Conflict of interest: I’m lucky enough to share an office with one of the co-authors of this paper, Hannah Dejong. I don’t think this has changed my ability to critically appraise the work, but I do admire Hannah’s integrity and intelligence, so maybe that makes me less critical.

I’ve said it before and no doubt I will have to say it again at some point: we’re not very good at treating anorexia nervosa. We don’t have many evidence-based treatments, and those we have are not great in terms of outcome and rates of drop out. Yet anorexia nervosa is a horrible illness to live with, exhausting for those suffering from it and those caring for them; we should be doing better than we are at treating it.

But there is hope. It has been recognised that things need to change, and that new, theory-based treatments should be developed, and here is one: “MANTRA – Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults” being rigorously tested against a manualised treatment as usual, “SSCM – Specialist Supportive Clinical Management”.

Treatments for anorexia nervosa need to improve.

Methods

So MANTRA (it’s all about having a catchy name, isn’t it?) was developed by Ulrike Schmidt and Janet Treasure, and it is a “cognitive-interpersonal treatment”, based on the theory that patients with anorexia nervosa (AN) have:

- “A thinking style characterised by inflexibility, excessive attention to detail, and fear of making mistakes;

- Impairments in the socio-emotional domain (e.g. difficulties in emotion recognition and theory of mind, avoidance of emotional experience and expression);

- Positive beliefs about how AN helps the person manage their life; and

- Unhelpful responses of close others, such as over involvement, accommodation to or enabling of symptoms, criticism, and hostility”.

Treatment draws on these ideas to make a formulation for each individual patient, and the therapeutic style is described as that of motivational interviewing. SSCM was designed for another trial, to standardise “Treatment as Usual” for anorexia, and includes assessing and reviewing target symptoms, psychoeducation, monitoring physical status, and nutritional advice.

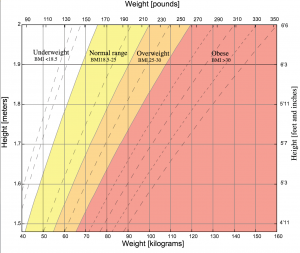

Therapists were trained in and delivered both treatments, and were supervised in both by different supervisors. Sessions were recorded to check for adherence. Patients with anorexia nervosa and those with EDNOS (Eating Disorder not otherwise specified) and a BMI <18.5 were recruited.

The primary outcome measure was BMI at 12 months and the study was powered to look for a difference between groups of 2.5kg weight gain. This, along with the rest of the trial design was pre-registered. The Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) was used to assess eating disorder psychopathology and various questionnaire measures of other psychopathology were used, as well as tasks of cognition and social cognition. Analysis was on an intention to treat basis, and was carried out by statisticians blind to treatment allocation.

This particular MANTRA intervention did not involve any drumming or chanting.

Results

One hundred and forty two participants from 4 centres were randomised to SSCM or MANTRA. On the primary outcome measure of BMI, there were no differences between groups at 6 or 12 month follow up. EDE score also did not differ between groups and neither did any other secondary outcome measure. Rates of use of other services were similar. Happily both groups did improve in terms of EDE and BMI, with at 12 months 81% of the SSCM group and 84% of the MANTRA group being partially or fully recovered (caveat: these percentages are of those not lost to follow-up).

75% of those in MANTRA completed their treatment, compared to 59% of SSCM (this is pretty good compared to other treatment; drop out has historically been a big problem in treatment of AN and treatment completion rates as low as 54% have been seen). This was reinforced by qualitative data suggesting patients prefer MANTRA.

The authors also did a subgroup analysis of those with a BMI <17.5, and they argue that this suggests MANTRA may be more beneficial in this group; although confidence intervals cross 1, so it isn’t possible to state this definitively (they were underpowered for this analysis).

Both treatments resulted in significant improvements in BMI and reductions in eating disorders symptomatology, distress levels, and clinical impairment over time.

Discussion

I think this is a well-designed trial and a thorough and honest analysis of the results. The authors reflect in the discussion on several possible limitations, including perhaps the most important: that MANTRA was designed in-house, and therapists and therefore patients may have been biased towards it. In a trial of medication, both patients and practitioners would be blinded to treatment; in psychological therapies you can’t do that, so the next best thing is to try to have providers as neutral as possible, ideally by testing away from the home of the therapy.

Another consideration in developing new psychological therapies is what to do with the control group. Do you do nothing (“treatment as usual” or “waiting list control”): this would give you a greater chance of finding a “positive” result for your new treatment. Or do you give an alternative treatment to control for the attention given to a patient having a psychological intervention; this enables you to be more certain that something specific about the treatment is working, and you aren’t just measuring placebo effect. If so, do you go for a “non-inferiority” design (this new treatment y will be at least as good as existing treatment x) or a superiority trial?

Here, the authors are appropriately cautious about what happens to their control group; this is a life-threatening illness, it wouldn’t be appropriate to put patients on a waiting list. But their control group doesn’t get normal TAU either; they get a strict manualised version of a kind of TAU which is probably very good. MANTRA had its work cut out trying to beat it; and it hasn’t succeeded.

For the patients in the trial this is a good deal; they definitely get something really good. And if it had come out ahead, that would have meant that there was something really special about MANTRA; definitely more than just a good therapeutic relationship and some sensible advice. But in fact it was a draw, and that is tricky for MANTRA: journals don’t rush to publish and health services don’t rush to implement treatments that are apparently no better than treatment as usual.

