It is increasingly recognised in society today that mental health is an important aspect of health, and increasingly the public values mental health equally with physical health.

It is about time this societal change takes place; we have known for a while that about 1 in 4 people will experience a mental health problem each year (McManus et al, 2009) and that nearly 75% of adults who had a psychiatric disorder were diagnosed with a mental health problem before the age of 18, most often conduct disorders (Kim-Cohen et al, 2003).

People transition in and out of periods of mental ill health throughout their whole life. The aim is not only to prevent and treat mental illness, but also to overcome the challenges that mental ill health brings throughout the lifespan; allowing people to live better lives.

For research, challenges are big, possibilities are real, innovation proliferates, and transformative discoveries are within reach. However, the translation of research findings into practice is slow, the impact on policy is insufficient, and evidence indicates that research funding is lagging far behind this recent change in population awareness.

The translation of research findings into practice is slow, the impact on policy is insufficient, and evidence indicates that mental health research funding is lagging far behind.

Mental health research: still not getting its fair share

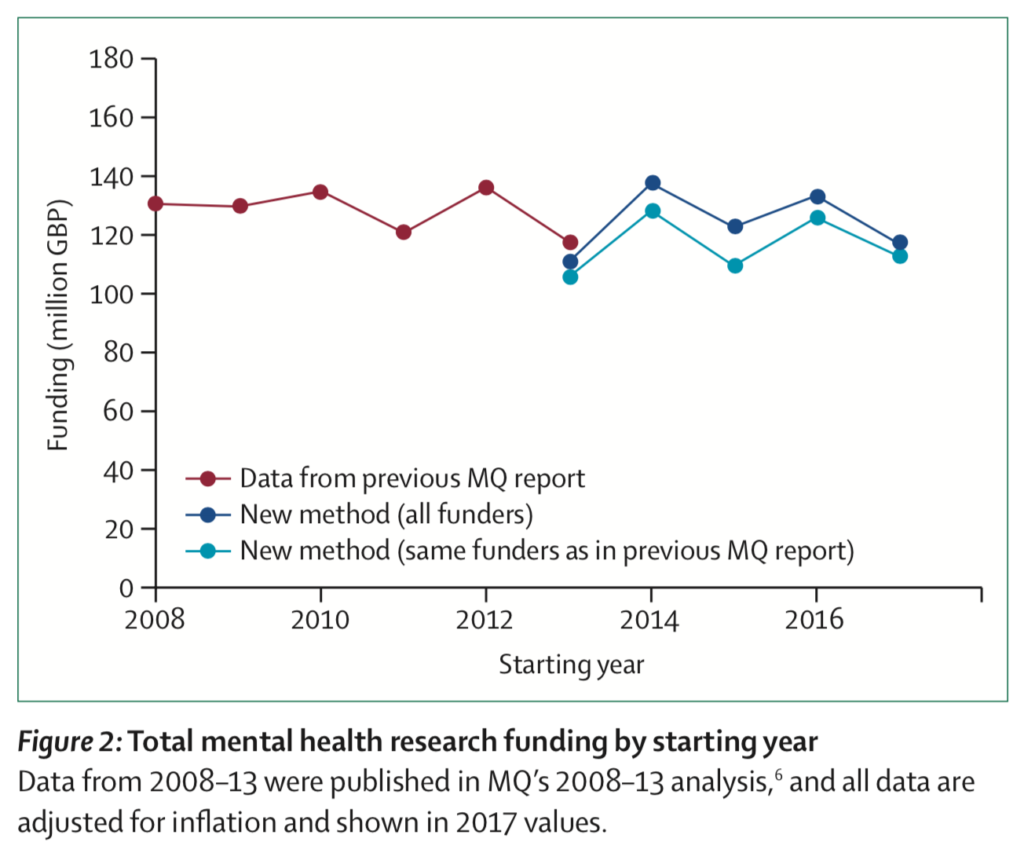

The mental health research charity MQ: Transforming Mental Health have today published a report compiling research grants awarded by UK major funders between 2014 and 2017 (MQ Mental Health, 2019). It suggests a classification system for a better and clearer analysis of recent investments in mental health research. It will probably not be a surprise that mental health research is underfunded relative to both other areas of health sciences and to its burden on society.

