We came into psychiatry after data busted the dogma that psychoses affect all individuals equally, regardless of sex, race, or ethnicity (McGrath, 2006). Rather, a series of systematic reviews mapped out various gradients and contours in the epidemiological landscape (McGrath et al, 2008). The landscape was not flat. There were mountains, there were fields, and there were city walls.

It turns out, however, that our understanding of the epidemiology of psychoses was based on limited data. As with most things in life (think: the Pareto Principle), most of what we know about the epidemiology of psychoses comes from the findings of a minority of countries in the world. In the current paper by Morgan et al., the authors explore the relatively uncharted territories in the Global South (referring broadly to the regions of Latin America, Asia, Africa and Oceania consisting of more than 80% of the world’s population, which have contributed to fewer than 10% of the research in this area).

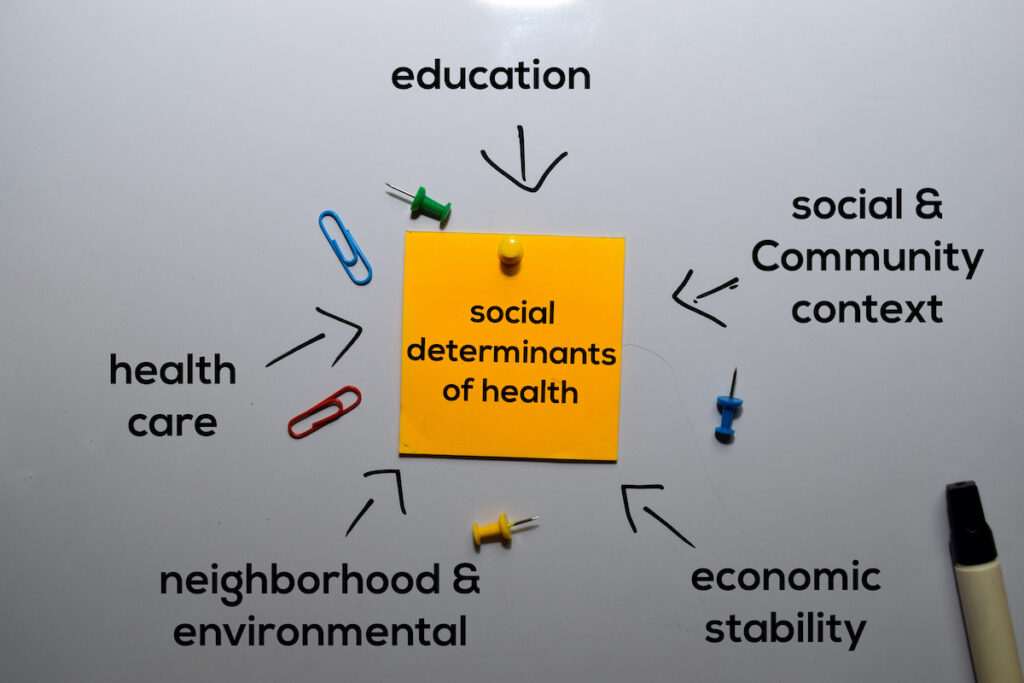

How can we genuinely understand psychoses, a disorder significantly impacted by diverse social and cultural contexts, if we ignore over 80% of the population of our planet? The International Research Program on Psychotic Disorders in Diverse Settings (INTREPID II) has been established to address this evidence gap. In the current study, the authors present the rates of untreated psychosis (as a proxy for incidence rates) in three countries (India, Nigeria, and Trinidad; interestingly, the catchment areas in the study all lie North of the Equator) in the Global South.

How can we genuinely understand psychoses, a disorder significantly impacted by diverse social and cultural contexts, if we ignore over 80% of the world population? INTREPID II study aims to provide answers.

Methods

The study estimated the incidence of psychoses by using the rates of untreated psychoses (cases) in three socioeconomically distinct places in the Great South ([1] Kancheepuram District, Tamil Nadu in India, [2] Ibadan, Oyo State in Nigeria, and [3] northern Trinidad). These catchment areas comprise around 500,000 adults (aged 18 to 64). The Program also obtained the population-based matched controls and information from the relatives of the cases.