Maybe it is correct for health services not to implement a treatment no better than TAU (though I worry that most TAU isn’t as good as what the patients in this trial got), but perhaps a better option for the trial would have been to go for a non-inferiority trial with an active treatment like CBT-E; leaving open the possibility that if the two treatments were equal, future patients might have more choice about their treatment.

A future post will consider the results of the Strong Without Anorexia Nervosa trial, which compared CBT-E, SSCM and MANTRA in a neutral site, with therapists trained by the developers of each of the therapies, thus addressing both points raised above.

One final thought: it is often commented that eating disorders are not just about weight, yet the primary outcome measure in trials like this is often BMI. Of course we should measure it, and it should undoubtedly be an outcome measure, but should it be the primary outcome measure?

Should body mass index (BMI) be the primary outcome measure in eating disorders trials?

Links

Primary paper

Schmidt U, Magill N, Renwick B, Keyes A, Kenyon M, Dejong H, Lose A, Broadbent H, Loomes R, Yasin H, Watson C, Ghelani S, Bonin EM, Serpell L, Richards L, Johnson-Sabine E, Boughton N, Whitehead L, Beecham J, Treasure J, Landau S. (2015) The Maudsley Outpatient Study of Treatments for Anorexia Nervosa and Related Conditions (MOSAIC): Comparison of the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA) With Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM) in Outpatients With Broadly Defined Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000019

Photo credits

- Kevin Dooley CC BY 2.0

- Rio CC BY 2.0

- Paul De Los Reyes CC BY 2.0

- Dani Lurie CC BY 2.0

- “Body mass index chart” by Created by User:InvictaHOG using gnuplot and Adobe Illustrator 9/23/06, released into public domain – Created by User:InvictaHOG. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.

@Mental_Elf great question @drbould should BMI be the primary outcome measure for studies on anorexia ?

@ian_hamilton_ @Mental_Elf @drbould NO! Health is measured by many things, BMI is unsuitable & was never meant as a health tool.

A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/Q7tWGkNaYe #MentalHealth https://t.co/OYIK73xoye

RT iVivekMisra A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/49yq4Z5c43 #MentalHealth https://t.co/TrC2wyfQKX

A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/3MZRHT1P4E via @sharethis

Today @drbould on the #MOSAIC RCT on the Maudsley model of #Anorexia Nervosa treatment for adults https://t.co/djLCbrf73u #MANTRA

A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/rsMo3Ks6Vd @Mental_Elf looks at the evidence

A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/TkzUicZVnf

New #anorexia treatment leads to higher BMI, plus reductions in symptomatology, distress & clinical impairment https://t.co/djLCbrf73u

@Mental_Elf Very interesting. BMI should be the primary but not just the only consideration

Don’t miss: A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/djLCbrf73u

A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/PjJldsvPec via @sharethis

Study: #Maudsley treatment helps adults, too – much more than some conventional #eatingdisorder treatments. https://t.co/Pa8BGDTu0F

[…] 1A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa?- Mental Elf Blog post. […]

RT @ruairidhm: RT @Mental_Elf: A new MANTRA for treating anorexia nervosa? The MOSAIC study https://t.co/vhnI7nMIES

Hello, I have a daughter of 20 suffering from a severe anorexia for more than 6 years. Hospitals does not work, we are looking for useful treatment. I have just know about Mantra treatment, and also Crest and COPP. We do not know them at all. Could you help us in knowing further, who we have to contact, where, etc. We live in Barcelona, is possible to find trained specialists there? Thank you so much for any helpful idea, link or information.

I have been looking all through the handbook for MANTRA and ccan’t seem to find what their definition of recovery is.

What is the definition of revovery from anorexia when using MANTRA.

This article states that 84% of people in the study were either partially or fully recovered. When using MANTRA, What is partial recovery and what is recovery?

In order to get a percentage result a clear deinition of the term must be applied. If its not applied then how did they get the figure of 84%?

In order to arrive at this figure one assumes that those who were either partially or fully recovered fullfilled some kind of criteria. What was this criteria?

I have read the report and these vital defintions and criteria aren’t in it.

A clear definition of terms would be appreciated.

I have received a reply from Helen Bould and it appears that recovery is defined here as when one reaches a certain BMI.

In my extensive experience as both a sufferer(recovered) of anorexia and trained social worker and counsellor(specialising in eating disorders) that defining recovery in terms of weight gain and reaching an arbitrary BMI is not an accurate barometer of recovery.

Anorexia is primarily a mental illness that can effect physical health. Therefore it is imperative that the sufferers mental health is the barometer of recovery.

Weight gain is absolutely not an indicator(on its own)of recovery.

I have to say that in my experience, there is not such thing as partial recovery from anorexia.One cannot learn to live with it. The sufferer either controls the anorexia or it controls them in some way.

Anorexia is a terrible condition and in my view current treatments fail to understand the true nature of the disorder. Relapse rates are very high because of they way we treat anorexia.

There needs to be a total rethink on how we deal with it.

A clear start would be a definition of recovery that is focussed primarily on mental health rather than a weight gain based approach to defining recovery.

Until that happens then I fear that the sufferers of anorexia will continue to receive the wrong kind of treatmnent.

Hello Mark.. Would you possibly have any advice for me regarding treatment for anorexia. I have twin daughters who are both suffering from anorexia.. we are based in Liverpool. As you can appreciate they are extremely unwell both physically and mentally at the moment. Any advice would be greatly appreciated. Thank you.. Jamie