Personality disorder often represents something of an enigma: In one way the diagnosis itself can be seen as deeply stigmatising; while the notion of precisely what is disordered, (that is – what is personality?) raises some profound questions.

During my own clinical practice some of the people I’ve been most deeply personally affected by are those who have received these diagnoses; hence my decision to focus on this group of people’s experiences in my PhD research. Unfortunately if psychiatry is the Cinderella specialty of all the medical specialties then personality disorder is unfortunately likely best compared to the lost glass slipper.

So, it was with some surprise that I came across a series in The Lancet devoted to Personality disorder with no less than three consecutive papers (Tyrer et al, 2015; Newton-Howes et al, 2015; Bateman et al, 2015). These are not research papers, but position statements produced by individuals with extensive experience of personality disorder research and treatment. Search strategies are only loosely described and I am not going to critique the methodology used here, simply instead focussing on their content and then offering some brief closing thoughts.

Classification, assessment, prevalence and effect of personality disorder (Tyrer et al, 2015)

Assessment and Diagnosis

Current diagnostic classification systems approach the diagnosis by first offering a general definition of personality disorder and then going on to offer a series of categorical ‘types’ of specific disorder. In keeping with other diagnoses the received diagnosis would then purportedly inform treatment options. This approach had a number of limitations:

- Few people are formally assessed in relation to personality. Those that are often receive many co-morbid diagnoses that lead to complicated explanations and treatment decisions.

- Most diagnoses are never used. The commonest diagnoses given are Borderline Personality Disorder, Dissocial Personality Disorder, or simply ‘Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified’.

- Few people consider personality to be distributed in terms of categorical ‘types’. Instead personality is thought to exist on a spectrum. Why then should we assume that ‘disordered’ personality should be categorically defined?

The commonest diagnoses given are Borderline Personality Disorder, Dissocial Personality Disorder, or simply ‘Personality Disorder Not Otherwise Specified’.

The working group for personality disorder within DSM-5 did make efforts to change this process; proposing a ‘hybrid’ categorical and spectrum model that was ultimately voted down by the publication advisory board.

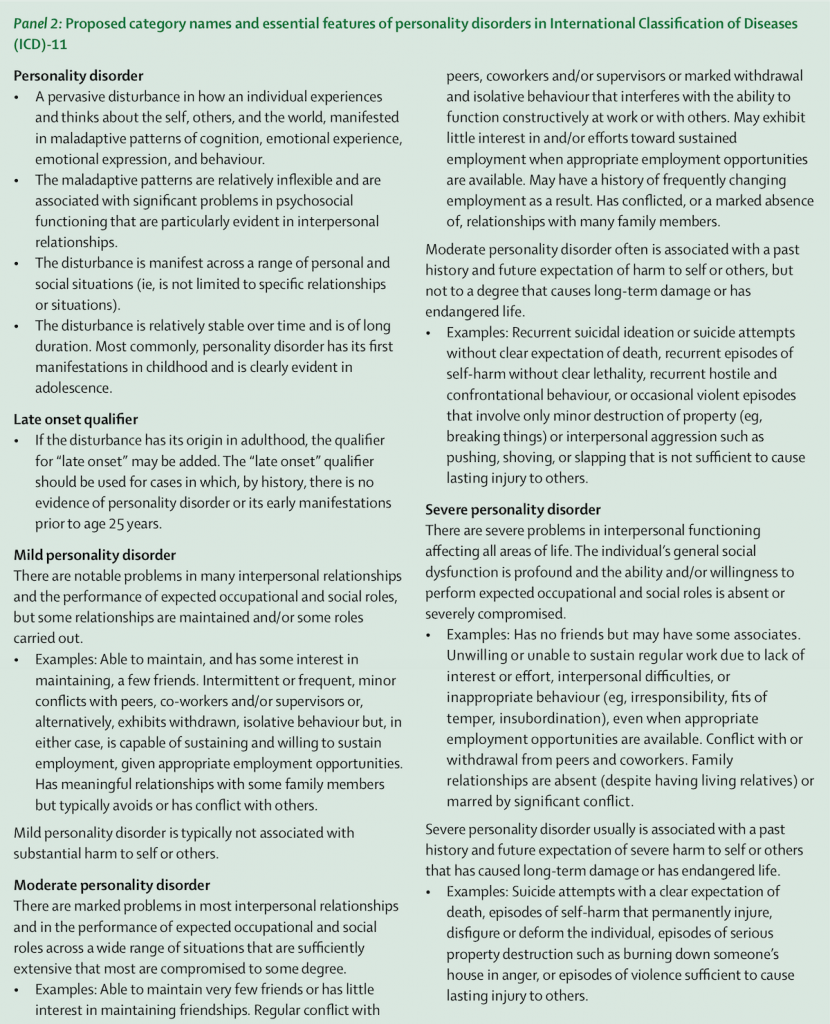

The working group for ICD-11 has also proposed changes: They suggest that all types be removed with the exception of the primary ‘Personality Disorder’ diagnosis that should then be classified according to severity in terms of its impact on the individual.

