She is so underweight you wonder how she can still be alive. Her family is exhausted. The team has tried everything to help her recover. She is still convinced she is enormous. Every meal makes her angry, distressed and tearful. Surely there must be something else the doctor can offer?

On the face of it, the arguments for prescribing an antipsychotic medication might seem persuasive. After all, the beliefs some patients have about their body size can seem like delusions; plus, antipsychotics make people gain weight – for others this is a troublesome side effect; here, perhaps, it’s the solution.

So is an off-license prescription of an antipsychotic a reasonable thing to try? What does the scientific literature have to say?

Well, this paper (Dold et al, 2015) is a meta-analysis of all the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of second generation antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone; which are licensed to treat psychosis) in treating anorexia nervosa to date, so it seems like a good place to start.

It’s worth noting that the studies don’t address questions about whether SGAs might be beneficial in managing comorbid illness, or for one-off use in extreme distress, they are just concerned with whether they are effective treatments for anorexia nervosa.

Antipsychotics are increasingly administered to achieve weight gain in patients with anorexia nervosa. But is there any evidence to support this practice?

Methods

The authors have used an appropriate search strategy (based on that made for the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry Guidelines for the Pharmacological Treatment of Eating Disorders) to find RCTs comparing second generation antipsychotic (SGA) medication against placebo or no treatment for anorexia nervosa. They searched a range of databases using appropriate terms, and get a gold star for making attempts to get hold of unpublished studies from all SGA manufacturers.

They clearly state that the primary outcome they were investigating was weight gain from baseline to endpoint of treatment, with secondary outcomes of mean changes on two scales used to measure eating disorder pathology. Where possible, they used intention to treat data.

Statistical methods for comparing control and treatment groups, estimating effect size and looking for publication bias were appropriate. They planned several sensitivity analyses to see whether effects held for different sub-groups.

The primary outcome of interest in this meta-analysis was weight gain from baseline to endpoint of treatment.

Results

The authors managed to track down a total of 7 RCTs including 201 patients:

- Four trials (112 patients) examined olanzapine

- Two quetiapine (48 patients)

- One risperidone (41 patients)

The trials lasted 8-12 weeks, and patients had an average age of 24 (two trials were of under-18 year olds). The vast majority of patients were female (98.5%) and the average starting BMI was 16.3.

Treatment occurred in various different settings and in five studies participants were required to participate in a standard treatment program.

Quality of Trials

Five trials used appropriate randomisation; only four adequately concealed allocation. Drop-out rates varied from under 10% to over 25%.

Headlines

- The main result that there was no difference between the SGA group and control group in terms of change in BMI (Hedges’ g = 0.13 (95% CI -0.17 to 0.43), p = 0.4)

- Looking at the SGAs one at a time found no differences between treatment and control groups either

- Nor did any of the sensitivity analyses, or either of the measures of eating disorder pathology

- There was no evidence of any publication bias.

This meta-analysis finds that antipsychotics don’t lead to weight gain or improve eating disorder symptoms in patients with anorexia nervosa.

Strengths and limitations

The research literature seems pretty clear cut to me. Despite looking hard, this meta-analysis comes up with no evidence that SGAs work in the treatment of AN. They don’t lead to weight gain, and they don’t improve eating disorder symptoms, as measured by validated questionnaires.

Three of the authors disclose having served on drug company advisory boards or received travel grants and speaker’s fees from drug companies. If this biased them, presumably it would be in favour of finding an effect of drug treatment; in fact, they conclude: “[SGA’s] cannot be regarded generally as an evidence-based treatment model”.

The authors suggest this this lack of effect may be because trial patients were noncompliant with drugs that they knew might lead to weight gain; but this would be a “real world” problem with them too. They also suggest that subgroups of patients may benefit: however, this suggestion is based on a subset of participants from one trial, which was not sufficiently powered to make this comparison.

Potential side effects of treatment

The authors go on to state that “potential benefits of a pharmacotherapy in anorexia nervosa should be thoughtfully weighed against the possible risk of unwanted effects”. This seems to me to skim over the potentially problematic side effects of SGAs in this group of patients.

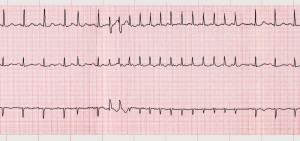

I would be particularly worried about the effects on the heart. Sorry to get technical, but there’s a risk of “QT interval prolongation” (it’s an ECG thing) in anorexia nervosa, and also with SGAs, and with low blood sugar. That may sound unnecessarily obscure, but having a prolonged QT interval can lead to the heart going into abnormal rhythms, which can lead to cardiac arrest and death. I don’t think we know exactly how big the risk is for this group of patients.