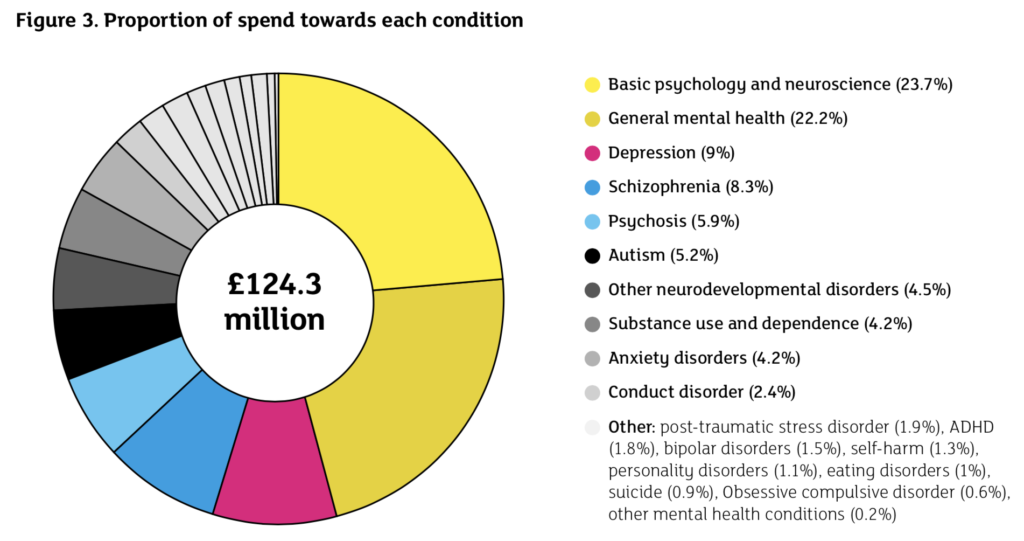

- MQ reports that across 4 years (2014-17), an average of £124 million was spent on mental health research compared to £612 million for cancer

- This means that 25 times more was spent on research per person with cancer than was spent on research per person with mental illness.

The economic impact of mental illnesses on society is considerable with an estimated £100 billion per year. The take home message here is not that mental illness is more important than cancer but instead, that given its burden on society, mental health research should receive its fair share of investment. It will also not be a surprise to read that mental health research funding has remained unchanged for the past decade, with a comparable spending of £115 million on average per year between 2008 and 2013.

Mental health research funding has flatlined over the last decade. In 2014-17, mental health research received 25 times less funding (per person affected) than physical conditions such as cancer.

Where does the money go?

The MQ report has a new way of classifying and presenting research funding (by mental health conditions, by type of research, by type of funder, and by research organisation), which brings up some surprising findings:

Mental health conditions

- Depression is the most common mental health problem in the UK and it receives the biggest share of funding awarded (£11 million per year), followed by schizophrenia, psychosis, autism and anxiety

- Self-harm, ADHD, personality disorders, and eating disorders have been neglected.

Many life-threatening mental health conditions remain largely ignored by research funders.

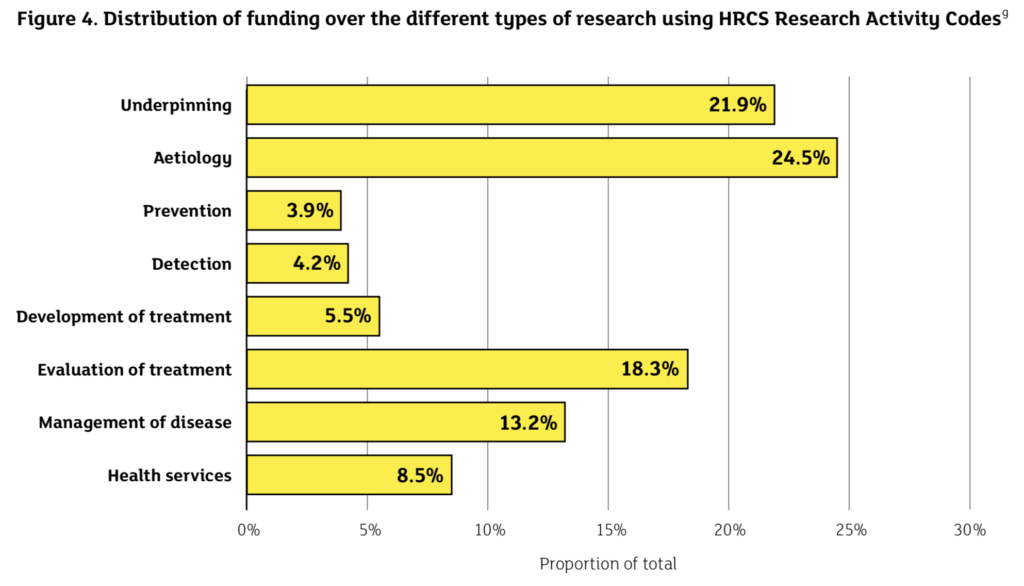

Types of research

- Nearly half of funding supports research on the underpinning and aetiology of mental health

- Detection, prevention, and development of treatments each get about 5% of the total funding.