Finally five domains may be used to further specify the individual’s experience. The authors (Tyrer et al, 2015) propose that this new classification system would provide an easier means of reaching a diagnosis, with the domain assessment being necessary only in ‘specialist settings’.

Prevalence and implications

The authors say that little research has been possible to assess the prevalence of personality disorder with current ‘best guess’ estimates, placing the number at 4-15% in Europe and North America with only one international study having been conducted which placed the estimated prevalence at 6.1%.

The prevalence is estimated to be higher in psychiatric practice; approximately 25% in outpatient settings and 50% in inpatient settings.

The highest levels are estimated to be found in prison populations where up to two-thirds of the population may have a diagnosable personality disorder.

Personality disorder is described as having an impact for all medical practitioners; with an estimated loss of life expectancy of 18-19 years for men and women respectively. Other forms of mental distress are recognised as being harder to treat in the presence of personality disorder.

It’s estimated that personality disorders may be most prevalent in the prison population.

Personality disorder across the life course (Newton-Howes et al, 2015)

Stability and change

Personality has classically been viewed as being fixed in adult life following its development during childhood and adolescence. However, research highlighted by the authors challenges this assumption, showing that some features of personality appear relatively stable throughout life, but that others undergo a more fluctuant development. What seems most likely then is that the rate of change of personality development slows throughout life.

In adolescence

Current diagnostic classifications acknowledge the origin of personality disorder in early life; but also recommend caution in its diagnosis in adolescence. However, as described above, there is evidence of a stability of personality through childhood and adolescence that may include personality difficulties. The authors comment on the fear of clinicians in diagnosing such disorders in adolescence with a risk of stigmatisation. However, they also recommend that, given the existence of appropriate treatment strategies, withholding the diagnosis may be problematic.

In later life

The authors bemoan the lack of data available regarding the experience of personality disorder in later life. However, they cite evidence that personality disorder continues to cause distress in later life and is associated with functional loss, poor health and premature mortality.

A life course approach

This second paper ends with a call from the authors for the adoption of a diagnostic system that adequately reflects scientific understanding and the whole of the life course experience. They argue that such an approach is essential and that particular focus is given to early detection, prevention and amelioration in adolescence.

Treatment of personality disorder (Bateman et al, 2015)

The current evidence base for the treatment of personality disorder is unclear with varying claims made for the efficacy of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. In this paper, the authors open with a critique of the current evidence base:

- Outcome measures: The core construct features of personality disorder are difficult to define and measure, as such an excess of varying outcome measures exist that do not adequately capture pertinent experiences

- Meta-analysis: Any meta-analysis attempt is necessarily limited by the above point. How can varying outcome measures be combined together in a satisfactory way when they focus on such distinct domains?

- Borderline personality disorder: Most research focuses on the experience of those with a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. Other diagnoses are relatively neglected

- Clinical trials: A systematic review by Duggan and colleagues highlights the low population within clinical trials, short treatment durations and poor length of follow up. Almost all pharmacotherapy trials are industry funded and for psychotherapy most are conducted by researches affiliated with the treatment approach (or manual) used in the trial. The risk of bias in the evidence base is therefore considerable

- Comorbidity with other diagnoses is the rule in personality disorder and this fact is often poorly accounted for in clinical research

The dearth of reliable evidence about the treatment of personality disorders makes patient care a real challenge.

Despite this pessimistic appraisal there is indication for some optimism as there is evidence that some treatment approaches are likely effective.

Based on their review and experience, the authors make a series of recommendations:

- Psychological treatment

- Offer structured (manualised) treatments that focus on working in collaboration with patients, allowing them to assume control over their experience

- Therapists should be active, responsive and validating during treatment

- The supervision of therapists is essential

- Pharmacotherapy

- Should be offered only as part of a tailored psychosocial intervention

- Should be specifically focussed, time limited and removed after crisis symptoms or situations have resolved

- Research

- The varying psychosocial treatments available should be synthesised, based on improved understanding of aetiology and formulation

- Treatment planning

- Short, targeted interventions within sequenced treatment plans may be more beneficial than delivery of intensive programmes

The authors recommend structured psychotherapies that focus on working in collaboration with patients, allowing them to assume control over their experience.

Conclusions and reflections

The study of personality disorder has come a long way in the past 10 years, and the publication of this series of papers in a high impact journal such as The Lancet is one indication of this. That such mainstream medical attention is focussed on the experience of those who receive the diagnosis is heartening. However as each of the authors in the papers highlights, there is still some way to go.

