For anyone familiar with the symptoms of psychosis, it’s not surprising that hallucinations and voice-hearing can be traumatic for the individual experiencing them. A first episode of psychosis can challenge an individual’s understanding of themselves and others in a similar way to traumatic events that do not involve symptoms of psychosis.

However, the way in which these symptoms themselves, their social stigma and their treatment may lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complicated issue. Psychotic symptoms fall outside of what the DSM defines as traumatic as they do not fulfil the criteria of being an “exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence”, which prevents a diagnosis of PTSD based on the experience of psychotic symptoms alone. Service users diagnosed with psychosis are likely to report prior experiences of trauma and have a co-morbid diagnosis of PTSD.

Further to this, there is the argument that psychosis itself may be a response to trauma: which accounts for the high co-morbidity between psychosis and PTSD and high levels of trauma in those diagnosed with psychosis (Morrison, Frame, & Larkin, 2003).

Genetic research also suggests that there may be overlapping genes that carry both a risk for PTSD and psychosis (Oconghaile & Delisi, 2015).

Rodrigues and Andersons’ recent systematic review attempts to gain a better understanding of the relationship between the first episode of psychosis (FEP) and symptoms of PTSD that are attributed to experiences of psychosis. Traumatic events were assessed irrespective of the DSM definition of trauma and looked to further provide insight into how trauma may arise after experiences of psychosis.

Psychotic episodes and exposure to events that are defined as traumatic according to DSM criteria can be similarly distressing.

Methods

Databases searched include Cochrane Library, MEDLINE-Ovid, EMBASE-Ovid, Web of Science, PsychINFO, and Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS) PILOTS.

Eligibility criteria was based on:

- If the population were FEP or stratified according to single or multiple episodes

- PTSD symptoms were measured in reference to psychosis or associated treatment

- Restricted inpatient and unrestricted outpatient/community samples were included

- Self-report measures and clinical interviews for psychosis and clinical diagnosis and screening for PTSD were included.

Studies were analysed in sub-groups based on the following criteria:

- Whether they used self-report scales to assess PTSD symptoms or diagnosis for PTSD by clinical assessment

- Reported affective and non-affective psychosis

- Regional differences in PTSD symptom prevalence

- Divided between restricted inpatient and unrestricted inpatients/outpatients.

A synthesis of qualitative studies that fulfilled study criteria was also used to summarise aspects of psychosis and its treatment that were reported as traumatic.

Results

From the initial 1,186 studies that were found, 13 studies met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis and nine qualitative studies were included in the review.