We hear a lot about preventing mental illness these days, but this narrative is not reflected in research funding.

Sources and destinations for funding

- Government funders are the most supportive of mental health research (with 67% of the total investment)

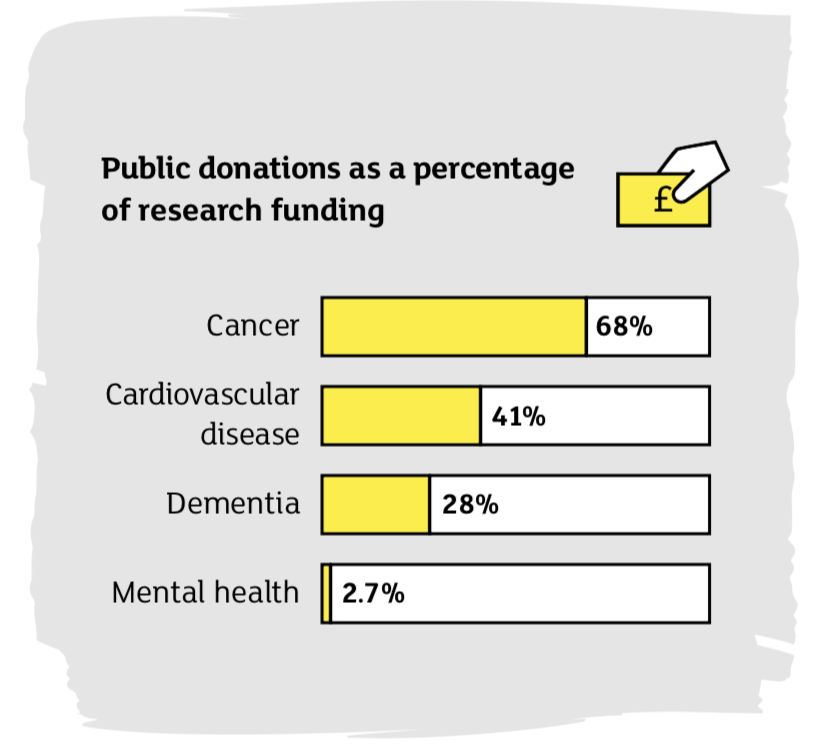

- Only 3% of funding came from charity fundraising, which is tiny compared with cancer (68%), cardiovascular disease (41%) and dementia (28%)

- Funding was shared across 250 UK institutions (universities, institutes and NHS trusts), but 3 institutions (University of Oxford, University College London and King’s College London) between them received 35% of the total funding, which equates to over £43 million per year.

Why does the general public not donate to mental health in the same way as they do to cancer, cardiovascular disease and dementia?

Priorities for future funding

To say that there is an urgent need for more research funding to face the challenges posed by mental ill health is an understatement. In the current political and economic climate, one option is to identify key research priorities to allocate the limited resources available for the mental health crisis. However, we must keep on demanding more funding for mental health research from the government and from other funders, as a priority on a similar level to physical health. We should also strengthen, or in some instances change, our approach to research. For example, mental health funding needs to continue:

- Supporting a long-term vision while addressing short-term priorities, and ensure both are adequately funded. While 26% of funds went towards research on children and young people, funding for research on prevention is lacking. Identifying determinants of mental ill health (social, genetic, or biological) and developing interventions to support children and parents will provide long-term benefits as well as changing policy and practice. Funds are also needed to address priorities in the field – situations that need addressing now to manage the current crisis: research on effective treatment, self-harm and suicide among young people, mental health in prisons and among homeless people to name only a few.

- Building and maintaining a diversified and balanced portfolio of mental health research while mirroring most prevalent conditions across the lifespan and considering the most impactful disorders for prevention (e.g., conduct disorders).

- Generating more interdisciplinary research to reduce silo work. The creation of UKRI that linked up the research councils and the recent investment in 8 Mental Health Networks are good examples of this practice. Not one discipline will have the answer for the challenges mental health problems bring. We may have a chance if we work together.

- Requiring partnerships across sectors so mental research is connected to and influenced by those who experience mental health problems first hand, including service users and charities delivering services.

- Developing better methods for measuring mental (ill) health, evaluating economic impact, and accessing (new forms of) data.

- Widening the focus to include factors that are satellites to mental health problems for example stigma, social isolation and loneliness, access to care and sleep problems that can exacerbate mental health difficulties and be obstacles to effective treatment.

- Closing the gap between research discoveries, new clinical practices and treatment. This is especially important to identify the best ways of helping children, young people and families, so that they can benefit from mental health research.

