumatic difficulties. And of course, post-traumatic stress and psychosis are likely to interact, which further complicates the picture (Mueser et al, 2002, DOI: 10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00173-6).

You mention finding a compromise between prospective and cross-sectional designs. We’d be interested to hear further thoughts about this. Investigating the relationships between trauma-related processes and psychosis outcomes over time seems a potential way forward. Unfortunately, in the PRP trial we were only able to measure post-traumatic stress processes at one time-point so this analysis was not possible.

As you indicate, it is also important to consider that victimisation types do not occur in isolation from each other, and other research has indicated a dose-response relationship between trauma and psychosis. We did examine the impact of cumulative trauma and combined trauma types (see the supplementary material for the paper). In contrast to previous findings, we did not find a significant effect of cumulative events or combined trauma types on psychosis outcomes, although childhood sexual abuse and emotional abuse were associated with more severe negative-other beliefs and post-traumatic hyperarousal. The lack of cumulative effect of trauma was unexpected, and perhaps provides further support for the specificity of trauma type on psychosis?

However, our assessment of trauma severity was limited. Measuring severity is also complex, and can be defined by a number of attributes (e.g. trauma type, frequency, duration, proximity, perpetrator characteristics, physical harm, etc.). We don’t yet know which are most relevant to understanding the impact on psychosis. Psychological models suggest the subjective appraisal and consequences of experiences may be more important than the objective characteristics of events, and this may be a more helpful focus for future research. We agree the lack of assessment of neglect was a significant omission, especially given findings implicating the role of attachment in psychosis (Berry et al, 2007, DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.006). Arguably negative beliefs and affect regulation are aspects of attachment, and we would view our findings as consistent with this work. We hope that future studies will incorporate a broader assessment of trauma, moving away from stringent event definitions that focus primarily on physical, not psychological, threat (e.g. DSM 5, APA, 2013).

We very much agree with the comments that the replication of the association between trauma and psychosis is not novel. There have been a number of studies demonstrating specificity of relationships, with some equivocal findings (Bentall et al, 2014, DOI: 10.1007/s00127-014-0914-0). The role of trauma-related processes on psychosis has also been investigated (see Gibson et al, 2016, DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.08.003, for a recent review) and we were inspired by this research. To the best of our knowledge, the strength of our study was to investigate mediation by theoretically informed mechanisms in a sample of people with persistent psychosis. We agree that the effect of the mediators was modest – perhaps because the pathways from trauma to psychosis are multifactorial, and there were putative processes that we did not comprehensively assess (e.g. dissociation).

As you highlight, the findings underscore the importance of assessing trauma and trauma-related consequences. This is national policy in mental health services however the implementation is poor (Brooker et al, 2016, DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.186122; NICE, 2014). Obstacles to implementation need to be addressed and a culture of enquiry embedded in all public services. I note your comment about whether this would be ‘opening a can of worms’, as this can also be a concern for clinicians and service users. The available evidence suggests that people want to be asked, and it is essential that clinicians provide people with the opportunity to disclose, if they wish. However, there has been relatively little research on how people who have experienced victimisation and psychosis would like to be asked about their experiences, and the possible impact of individual and cultural factors. Improving practice in this area is of course a necessary foundation for effective trauma-informed care.

And what about the translational implications for talking therapies? Well, the findings of our study already have tentative support from a recent trial, and are in line with developments in clinical practice and best practice recommendations (NICE, 2014). Cognitive-behavioural models of psychosis have long emphasised the role of developmental factors in understanding a person’s difficulties, and the current impact of these factors highlight potential targets for therapy. For example, modifying trauma-related beliefs and coping in trauma-focused CBT for psychosis has been previously recommended (Smith et al, 2006, ISBN-10: 1583918205). A recent trial of Prolonged Exposure and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing therapy for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in psychosis found these trauma-focused therapies led to reductions in both trauma-related beliefs and paranoia (de Bont et al, 2015, DOI: 10.1017/S0033291716001094; van den Berg et al, 2015, doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2637). In the South London & Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, we are working to improve the provision of trauma-focused therapy across our psychosis services, and are aware of similar initiatives nationwide and internationally. These efforts are promising, although there is much work to do – both in the prevention of childhood adversity and ensuring people who experience victimisation and psychosis have access to the support they need.

Thanks again for reviewing our paper,

Amy

Nice study but its clearly not the case that this is the first to look at potential psychologicaal mechanisms mediating between childhood adverse experience and psychosis. Several previous studies, including one of my own, have found evidence supporting the childhood sexual abuse – dissociation – hallucinations pathway (Varese, F., Barkus, E., & Bentall, R. P. (2011). Dissociation mediates the relationship between childhood trauma and hallucination-proneness. Psychological Medicine, 42, 1025-1036; Perona-Garcelán, S. P., Carrascoso- López, F., García-Montes, J. M., Ductor-Recuerda, M. J., López, J. A. M., Vallina-Fernández, O., . . . Gómez-Gómez, M. T. (2012). Dissociative experiences as mediators between childhood trauma and auditory hallucinations. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 323-329. doi:10.1002/jts.21693) and we have also looked at insecure attachment as a mediator between parental neglect and paranoia (Sitko, K., Bentall, R. P., Shevlin, M., O’Sullivan, N., & Sellwood, W. (2014). Associations between specific psychotic symptoms and specific childhood adversities are mediated by attachment styles: An analysis of the National Comorbidity Survey. Psychiatry Research, 217, 202-209. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.01).

[…] Social models of madness and distress have been explored in an earlier blog by Alison Faulkner, and this paper adds another dimension to the blog discussion on research into the connections between trauma and psychotic symptoms. […]

[…] of adverse childhood experiences on mental health have been blogged about for the Mental Elf, here and here and earlier work by Sweeney and colleagues on trauma-informed approaches appeared in a […]