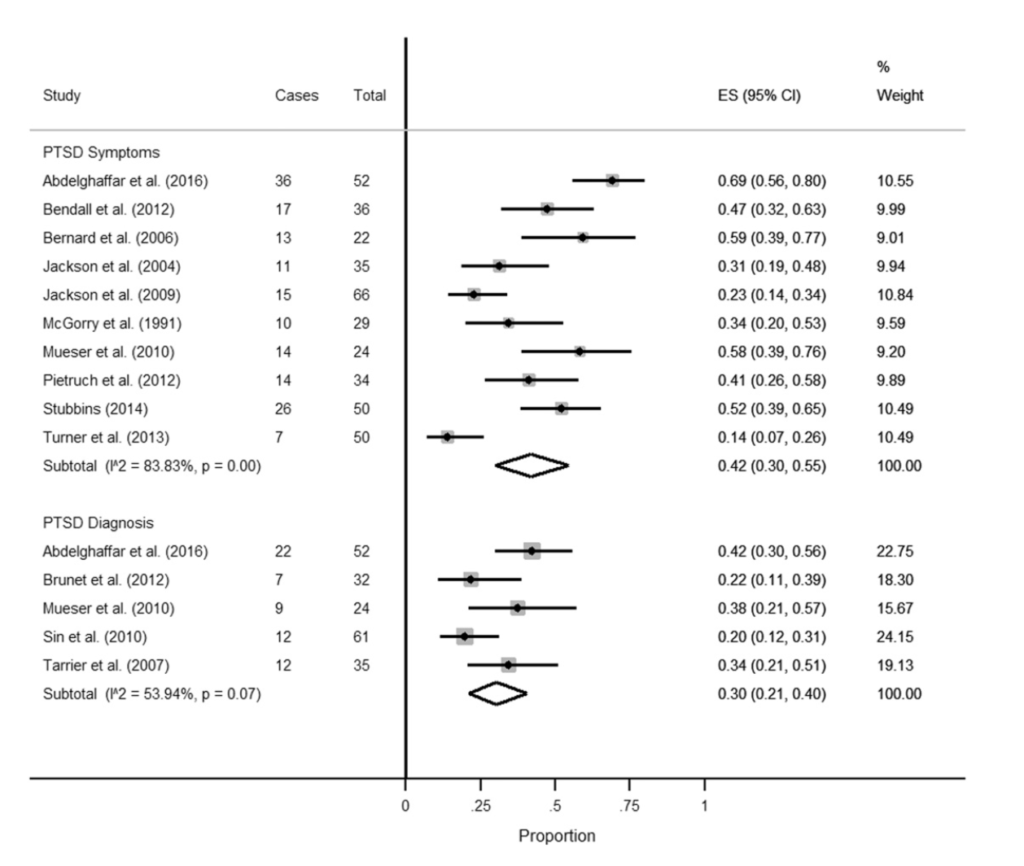

- Based on results from eight studies, 42% of people with FEP were found to have PTSD symptoms related to psychosis (95% CI = 30% to 55% I2=83.8%)

- Pooled results from four studies found 30% of people with FEP met diagnostic criteria for PTSD (95% CI = 21% to 40%, I2= 53.9%)

- Qualitative results identified a range of factors relating to both the symptoms of psychosis and the experience of hospitalisation or treatment as sources of trauma

- Higher prevalence rates were found in studies that used self-report measures compared to clinical assessment

- Funnel plot analysis did not find evidence of publication bias.

Forest plot of the prevalence and 95% confidence intervals of the prevalence of PTSD symptoms following the first episode of psychosis.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

The experience of FEP – including pathways to care, hospitalization and treatment – can be sufficiently traumatic… we need evidence-based interventions to treat PTSD symptoms in the context of FEP.

Strengths and limitations

- The search strategy was comprehensive and reproducible

- The quality criteria identified studies that did not adjust for main confounders or additional confounders

- Overview of qualitative evidence gives some insight into the different ways in which FEP can be traumatic

- Sub-group and sensitivity analysis was thorough: results were analysed to detect any differences based on regional differences, affective/non-affective psychosis, use of self-report or clinical assessment of trauma symptoms and quality assessments of studies

- The review was limited by high non-participation rates across studies, none of the studies fulfilled all the requirements of the review’s quality criteria assessment and the results were highly heterogeneous

- There was an absence of information regarding the assessment of prevalence of PTSD that was not related to psychosis or exposure to trauma prior to the first episode of psychosis. This may be due to the cross-sectional designs of the studies that may not have been able to ascertain information about the patient prior to FEP.

The majority of studies included were cross-sectional: longitudinal designs may be more appropriate to chart the development of PTSD in individuals diagnosed with psychosis over time.

Implications for practice

This review provides an interesting insight into a large percentage of FEP patients that report PTSD symptoms related to their experience of psychosis or its treatment. The approach of the review challenges the idea that the definition of trauma should be restricted to life-threatening situations and include distressing symptoms associated with mental health problems. Practitioners and service users may benefit from a greater awareness of how experiences of psychosis, which fall outside of the DSM criteria for trauma, may contribute to PTSD diagnoses and symptoms.

Whether the presence of PTSD is due to FEP or other pre-existing traumas that may be triggered by FEP is something that this analysis was unable to address. What the study does do is highlight the prevalence of PTSD in FEP patients, which suggests that trauma-focused treatments in cases of FEP psychosis may improve the well-being of many FEP patients and that an awareness of how treatment can be traumatic should be considered by practitioners.

Better quality evidence is needed to understand the relationship between prior trauma, first episodes of psychosis and subsequent symptoms of PTSD: this temporal relationship would best be established with longitudinal study designs and studies that examine both trauma that is related to FEP and trauma that is not in individuals that experience FEP. The review also highlights the paucity of knowledge around risk factors that may lead to PTSD following FEP. Nevertheless, the study does support that trauma related to FEP is something that should be further considered in practice and understood as sufficient for a diagnosis of PTSD.

