Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is common and disabling (Kessler et al., 2003). First-line treatments include psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) delivered as a course of weekly sessions, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) antidepressants, such as escitalopram, taken daily (NICE, 2009). The combination of psychological therapy and medication is thought to be more effective than either alone (ibid.).

Psilocybin assisted therapy is a package of psychological therapy, into which single dose treatments with psilocybin, given in a medically controlled and psychologically supportive environment, are embedded. The concept of psilocybin assisted therapy has precedent: prior to 1970 both psilocybin and d-lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) were used in the context of ongoing psychological therapy for a variety of conditions, such as alcoholism (Krebs & Johansen, 2012), depression (Rucker, Jelen, Flynn, Frowde, & Young, 2016), anxiety (Weston et al., 2020) and other forms of neuroses (Rucker, Iliff, & Nutt, 2018).

Recently, psilocybin assisted therapy for MDD has re-emerged as an area of interest. The team published a pilot trial (2016) in which 20 people with treatment resistant depression were given two psilocybin assisted therapy sessions, along with a package of psychological therapy, in an open label design (Carhart-Harris et al., 2017; Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). The findings showed a rapid and strong antidepressant effect, however the trial was open label in design (i.e. unblinded) and, therefore, uncontrolled for this possible bias.

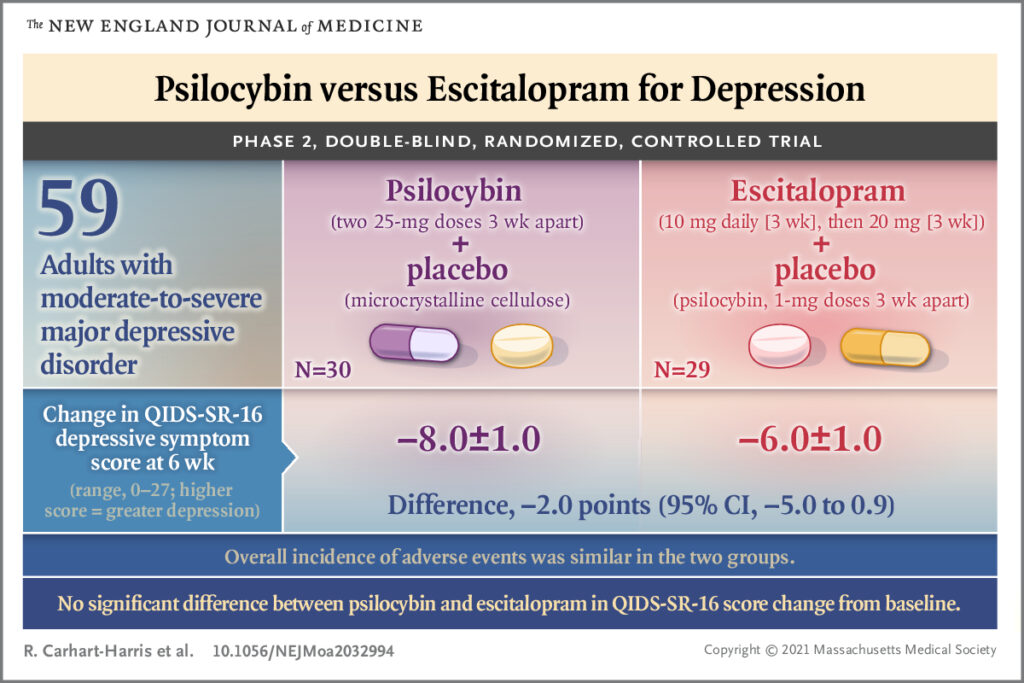

In this trial, the authors aimed to compare psilocybin assisted therapy with escitalopram assisted therapy in a randomised, blinded design (Carhart-Harris et al., 2021).

This randomised controlled trial compared psilocybin assisted therapy with escitalopram assisted therapy for major depressive disorder.