The program used a multi-pronged approach to identify potential cases:

- Case-detection systems were established by mapping and engaging service providers and community informants. These were categorised into; (a) professional (i.e. mental health services), (b) folk (i.e. traditional, spiritual healers), and (c) popular (i.e. community informants).

- Shared understandings of “psychoses” were facilitated by the researchers giving materials that described experiences and behaviours characteristics of psychoses, using local terms and language.

- Regular check-ups were conducted between the researchers and members of the case-detection systems to identify potential cases.

- In rural villages in Kancheepuram and Ibadan, field workers engaged with community informants to identify potential cases.

Leakage studies were also conducted by rechecking service registers and completing final checks with mental health professionals, traditional and spiritual healers, and informants.

Once identified, the potential cases were screened using the Screening Schedule for Psychosis. All cases screened positive were approached to participate in INTREPID II.

For each participant in INTREPID II, the data on sociodemographic characteristics and symptoms (including the duration of untreated psychosis) were collated from cases, relatives, and clinical records (where available) with assessments conducted by researchers fluent in the local language.

The population at risk for each location was estimated using the most recent census data (2011 in India, 2010 in Nigeria, and 2011 in Trinidad and Tobago).

Results

The authors found many variations in data in the three settings.

Differences in case identification:

- In Kancheepuram (India), 268 cases were identified

- The majority (83.6%) of cases were identified by the popular sector,

- while the folk sector identified no case at all

- with the professional sector identifying the remaining 16.4%.

- In Ibadan (Nigeria), 196 cases were identified

- Just over half (51.0%) of cases were identified by the professional sector

- with 44.9% identified by the folk sector.

- The popular sector identified 4.1%.

- In Trinidad, 574 cases were identified

- Almost all (98.4%) of the cases were identified by the professional sectors

- with the folk sector and the popular sector identifying fewer than 1% each (0.9% and 0.7% respectively).

Differences in demographic and clinical characteristics:

- The sex- and age-standardised rates of untreated psychosis were highest in Trinidad (59.1 cases per 100,000 person-years), followed by 20.7 cases per 100,000 person-years in Kancheepuram and 14.4 cases per 100,000 person-years in Ibadan. Compared to Kancheepuram (the reference site), the adjusted incidence rate ratio was 3.03 in Trinidad (95% confidence interval 2.62 to 3.51) and 0.71 (0.59 to 0.85) in Ibadan.

- Both the age of detection and onset were significantly younger in Trinidad (mean of 32.7 and 28.9 years, respectively) compared to Ibadan (35.3 and 32.1) and Kancheepuram (41.8 and 35.1).

- The majority (96.4% in Kancheepuram, 94.4% in Ibadan and 87.2% in Trinidad) of cases had the onset of psychoses after the age of 18.

- There were more male cases in Ibadan (52.6%) and Trinidad (59.1%), but not in Kancheepuram (42.5%).

- Ethnic diversity was evident in Trinidad (African, Indian, and mixed) but not in the other two sites.

- The median duration of untreated psychoses was the shortest in Trinidad (11.0 months) compared to 37.8 months in Ibadan and 55.6 months in Kancheepuram. Compared to Kancheepuram (the reference site), the adjusted incidence rate ratio for having a short duration of untreated psychosis (defined as less than two years) was much higher in Trinidad at 7.68 (95% confidence interval 6.01 to 8.92) and marginally higher in Ibadan at 1.32 (0.98 to 1.77).

- In Kancheepuram, there were comparable proportions of cases diagnosed with schizophrenia (47.0%) and psychosis not otherwise specified (41.8%). In Ibadan, just over half (51.0%) of cases were diagnosed with schizophrenia, followed by psychosis not otherwise specified (17.9%) and manic disorder (13.3%). In Trinidad, only 38.5% of cases were diagnosed with schizophrenia (although it was still the most common diagnosis), followed by brief psychosis (17.1%), depressive psychosis (13.9%), and manic disorder (11.2%). Strikingly (to us at least), very few cases met the diagnosis of psychosis associated with substance use (0.4% in Kancheepuram, 0% in Ibadan, and 3.7% in Trinidad).