However, we do know that anorexia nervosa has a high mortality, which is not entirely explained by increased rates of death by suicide (Arcelus et al, 2011); and this (Wu et al, 2015) large population study finds that antipsychotic use is associated with a 50% increase in the rate of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Weigh thoughtfully, everyone.

Antipsychotics are associated with an increase in ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death; adverse effects that are worrying for everyone, but especially patients who are already dangerously underweight.

I am a bit confused by some of the authors’ maths – I’ve gone back to the original studies and as far as I can see the total N (number of patients in the study) is 195 not 201 (not sure where those extra 6 patients have popped up from). They also skim over the numbers lost by some studies failing to provide intention to treat data; I think this is why their main analysis uses 161 rather than 195 or even 201 patients. If you use only study completers, this tends to overestimate the likely effect of the drug being studied, because those doing better/having fewer side effects are more likely to continue treatment. This means that the true point estimate for difference between groups is probably even smaller than 0.13.

Summary

In summary, there is no evidence in favour of using second generation antipsychotics in treating anorexia nervosa. Patients, families, and clinicians are all left waiting for new and more effective treatments to be found.

The wait continues for evidence-based drug treatments to help patients with eating disorders.

Links

Primary paper

Dold M, Aigner M, Klabunde M, Treasure J, Kasper S. (2015) Second-Generation Antipsychotic Drugs in Anorexia Nervosa: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(2):110-6. [PubMed abstract]

Other references

Arcelus J, Mitchell AJ, Wales J, Nielsen S. (2011) Mortality rates in patients with anorexia nervosa and other eating disorders. A meta-analysis of 36 studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):724-31. [PubMed abstract]

Wu CS, Tsai YT, Tsai HJ. (2015) Antipsychotic drugs and the risk of ventricular arrhythmia and/or sudden cardiac death: a nationwide case-crossover study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(2).

The antipsychotic drugs don’t work for anorexia nervosa http://t.co/V2vXlqePtR #MentalHealth http://t.co/5NHcgahwcr

The antipsychotic drugs don’t work for #anorexia nervosa https://t.co/2AO7jbelVS

Antipsychotics are increasingly used for anorexia nervosa. But is there any evidence to support this practice? http://t.co/rIPzcJXROM

@Mental_Elf they’re used to dampen thoughts and slow down agitated state but not what is needed ! People with ED need specialist support !

@swmhltd @Mental_Elf Agreed

@Mental_Elf Interesting.

@Mental_Elf Very dangerous, damaging and not fit for purpose.

@Mental_Elf some for their weight gain S/E !?

@Mental_Elf it’s ridiculous to think b/c a med has weight gain S/E it will help AN; its b/c the meds increase appetite right?

@Mental_Elf ppl w/ AN only have AN b/c they’ve become very good @ignoring or just not caring about hunger;meds r never a sole fix for any MI

I’m not sure where this statement came from: “However, we do know that anorexia nervosa has a high mortality, which is not explained by increased rates of death by suicide” – that’s incorrect. There is abundant research showing one reason AN’s mortality rate is so high is suicide…. Something like half of all AN deaths are due to suicide. Also, using weight gain/BMI as the primary parameter in judging whether a medication works or not, for a person with anorexia, is a major flaw in these studies. For those who’ve experienced EDs, and are well-versed in the research into them — we all know weight, particularly BMI, is one of the most misleading factors by which to judge progress. That said – I am not at all in favor of antipsychotics being used for AN – centers have forced it on me and I have had horrible experiences with them (non-medical). Just wanted to point out a couple minor errors in some of your assessment of this meta-analysis. Thanks for the info.

Hello – sorry, you’re quite right re mortality – that sentence should say “not *entirely* explained by increased rates of death by suicide.

Re the use of BMI as an outcome measure, I agree with you that BMI alone does not equate to recovery from AN. I have focussed on it here, because it was the primary outcome measure in the metaanalysis, and in the majority of the papers on which the metaanalysis is based, and it was reported by all the trials (whereas they used different measures of other eating disorder pathology). I do also explain that there was also no difference between groups in measures of eating disorder pathology. I am sorry that you have had personal negative experiences of antipsychotics – always informative to also have a patient perspective.

I will reply to your other comment inline.

Thanks for the clarification Helen.

I have edited that sentence in your ‘Potential side effects of treatment’ section so it now reads:

“However, we do know that anorexia nervosa has a high mortality, which is not *entirely* explained by increased rates of death by suicide.”

Cheers,

André

A couple more thoughts to add :-). I’d like to ask to keep in mind that it’s not helpful to those suffering from AN to reinforce the stereotypes that 1) we all see a distorted version of our body in the mirror [never true for me], or 2) Every person battling severe AN is significantly underweight. In fact, many people with chronic, severe AN may pass as “normal” on the street. To reinforce the myth that you have to be grossly emaciated, or even 85% of ideal body weight, to have severe AN not only further “body-shames” AN individuals who aren’t grossly thin, but also may prevent treatment-seeking.

