This is the third in a series of Mental Elf blogs produced in partnership with the British Journal of Psychiatry.

Lutgens, Gariepy and Malla (2017) take on a large piece of work with this systematic review and meta-analysis, which aims to provide a quantitative synthesis of the effectiveness of psychological and social treatments for negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Their aim is laudable.

Negative symptoms consist of poor motivation (anhedonia), reduced communication (impoverished speech known as alogia) and diminished affective expression. This results in poor social functioning and increasing isolation. Negative symptoms are notoriously hard to treat and cause individual suffering, contribute to poor quality of life, are related to poor physical health and significant carer burden.

NICE currently recommends clozapine and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for persisting (positive and negative) symptoms of psychosis and specifically art therapy for negative symptoms (NICE, 2014). The British Association for Psychopharmacology highlights the need for careful assessment and appropriate treatment of secondary negative symptoms (those negative symptoms that occur as the result of medication, depression or persistent positive symptoms) and recognises that the pharmacological treatment of primary negative symptoms is challenging; some evidence suggests clozapine is effective but there is little evidence to otherwise recommend second generation over first generation antipsychotics (Barnes et al, 2011). Thus it is clear that present pharmacological treatments for primary negative symptoms are limited and evidence for other interventions much needed.

The negative symptoms of schizophrenia contribute to poor quality of life, poor physical health and significant carer burden.

Methods

Using a pre-registered protocol and following PRISMA guidelines, authors systematically searched MEDLINE, PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Psych Info and the Cochrane Library databases for papers that investigated psychological or social interventions and reported negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Inclusion criteria for studies included:

- RCT design

- Investigating psychological or psychosocial treatment

- Report negative symptoms using a valid and reliable negative symptom measurement

- Had a sample with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or other non-organic psychotic disorder

Quality assessment was assessed from the critical appraisal checklist on standardisation of treatment, recruitment, sequence generation, allocation, concealment, comparability of groups, equality of care between groups, attrition, adherence and intention to treat analysis. 15 studies were rated as low quality, with full details included in supplementary tables.

Results

11,794 studies were initially retrieved and 4,150 citations screened after removal of duplicities. Pharmacological trials, reviews, case studies, qualitative studies and 5 non-English papers were excluded, with a final total of 72 papers included in the quantitative synthesis. For quantitative synthesis, studies were grouped in to 7 groups:

- 26 studies investigated CBT

- 17 studies investigated skills training (n=11), occupational therapy (n=3) and cognitive adaption training (n=2) or vocational training (n=1)

- 16 studies investigated neurocognitive therapy, including cognitive remediation (n=11), cognitive training (n=2), cognitive rehabilitation n=1), neurocognitive therapy (n=1) and cognitive enhancement (n=1)

- 10 studies investigated exercise therapy

- 7 studies investigated arts based interventions (fine art n=2 and music-based n=5)

- 6 studies investigated family based interventions

- 10 studies investigated other miscellaneous therapies

The main results were:

- Compared to treatment as usual (TAU), CBT, skills-based training, exercise and music treatments provided significant benefit, as measured by a statistically significant change in negative symptom score.

- Occupational therapy and cognitive adaption training also showed a modest effect, again driven by studies that compared interventions to TAU.

- A small number of studies compared an intervention to ‘active controls’, where the treatment group is compared to another group who have an alternative ‘active’ intervention and in these cases effects were smaller and often not significant. For example CBT, which has the largest number of studies, showed a Standardised Mean Difference of -0.34 (equivalent to a moderate effect) when compared to TAU, but when looking at studies with active control groups, no significant difference was detected as both experimental and control groups improved.

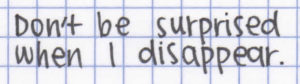

- Earlier treatment appeared more effective than treatment for those with chronic illness, but these effects lasted only as long as patients remained in treatment.

Some interventions provided significant benefits when compared to treatment as usual, but these benefits disappeared when compared with active control groups.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that psychological and psychosocial interventions have some utility in ameliorating negative symptoms in psychosis and should be included in the treatment of negative symptoms. They also state that more effective treatments for negative symptoms need to be developed.

Limitations

The authors acknowledge the limitations of this review: the heterogeneity was large, a funnel plot showed a potential publication bias to reporting positive studies and, most importantly perhaps, most studies were not designed to investigate the effects of intervention on negative symptoms specifically. The majority compared psychological intervention to TAU (a nemesis of all psychological intervention trials) and no studies differentiated primary from secondary negative symptoms, thus effects may indeed be related to treatment effects on the primary cause.

Commentary

One definitive conclusion to draw is that, whilst the authors are right to draw attention to this area of unmet need, we need more robust evidence with large, better-designed trials that focus on the effect of interventions for (primary) negative symptoms. We also need studies that report patient experience (qualitative research) and better understand what is a clinically significant change: Does improvement in diminished expression increase quality of life? Is ahnedonia the target negative symptom to treat? Many studies currently assess effects on symptoms as a whole, global functioning or quality of life and we need to understand more about the distinct contribution primary negative symptoms make, and what treatments are best.

However, NICE recommendations for art therapy, over other forms of psychological and psychosocial interventions, may need review, and indeed this has been highlighted previously (Kendall, 2012; Judge, 2014).

CBT should continue to be recommended for treatment resistant symptoms; evidence presented here suggests that potentially a wide range of options may be effective for negative symptoms; thus clinicians should also consider patient preference and availability of therapies.

As we’ve said before, NICE should review their recommendation for art therapy, over other forms of psychological and psychosocial interventions.

Links

Primary paper

Lutgens D, Gariepy G, Malla A. (2017) Psychological and psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms in psychosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2017, bjp.bp.116.197103; DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.116.197103 [Abstract]

Other references

NICE (2014) Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. Clinical Guideline 178, National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health.

Barnes TR. (2011) Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology (PDF). Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(5), 567-620.

Kendall T. (2012) Treating negative symptoms of schizophrenia. BMJ 2012;344 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e664 (Published 28 February 2012)

Judge J. (2014) Art therapy for schizophrenia: an effective add-on treatment? The Mental Elf, 27 Jun 2014.

Art therapy for schizophrenia: an effective add-on treatment?

Hi not sure about CBT for negative symptoms According to Jauhar et al 2014 BJPSYCH CBT had little effect on negative symptoms

There have been several studies and meta-analyses demonstrating robust clinical improvements of negative symptoms using rTMS, iTBS, and deep TMS. Such neuromodulation techniques show a lot of promise in treating schizophrenia symptoms (positive and negative). In Israel and Europe, deep TMS is officially approved by health authorities as a treatment for negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Please spread the word so that those treatments can go mainstream!!!

[…] Psychosocial interventions for negative symptoms in psychosis […]