“There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.”

– Donald Rumsfeld

When Donald Rumsfeld pondered the nature of knowledge in front of the US Department of Defence in 2002, I doubt he had adult psychotherapy for depression at the forefront of his mind. Maybe he did. Who knows?

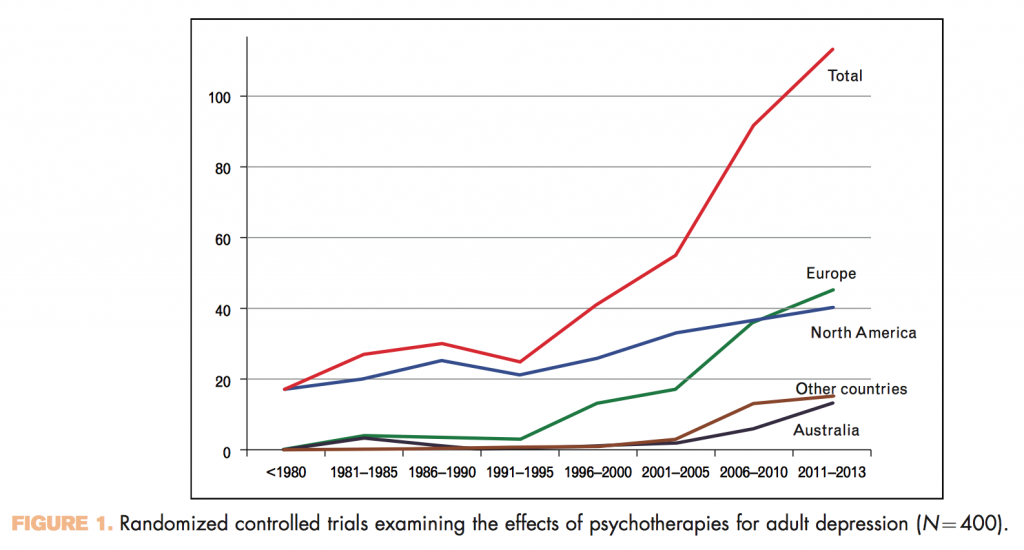

However Pim Cuijpers certainly did when, earlier this year, he published a piece in Current Opinions in Psychiatry. He considers what 400 randomised controlled trials of psychological treatments for adult depression, published over the past four decades, have told us about their clinical effectiveness. His view – we have learned much, but much is also still unknown.

This research is important because the disease burden of depression is significant. By one estimate, it is considered to be the illness ranked fourth highest worldwide in terms of disease burden, and is projected to become one of the top three, alongside HIV/AIDS and ischaemic heart disease, by 2030 (Mathers & Loncar, 2006). It is important too because depression is hard to treat. It is also prone to recurrence. However we have made significant advances, as the author explains.

This blog highlights an opinion piece by Pim Cuijpers, who is Professor of Clinical Psychology at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

The things we know we know

According to Cuijpers, research on psychotherapies for adult depression, conducted since the 1970s, has shown us a number of things:

1. Several types of psychotherapy are effective for depression

Now, psychologists love abbreviations. Particularly those involving three letters. We can’t help it. By the end of this section, you’ll know what I mean. Cuijpers highlights research into cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), behavioural activation therapy (BAT), problem-solving therapy (PST), supportive counselling and psychodynamic psychotherapy as all being found to be clinically effective in treating adult depression.

He also argues that, broadly speaking, all therapies are equally effective in the treatment of depression. He gives an interesting example of recent meta-analyses whose effect sizes between treatments were small (d=0.20), meaning that, via power calculation (with drop-out rate of 20%, alpha of 0.05 and statistical power of 0.80), a trial would need 491 patients in each arm to be adequately powered. As he points out, no such trial exists in the field of psychotherapy for depression.

Here we see a nudging in the direction of the trusty Dodo bird – a frequent woodland visitor in recent months (see Man, 2014; Kennedy-Williams, 2014; Shepherd, 2014). However, it is important to observe that there have been cases where one therapy is clearly superior to another (e.g. Kennedy-Williams, 2014), although not, in this case, for adult depression.

2. Research into psychotherapy for depression has grown

Considerably actually. Particularly, as you might expect, in Europe and North America but interestingly in non-Western countries too (see Fig. 1). Here, according to Cuijpers, there has been an increase in community-based projects. Where trained psychologists or psychotherapists are a scarce resource, lay health workers have been delivering simplified psychological treatments. This concept of scaling up psychotherapy services by simplifying treatments, highlights Cuijpers, is apparent in Europe too. He cites the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative in England as an example. Although I should highlight that the psychological workers delivering IAPT interventions are all trained and qualified to deliver them.

3. Psychotherapy doesn’t work for everyone

As Cuijpers observes here, modeling studies have shown that psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy combined can reduce the disease burden of depression by 33%. Over 40% of people do not respond, or only partially respond to treatment. Furthermore, relapse rates are high.