Assessments of PTSD related both to prior trauma and experiences of psychosis may improve patient well-being and give us an insight into the relationship between the two conditions.

Links

Primary paper

Rodrigues R, Anderson KK. (2017) The traumatic experience of first-episode psychosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.045

Other references

Morrison AP, Frame L, Larkin W. (2003) Relationships between trauma and psychosis: a review and integration. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(4), 331–353. [PubMed abstract]

Oconghaile A, Delisi LE. (2015) Distinguishing schizophrenia from posttraumatic stress disorder with psychosis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(3), 249–255. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000158

Photo credits

- August Natterer [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

- Reku Papa CC BY 2.0

- Bjoern Breitsprecher CC BY 2.0

- Ky CC BY 2.0

I care for a person with schizophrenia. She has false memories due to delusions, and I believe she has potential PTSD because she believes these memories to be absolutely true. A person who has suffered physical trauma only has their memories* so why should someone whose memories are a delusion not also develop PTSD? It seems entirely plausible to me.

*and sometimes scars, but I’m speaking of the mental aspect.

Continuing the trauma with ‘psychiatric help’ is not fair. Recognize another human when you see them.

This is an interesting review, and highlights the importance of considering the traumatising impact of psychosis. However, a recent methodological review of the area highlighted a number of difficulties with the assessment process in these studies, and it is therefore difficult to establish the prevalence of PR-PTSD based on these studies. It’s critical in clinical practice that we recognise the impact of psychosis and it’s treatment on people, however, a range of traumatic stress reactions can be confused with PTSD, and a concern is that invalid application of the PR-PTSD diagnosis could lead to people being offered tf-CBT when other approaches may be more useful.

Please see http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3402/ejpt.v7.32095.

Well I think you may be threatened with death if your voices repeatedly tell you to kill yourself. Wouldn’t that count and it’s not uncommon.

Thanks Prof Rose, I very much agree the experience you describe would be traumatic, and is common and can understandably can lead to traumatic stress reactions. The question is what is the nature of this impact, and whether it is reflective of PTSD or another post-traumatic reaction. PTSD is characterised by memories of past experiences which occur in the ‘here and now’ and so have a sense of reliving – which distinguishes them from the vivid, emotionally intense intrusive memories that occur in a range of difficulties. In the example you describe, it would be important to explore with the person whether the threat of death is linked to re-experiencing memories (as in PR-PTSD), or a more general concern/fear about being killed based on their memory of what they experienced. Both are post-traumatic stress reactions and support should be given, however in the former evidence suggests the therapy approach should focus on reprocessing/exposure to the trauma memory (i.e. of the voice being threatening) whereas in the latter other approaches (e.g. supporting the person to feel safer in the here and now) may be prioritised.

[…] voices or seeing things. However, the relationship between these problems is poorly understood. Associations between PTSD and first episode psychosis have previously been discussed on The Mental Elf. Psychosis and trauma also often co-exist (Schafer […]

Hi, I have complex PTSD and psychosis. Am currently looking for literature to understand my symptoms. If anyone knows of any please contact me. Thank you it would be of great help.

I found this article because I was looking to find resources for people who were traumatized by their psychotic episode. During my episode, I felt as though I was being tortured by demons and secret government microwave weapons, all while being screamed at by this terrifying voice who sounded like James Earl Jones on steroids. This went on for months. Whether or not any doctor believes what I experienced was “real,” it was real enough to me. I feel like a torture victim. To this day, I can’t stand any sort of violence on TV or in the news. I’m hypersensitive to unkindness and cruelty towards people and animals, and while that is a positive trait to an extent, it makes it impossible to live in this world. You must have at least a little hardness in order to make it through the day. Exposure to unkindness is crippling.

[…] Croft, J. (2017, August). The trauma of psychosis: high rates of PTSD in first episode psychosis. The Mental Elf. Retrieved from here. […]

I was attacked in 1987, this caused PTSD and a psychosis. Today i’m diagnosed with schizo affective disorder.