Thanks for your comments Jeanene.

I will ask Helen to respond directly to most of your points, but I just wanted to pick up on our choice of images for this blog. We have actually replaced one of the pictures that originally appeared on the blog (an image of a very thin woman) as after due consideration we felt it was not appropriate for an eating disorders post.

I would welcome any further comments about the remaining pictures. It is sometimes difficult to find good artwork for use on mental health blogs and eating disorders is an especially challenging subject to illustrate visually in a way that looks good but doesn’t cause offence.

Regards,

André

Thanks again for taking the time to read and comment.

I try to begin these Mental Elf pieces by setting a clinical scene as I hope it is engaging and gives people an idea of context. I didn’t make reference to seeing “a distorted version…in the mirror”. I described a patient as still being convinced she is “enormous” – I was trying to describe a self-perception of being too fat, which is one of the core ICD-10 criteria for AN.

I think I have to disagree on the semantics of your second point. I agree entirely that not all patients with Eating Disorders (bulimia nervosa, eating disorder otherwise specified etc) are underweight, let alone grossly emaciated. This group of normal weight but unwell people are I think less likely to seek treatment or be recognised as having an eating disorder, and this does need to be addressed. However, as the diagnostic manuals (DSM V and ICD 10) currently stand, to meet criteria for a diagnosis of full AN as opposed to another eating disorder, you do have to be underweight. ICD-10 states “a body weight of at least 15% below normal or expected weight for age and height”. If people have had AN but are now of normal body weight, they may still have an eating disorder, but it would have to be formally diagnosed as another eating disorder, for example Eating Disorder not otherwise specified (more than 50% of ED diagnoses are of EDNOS).

I second Andre re finding artwork for these pieces – always a challenge!

thanks again

@drbould Interesting comments on your blog from @JeaneneHarlick Care to respond? http://t.co/6Wk0L9SASH

@Mental_Elf @JeaneneHarlick sorry busy morning – thanks for your thoughts @JeaneneHarlick – reponse coming up soon!

#Antipsychotics don’t lead to weight gain or improve eating disorder symptoms in patients with #anorexia nervosa http://t.co/rIPzcJXROM

@Mental_Elf This is a really clear & useful summary. Thanks

Recent SR finds no evidence in favour of using second generation antipsychotics in treating anorexia nervosa http://t.co/rIPzcJXROM

.@Mental_Elf @ClinPsy what the???! I mean how…? WHO ON EARTH WOULD DO THIS?! why is that even a question??!

Don’t miss: The antipsychotic drugs don’t work for anorexia nervosa http://t.co/rIPzcJXROM #EBP

The #antipsychotic drugs don’t work for #anorexia nervosa http://t.co/4tNFCNv0s6 @Mental_Elf reviews the #evidence from a #metanalysis

The antipsychotic drugs don’t work for anorexia nervosa https://t.co/E5tdm76kDh via @sharethis

RT @BUELPsicologia: The antipsychotic drugs don’t work for anorexia nervosa – http://t.co/xbL2ia5bRT

My son could not stop bingeing on Olanzapine. He went from 45 kilos to 58 in a few weeks. Unfortunately we had to stop the medication as the urge to continually binge just took control and he was self-harming – it was just too dangerous to continue with it in a home setting. So, contrary to what you say in your post above, Olanzapine can result in considerable weight gain. Maybe my son has a particular sensitivity to it

Okay so I have anorexia and have been in hospital for over 8 months and been on quatiapine for ages and I CAN say I’ve gained a lot of weight and it’s HELL for me! I’m also on a feed via Ng tube so can’t say for definite but I’m ALARMED to find it causes weight gain so gonna ask if they can change me onto something different because I can’t take weight gain

Oh and I was on olanzapine and yes it does cause weight gain (although I was on it the whole time I was loosing weight…) So switched onto quatiapine…. Now gonna ask to be changed

“Meta-analysis” of only 200 patients?

Only two months duration?

What dose Seroquel, i highly doubt that 600 q hs would not stop someone from being delusional or not gaining weight (unless they were schizophrenia and needed Clozaril or dual antipsycotics.

What do I know, I’m just a foot soldier who’s worked primary care in jails, on a reservation, and in psych hospitals for 30 years; but the verdict is still out in my humble opine.

this study of the effects of antipsychotics in treating anorexia nervosa is not mature enough to measure the effects because psycological changes may take as long as a year as seen in treating depression. Also only looking at the resulting BMI and the cause effect relationships is bad practice since there are multiple factors to take into account as well as the possibility that some individuals partaking at the test may suffer from multiple problems that can cause weight loss.