Methods

Fifty-nine participants between the ages of 18-80 with ‘longstanding, moderate-severe’ MDD not classified as treatment resistant were recruited. Recruitment was both formal and informal, however ‘most of the recruited participants referred themselves’. The main exclusion criteria were a personal or family history of psychosis, a history of serious suicide attempts, previous use of escitalopram or contraindications to taking SSRIs or having an MRI scan. The researchers sought confirmation of diagnosis and eligibility from participant’s primary care physicians in all cases. Diagnosis of depression was made according to DSM-5 criteria, though the authors state the MINI was used (circa 2000, preceding DSM-5). Participants were required to have a score of 17 or more on the clinician rated Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

After screening for eligibility, participants entered a preparatory phase in which they were withdrawn from existing psychiatric medication and established rapport with two mental health professionals who then accompanied the participants through the trial. The baseline visit was at the end of the preparatory phase.

Randomisation by blocks of 8 was performed to allocate participants to two comparator conditions. Participants were allocated either to two dosing sessions consisting of 25mg of psilocybin or to two dosing sessions consisting of 1mg psilocybin.

- For those participants allocated to 25mg psilocybin, they received one placebo capsule daily after dosing session 1 and two placebo capsules daily after dosing session 2.

- For those participants allocated to 1mg psilocybin, they received one 10mg escitalopram capsule daily after dosing session 1 and two 10mg escitalopram capsules after dosing session 2.

- All participants received psychological support.

Six face-to-face study visits were undertaken in total. One was at screening, one was at baseline, two were dosing sessions, and two were post dosing visits. In-between visits, all participants received psychological therapy by video conferencing.

The primary outcome was change from baseline in score on the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR) at 6 weeks. There were sixteen secondary outcomes.

The primary endpoint was at 6 weeks. After this the blind for each participant was broken to inform a clinical decision about ongoing treatment after the participant’s care was handed back to referrers.

Results

Approximately 1,000 people were assessed for eligibility. 891 were excluded for not meeting eligibility criteria and 50 declined to participate. 59 were randomised.

Participants were mostly male (66%), white (88%), highly educated (73% had a university degree or higher) and not taking antidepressants (61%) prior to their enrolment. Seventy-three per cent had not used psilocybin prior to the trial.

For the primary outcome (QIDS-SR 16), there was no statistically significant difference between the comparator groups at six weeks (2.0, 95% CI -5.0 to 0.9, p=0.17) when baseline QIDS-SR 16 scores were taken into account.

For the 16 secondary outcomes, the majority nominally favoured the psilocybin group versus the escitalopram group. Within the secondary outcomes, a QIDS-SR-16 response at 6 weeks occurred in 70% of the psilocybin group versus 48% in the escitalopram group (95% CI for difference, -3 to 48) and a QIDS-SR-16 remission rate at 6 weeks occurred in 57% of the psilocybin group versus 28% in the escitalopram group (95% CI for difference, 2.3 to 53.8). The difference in the change in the clinician rated Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS), a widely accepted measure of depressive symptoms, at 6 weeks between conditions was -7.2 points (95% CI -12.1 to -2.4), favouring psilocybin. The MADRS scale, as well as other clinician rated scales, were collected by individuals who were also part of the core trial team. The authors commented that they did not pre-register an intention to correct these outcomes for multiple comparisons, thus the 95% confidence intervals do not reflect this. Thus, the authors state no clinical conclusions should be drawn.

There was no statistically significant difference in the primary outcome measure between the psilocybin and escitalopram groups at six weeks. Secondary outcomes nominally favoured psilocybin.

Conclusions

For the pre-registered primary outcome measure in this trial there was no statistically significant difference in participant reported depression symptoms between the group that received 25mg psilocybin/placebo and the group that received 1mg psilocybin/escitalopram. For secondary outcomes, the data nominally favoured the psilocybin/placebo group, however it would not be appropriate to draw clinical conclusions from this.

This trial did not show a statistically significant difference between psilocybin assisted therapy and escitalopram assisted therapy for major depressive disorder at 6 weeks.

Strengths and limitations

Whilst of modest size overall, this trial recruited more participants than previous studies in this particular area and it appears to have been well conducted. The research team and institution have a good reputation for conducting research in this area. The findings represent a novel addition to the scientific literature that addresses a significant gap in knowledge.

This trial lacked a placebo control condition, which makes it difficult to differentiate between the two drug treatments and the psychological therapy that went along with these. In any event, it is not clear whether the trial was powered to demonstrate non-inferiority (i.e. robust enough to show that psychological therapy given alone was not significantly worse than the comparators).