4. Much of the recent research focuses on ‘new’ psychotherapies

Cuijpers specifically cites two more recent psychotherapies; acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and cognitive bias modification (CBM). Although CBM is less a psychotherapy as such, rather a task-based approach to reducing unhelpful biases in one’s thinking. Again he highlights that, despite a proliferation in research, evidence maintains that these new treatments are no more effective than others already in existence. He argues that the quality of the evidence remains relatively poor.

The last 20 years has seen a dramatic increase in the quantity of published research about psychotherapy for depression, but study quality has remained low.

The things we know we don’t know

1. How much of the research has been affected by bias

We are largely able to assess where the research is biased by poor study design, and underpowered results, as this is often evident from reading the paper (though not always). We are less able, however, to detect the extent to which publication bias has affected our understanding. Essentially, we don’t know how many studies with null hypotheses have been conducted and not published. Cuijpers refers to a meta-analysis of CBT for adult depression (Cuijpers et al, 2013), which concludes that CBT is efficacious, but poor study design and potential publication bias probably affect the results.

2. Where next?

Although Cuijpers does argue quite strongly here. He suggests that to reduce the disease burden of depression, future research should veer away from ‘new’ psychological treatments. He argues:

Although many ‘new’ treatments promised to be more effective than existing therapies (for depression) in these four decades, no evidence has been found that this is indeed the case… The growing number of studies aimed at scaling up psychological services may … be helpful in further reducing the disease burden, such as training of lay-counsellors… telephone-based psychotherapies, and internet based therapies.

Cuijpers also cites treatments for chronic depression and relapse prevention as areas of important ongoing research.

Unpublished research remains a huge problem for systematic reviewers.

Key points

Cuijpers highlights five key points from the literature:

- In the past four decades, 400 randomised trials have examined the effects of psychotherapies for adult depression

- Although new therapies are continuously being developed, all therapies are equally effective in the treatment of depression

- There is also no evidence that recently developed new treatments, such as ACT and CBM, are more effective than existing treatments

- More progress is made in chronic depression and relapse wherein evidence is increasing that psychotherapies are indeed effective

- A growing number of studies are aimed at scaling up psychological services, such as the training of lay counsellors in low-income and middle-income countries, telephone-based psychotherapies, and internet-based therapies.

Increasingly, researchers are looking at interventions that allow us to scale up psychological services for entire populations.

Limitations

The first important limitation is that, being an opinion piece, rather than a systematic review of the literature, there is no mention of the search strategy used for the papers included. Nor have any study criteria been mentioned. So we are none-the-wiser regarding the studies that were selected, given specific mention, and so on.

Similarly, as the name suggests, here the author is providing just that; an informed opinion. That being said, the freedom of the opinion piece allows perhaps a wider net to be cast.

The paper also doesn’t distinguish much in terms of demographic details. Nor of the age of those involved in research, important due to the huge age-related bias of younger adults in psychotherapy literature.

Summary

Cuijpers argues that psychotherapies are essential tools in the treatment of adult depression. Evidence over the past four decades indicates that they are mostly effective. He also argues that often, new treatments do not lead to improved outcomes, and advises future research away from this.

I would argue, though, that clinical research is surely about developing and testing new ideas, in areas where we haven’t quite found the answer yet. Psychotherapy is certainly one of these areas. It can be incredibly helpful. But in the case of depression, for 40% of people it isn’t. The same is true of antidepressant medication. Therefore, the idea of abandoning research into developing ‘new’ treatments, such as CBM and ACT seems perhaps strange. However, his argument for scaling up the delivery of psychological interventions is a strong one, if we are to meet the often unmet needs of those experiencing psychological distress.

- So there are indeed things we know we know. For example, that psychotherapies for adult depression are important treatments. They are often clinically effective, but they don’t work for everyone.

- There is that of which we know we can’t be certain, such as the extent to which bias plays a role in these findings, and where future research will take us.

- As for the unknown unknowns? Who knows.

Cuijpers warns against following treatment fads and fashions, where the evidence doesn’t exist to support the intervention.

Links

Cuijpers, P. (2015). Psychotherapies for adult depression: recent developments. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 28(1), 24-29. [PubMed abstract]

Cuijpers, P., Smit, F., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., & Andersson, G. (2010). Efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy and other psychological treatments for adult depression: meta-analytic study of publication bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 196(3), 173-178.

Kennedy-Williams, P. (2014) RCT shows CBT is more effective than psychoanalytic psychotherapy for treating bulimia nervosa, but that’s only half the story. The Mental Elf, 16 May 2014.

Man, S. (2014). “Everyone’s a winner, all must have prizes!” but which psychotherapy for depression wins, if any? The Mental Elf, 30 January 2014.

Mathers, C. D., & Loncar, D. (2006). Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Medicine, 3(11), e442.