I just wanted to add a couple of my own thoughts to those described above:

- Diagnosis: The diagnosis of personality disorder remains problematic in its very nature and unfortunately the atheoretical approach (i.e. without a theoretical basis) of systems such as DSM-5 and ICD-11 cannot, in my opinion, address this

- Heterogenous experience: Those receiving the diagnoses currently represent a highly varied range of experiences. Will the new proposals within ICD-11 be able to reflect this? Domain based continuous scale assessment can, in theory, offer an infinite amount of variation within the diagnosis, but as the authors comment, how many outside of specialist services will receive such detailed assessment? Do we risk simply combining a large number of people under one diagnostic umbrella?

- Diagnosis and normalisation: A large number of people draw some sense of comfort, normalisation and communal identity from diagnoses such as Borderline Personality Disorder. If these diagnoses are abolished, where does that leave these people?

- Formulation, formulation, formulation: A leitmotif in many of my blogs on this website has been the importance of an idiographic formulation-based approach to assessment and treatment. I’m not going to repeat this at length here but simply to say that, if ever there was a need for an individualised approach, ‘personality disorder’ is surely that case? Diagnosis is often cited as being essential to aid communication and appropriate care planning, but how much clarity does this diagnosis yield? Can we not adopt clinical and research paradigms that adequately support a formulation-based approach to care?

What remains important is that this group of experiences are finally receiving the spotlight attention they need. It is impossible to do justice to the complexity here (particularly with a [benevolent – Ed.] editor snapping at my heels on word count) but this is a conversation starter. Bring on the debate.

We’d love to hear your views on personality disorders and these new Lancet papers. Use the comment feature below or drop us a line via Twitter.

Links

Primary papers

Tyrer P, Reed GM, Crawford MJ. (2015) Classification, assessment, prevalence, and effect of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 717–726. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61995-4 [PubMed abstractct]

Newton-Howes G, Clark LA, Chanen A. (2015) Personality disorder across the life course. The Lancet, 385(9969), 727–734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61283-6 [PubMed abstract]

Bateman AW, Gunderson J, Mulder R. (2015) Treatment of personality disorder. The Lancet, 385(9969), 735–743. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61394-5 [PubMed abstract]

Personality disorder series. The Lancet (articles available free of charge: requires registration)

Other references

Duggan, C., Huband, N., Smailagic, N., Ferriter, M., & Adams, C. (2008). The use of pharmacological treatments for people with personality disorder: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Personality and Mental Health, 2(3), 119–170. doi:10.1002/pmh.41 [Abstract]

I’ve written a letter to Peter Tyrer representative for ICD11 PD here http://t.co/Xp4her4DON it’s stigmatising I’m waiting for a reply …

Also ICD11 PD is stigmatising I’m wondering why we have no support from @MindCharity or @Rethink_ http://t.co/Xp4her4DON I’m not violent

Great blog Andrew. While I think the diagnostic characteristics work better I think the severity ratings are problematic within a diagnostic framework. For the same reasons highlighted by Newton-Howes et al, the severity of behaviours can fluctuate and vary over time. In addition Dr Paul Moran has highlighted that although behaviours may appear to mediate in later age, in practice this could represent a reduction in negative behaviours but not necessarily an increase in positive behaviours hence the continued negative impact on quality of life and lifetime mortality.

I also share you concern that the ‘mild’ category is could pretty much function as a catch all.

In practice, the severity features appear to function better for treatment purposes as opposed to diagnostic.

Finally, the focus on adverse behavioural characteristics has contributed greatly to the stigma of PD. The inclusion of ‘willingness’ to work as a characteristic of PD severity feels overtly judgmental, not reflected in any other mental heath diagnoses and difficult to establish given the complexity of the context which influences this.

Hi, interesting article(s), although I have only read Andrew’s so far, but will read the Lancet articles.

I may well be wrong but aren’t we really still doing what we have always done with people who are given this diagnosis? Sure services have move forward and treatments evolved over time, but I don’t think we are going about it in the right way. We are still looking at the ‘end result’ and we are not looking at the core cause(s). How does a personality disorder develop? Trauma(s) for the most part – pure and simple. Early Developmental Trauma(s) and subsequent trauma(s). Adverse childhood experiences (ACE’s). And what do we do? Re-traumatise. By giving a label (diagnosis), by working for the client (we know best) as opposed to working with. Formulation, absoloutely. Help the client understand why they think, feel, behave the way they do (when bad things (ACE’s) happen to good people, work together to join the dots. If we had had some of the experiences many of our clients have had – where would we be now? On a ward with a diagnoses of BDP and no doubt multiple other diagnosis during our decades of involvement with psychiatric services (not to mention the poly-pharmacy that goes with it). Are symtoms really symptoms, or are they adaptations – how people adapted to cope, to survive (ACE’s), but not thrive. Bessel van der Kolk (psychiatrist) says a mis-diagnosed patient is a mis- treated patient and I couldn’t agree more.