Diversity in the incidence of psychoses was found in India, Nigeria and Trinidad.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

Findings of this cohort study add to research that suggests core aspects of psychosis are shaped by historic, economic, and social context. It follows that we can only fully understand the etiology, manifestations, and outcomes of psychoses – indeed the very nature of psychoses – if we research psychoses in context.

They also highlight the importance of grounding the development and delivery of services in locally-contextualised knowledge, all the while tailoring care to the individual while balancing this out with providing care to populations in a real-world setting.

The authors concluded: “We can only fully understand the etiology, manifestations, and outcomes of psychoses if we research psychoses in context”.

Strengths and limitations

INTREPID II has implemented an impressive and comprehensive multi-pronged approach to case identification. It is a similar approach one would and should take in assessing culturally and linguistically diverse peoples in our clinical practice, but the programme seems to have established a meticulous system.

The authors identified several limitations in the current study. The three main limitations reported were:

- Despite the comprehensive multi-pronged case identification system, it is possible that some cases were missed and the rate of missed cases differed significantly in each site (after all, everything else seems to differ in the three sites),

- Although consistent with the methodology employed in previous similar studies, the use of untreated psychoses as a proxy for incident cases may underestimate the rate in different sites especially given the significant differences in the duration of untreated psychoses in the three sites, and

- The use of projections from previous censuses to estimate populations at risk may lead to inaccuracies and distorted rate ratios. For instance, the rate is likely to have been overestimated in Ibadan, where projections were available only in 2016.

The comprehensive multi-pronged approach of the INTREPID II study to case identification was impressive.

Implications for practice

The cool thing about psychiatric epidemiology is that it is like the academic equivalent of charting a new territory. Reading well-conducted epidemiology articles feels like reading Captains’ logs from centuries gone by. You explore and imagine different contours of the land. You climb the highest mountains, you run through the fields, and you scale the city walls. You try to find potential risk factors that are hopefully modifiable.

The diagnostic conceptualisation of psychoses has varied and evolved over the centuries (Jablensky, 2010). The findings from the current study further support the notion that there are prominent variations in the incidence of psychoses in different sites – even within the Global South. Reading back on modern classics in psychiatric epidemiology, we reflected on some uncomfortable questions to ponder: Do we spend so much time thinking about the very concepts of psychoses in psychiatry because we have not progressed much in providing effective treatment? Does it matter what historical, economic, and social factors contribute to the expression of the disease if we knew how to make the symptoms go away (this may be what all in the healing professions ask themselves)?

As we progress in our psychiatric epidemiological journey, we need to know where True North lies and make sure the Compass we use is pointing towards it. Psychiatry should aim to do more than describe and categorise psychological distress and epidemiological risk factors. We need to remind ourselves that we explore because we are looking for something meaningful. In asking these questions and seeking answers, we must ground ourselves in locally-contextualised knowledge. But we suspect that we still haven’t found what we’re looking for.

The findings further support the notion that there are prominent variations in the incidence of psychoses in different countries.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Morgan, C., Cohen, A., Esponda, G., Roberts, T., et al. (2023) Epidemiology of Untreated Psychoses in 3 Diverse Settings in the Global South: The International Research Program on Psychotic Disorders in Diverse Settings (INTREPID II). JAMA Psychiatry 80 :40–48.

Other references

Jablensky, A. (2010) The diagnostic concept of schizophrenia: its history, evolution, and future prospects. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 12: 271 – 287.

McGrath, J. (2006) Variation in the Incidence of Schizophrenia: Data Versus Dogma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32: 195 – 197.

McGrath, J., Saha, S., Chant, D., Welham, J. (2008) Schizophrenia: A Concise Overview of Incidence, Prevalence, and Mortality. Epidemiologic Reviews 30: 67 – 76.

Photo credits

- Photo by Jen Theodore on Unsplash

- Photo by Maud Slaats on Unsplash