Shepherd A. (2014). Is the Dodo finally dead? The Mental Elf, 14 April 2014.

RT @Mental_Elf: Psychotherapies for adult depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t http://t.co/Z2khMnOnth

Psychotherapies for adult depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t: Patrick Kennedy-… http://t.co/XuFi8hbpLI

Known unknowns in the psychological treatment of depression via @Mental_Elf http://t.co/Y2H9aqclBA”

@Mental_Elf this was an excellent and helpful read – thank you for taking the time to convey this research, & your own thoughts, so clearly!

There’s never been an adequately powered clinical trial of psychotherapy for depression http://t.co/TkqBJGVCpW

@Mental_Elf Figuring out which therapies are likely to help which people (and why) would be a really helpful thing too.

Psychotherapies for adult depression http://t.co/SYHAZsqucq

Mirella Genziani liked this on Facebook.

Kirsten Corden liked this on Facebook.

Lucy Riddett liked this on Facebook.

Paula Gardiner liked this on Facebook.

Raluca Lucacel liked this on Facebook.

June Dunnett liked this on Facebook.

Today @paddy_kw channels @RumsfeldOffice and presents the known unknowns about psychotherapy for adult depression http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR

The Mental Elf liked this on Facebook.

Psychotherapies for adult #depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t http://t.co/4fv9MTKrIy #evidence

Rumsfeld, Cuijpers and psychotherapies for depression. http://t.co/xpylsWEe5q

In the past four decades, 400 randomised trials have examined the effects of psychotherapies for adult depression http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR

@Mental_Elf There is nothing worse, then going through hell of depression. Just keep fighting!

http://t.co/J9AJVPMnve

To be fair, articles in this journal ARE invited opinion articles (limited by space as well). So the lack of a systematic search is really not a limitation, it’s intrinsic to this kind of piece.

Inês Almeida liked this on Facebook.

Fiona Walker liked this on Facebook.

RT @Mental_Elf: Over 40% of people with depression do not fully respond to treatment and relapse rates are high http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR

#psychotherapy modes are equally effective in adult depression – need innovation and creativity http://t.co/8ysRI1N1tr @Mental_Elf

RT @Mental_Elf: Broadly speaking, all psychotherapies are equally effective in the treatment of adult depression http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR #do…

Interesting summary of psychotherapy for depression for @Mental_Elf: they work, but new treatments don’t work better http://t.co/R2XXI4PKq9

RT @cyberwhispers: #Psychotherapy for #depression: A number of therapies now known to be helpful. http://t.co/bSIbSD178p

Acceptance and commitment therapy & cognitive bias modification are currently popular with researchers http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR

Only when the benefit of medication ‘kicks In can a sufferer have the ability to challenge the mind set of the illness

RT @Mental_Elf: Publication bias remains a major problem when assessing the quality of psychotherapy research http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR #AllTr…

RT @Mental_Elf: Don’t miss – Psychotherapies for adult depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t http://t.co/Z2khM…

all therapies are equally effective in the treatment of depression http://t.co/ZEoWZFpTl3

Psychotherapies for adult depression http://t.co/Y87xJbyrlY via @nuzzel thanks @BPSOfficial

RT @suzypuss: Excellent review of opinion piece from a key researcher in the field Psychotherapies for adult depression. http://t.co/5WldN9…

Psychotherapies for adult depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t http://t.co/GTB8LLbO81 via @sharethis

Schizophrenia – Mom’s Journey liked this on Facebook.

Maria Wells liked this on Facebook.

“Psychotherapies for adult depression” http://t.co/NrA3N4sLxt

Psychotherapies for adult depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t know http://t.co/OXoEQcVUN1

Ilario Mammone liked this on Facebook.

Andy Conway liked this on Facebook.

Here’s the Bottom Line: help is available, and it works for most people -Psychotherapies for adult #depression http://t.co/QoxlzjTe6B

Fab summary of research heavyweight Cuijpers review article of psychotherapies for depression http://t.co/uoF5YAkddd

#Psychotherapies for adult #depression: the things we know we know, and those we know we don’t — http://t.co/Hxyc2XXhqS

Most popular blog this week? It’s @paddy_kw ‘doing a Rumsfeld’ on #psychotherapy for adult #depression http://t.co/Z2khMo5YRR

@Mental_Elf I’ve always wanted to do a Rumsfeld. I’m delighted..

Thoughtful blog on a paper on the effectiveness of psychotherapy for depression

http://t.co/7Hxw8T19ma

http://t.co/psvbmpmi6s

[…] http://www.thementalelf.net/mental-health-conditions/depression/psychotherapies-for-adult-depression… […]

No study of psychotherapy for depression exists that is adequately powered. It would require 491 patients in each arm http://t.co/rOXH7UzEoM

What we know and what we don’t know..

http://t.co/DkhQ1HVVgw