- Championing a strong and growing mental health workforce in the UK. This covers various areas including research but also mental health professionals such as nurses and teachers. We need a strong focus on early career researchers to attract and retain the brightest talents in the UK.

- Translating research discoveries into meaningful changes in policy. This could start with involving policy makers in our research programmes.

- Anticipating the next challenges and priorities for mental health research by working with the services users, charities policy makers, professionals, and academics in the UK and abroad.

Cross-disciplinary working is a particular focus of the 8 new UKRI-funded Mental Health Networks.

Partnerships, awareness and innovation

Some of these ideas are not new and have been highlighted in the cross-disciplinary mental health research agenda (PDF) published by UKRI in 2017. With MQ’s ambition for change and as a community of advocates for mental health, we can also think of new ways to fund mental health research. Partnerships across various funders is a good way forward and will also support interdisciplinary research. Greater mental health awareness may generate greater public and philanthropic donations, but we need a framework around whether this is on an institutional, charity or funder level. We can support a loud and bold mental health awareness campaign that not only appeals to the general population but goes deep to reach the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups of people who need knowledge and education about mental health. It is also our responsibility, as a community of mental health researchers, to propose the best and the most innovative research projects that are at the forefront of science.

We urgently need more funding to make a real impact and transform mental health through research. The MQ campaign says it is time to give a **** about mental illness. I would say it is time to give more funding to research mental illness.

It is also our responsibility, as a community of mental health researchers, to propose the best and the most innovative research projects that are at the forefront of science.

Conflict of interest

Louise Arseneault is currently ESRC Mental Health Leadership Fellow and her role includes providing intellectual leadership and strategic advice in the priority area of mental health. It is a broad agenda including engaging research communities, promoting collaborations, advocating for mental health research, championing the co-design and co-production of research and providing advice to the ESRC and other research councils.

Disclosure

The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and not the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC).

Links

Primary paper

MQ Transforming Mental Health (2019) UK Mental Health Research Funding 2014–2017.

Other references

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R. (2009) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. The NHS Information Centre for health and social care.

Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. (2003) Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 709-717.

Woelbert E, Kirtley A, Balmer N, Dix S. (2019) How much is spent on mental health research: developing a system for categorising grant funding in the UK. The Lancet Psychiatry. Published Online February 26, 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30033-1

UKRI (2017) Widening cross-disciplinary research for mental health (PDF).

Photo credits

- Ravi CC BY 2.0

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Photo by Alex Iby on Unsplash

mental health research is in a negative spiral of being fragmented, having few good people to pitch, and of having funders and other health bodies packed, at both exec at non-exec level, with people from physical (not mental) health backgrounds.

the way to break through is to establish critical mass; a ‘Crick 2’; for mental illness research.

Thank you John I could not agree more. This is my charity’s Manifesto to End Mental Health Research Under Funding

1. The Miricyl Principle – mental health funding and funding into any illness, should be allocated in line with the human (burden of disease) and financial (cost of illness) impact of mental illness and other illnesses on society

2. The Bank of England Principle – when the Bank of England announces a change in interest rates it often adds commentary that costs it nothing but gives the markets more certainty. The government needs to announce funding of mental health research at the level of its impact on society and that it will remain at that level this will attract new researchers and increase ‘capacity’

3. The Department of Education Principle – in order to attract new maths and science teachers the Department of Education currently offers tax free incentives, over and above a salary, of up to £32,000. These incentives should be offered to potential mental health researchers at appropriate levels, until no longer necessary.

4. The IBM Principle – Make the incentives in dual funding from the Higher Education Councils more equitable or just scrap it completely. Currently universities spend income where they believe they have most to gain financially not where is best for society

5. The Olympic Principle –UK Sport invested £500m+ between 2000-2012 and the average Olympic medal tally doubled. UK Sport did not ask the athletes to double their medals tally and then offer them funding if they achieved this. This is what is happening in mental health research. It’s a Mexican stand-off. The government needs to take the lead in 1-3 above

6. The Accounting Standards Principle – UK government funders calculate illness spending on different bases, if at all. Accounting standards to calculate research funding by illnesses should be harmonised across all government departments and the UK, Wales and Northern Ireland, as in Scotland, should calculate their own burden of disease and cost of illnesses should also be calculated

We have campaigned and petitioned for equitable funding and the governments in England, Scotland and Wales have all dug their heels in. As a last resort we have now got to the point of making a legal challenge to UKRI’s funding. If you would like to read about it please take a look and feel free to share the page. https://www.crowdjustice.com/case/discrimination/

or please get in touch alexconway@miricyl.org

[…] Mental health research funding: we are still not getting our fair share […]