It is likely that participants were given extensive psychological support. The results of this trial may reflect more the therapeutic efficacy of attentive psychological therapy than to psilocybin or escitalopram.

The sample in this trial was predominantly white, male and highly educated, whereas depression is known to be over-represented in women and those with markers of socioeconomic deprivation (Kessler et al., 2003). This may limit generalisability of these findings.

The follow up for this trial was six weeks, which may not be long enough to effectively evaluate the escitalopram condition, particularly given that the escitalopram dose was increased at 3 weeks.

It is unclear to what extent unblinding played a role in this study. The authors did not assess unblinding by asking the participants which condition they thought they were allocated to.

Positive and negative expectancy effects are likely to have affected the results in this trial and are liable to bias results in favour of psilocybin. Moreover, comparing escitalopram to psilocybin may not be considered a ‘like-for-like’ comparison.

Researchers were allowed to exclude people they did not feel they had formed a rapport with. Whilst this may be necessary in a trial that includes therapy, it is likely also to introduce a form of selection bias that is not accountable for in the analysis.

The results of this trial may reflect more the therapeutic efficacy of attentive psychological therapy than to psilocybin or escitalopram.

Implications for practice

This is an early phase clinical trial, so implications for clinical practice are limited. Given that existing treatments for MDD, particularly SSRIs delivered in primary care, are inexpensive and relatively safe and effective, it is not clear whether psilocybin assisted therapy would be accepted as a first-line treatment for MDD by healthcare providers. Last but not least, this trial adds to the evidence that psilocybin assisted therapy may be an alternative treatment for MDD, but does not confirm this.

Psilocybin assisted therapy may be a viable treatment for depression, but much larger studies are needed to confirm this and significant barriers remain to its implementation.

Statement of interests

JR leads the Psychedelic Trials Group with Professor Allan Young at King’s College London. He had no involvement in this study.

Links

Primary paper

Carhart-Harris, R., Giribaldi, B., Watts, R., Baker-Jones, M., Murphy-Beiner, A., & Murphy, R. et al. (2021). Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression. New England Journal Of Medicine, 384(15), 1402-1411. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2032994

Other references

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Day, C. M. J., Rucker, J., Bloomfield, M., Watts, R., . . . Taylor, D. (2017). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 399-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-017-4771-x

Carhart-Harris, R. L., Bolstridge, M., Rucker, J., Day, C. M., Erritzoe, D., Kaelen, M., . . . Nutt, D. J. (2016). Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: an open-label feasibility study. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(7), 619-627. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30065-7

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Koretz, D., Merikangas, K. R., . . . Wang, P. S. (2003). The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 289(23), 3095–3105.

Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P. O. (2012). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol, 26(7), 994-1002. doi:10.1177/0269881112439253

NICE. (2009). Depression in adults: recognition and management: Clinical guideline [CG90]. Last accessed: 21 June 2021.

Rucker, J. J., Jelen, L. A., Flynn, S., Frowde, K. D., & Young, A. H. (2016). Psychedelics in the treatment of unipolar mood disorders: a systematic review. J Psychopharmacol, 30(12), 1220-1229. doi:10.1177/0269881116679368

Rucker, J. J. H., Iliff, J., & Nutt, D. J. (2018). Psychiatry & the psychedelic drugs. Past, present & future. Neuropharmacology, 142, 200-218. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.12.040

Weston, N. M., Gibbs, D., Bird, C. I. V., Daniel, A., Jelen, L. A., Knight, G., . . . Rucker, J. J. (2020). Historic psychedelic drug trials and the treatment of anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety, 37(12), 1261-1279. doi:10.1002/da.23065

Photo credits

- Photo by Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition on Unsplash

- Photo by John Simitopoulos on Unsplash

Fascinating work, and it will be interesting to see how this area develops, and longer term follow-up studies reveal.

Although polite and gentle, this review of the trial reaches some unavoidable conclusions: (1) psilocybin is not any better than an SSRI for depression, (2) short follow up time was in favor of finding an effect for psilocybin,(3) there is no reason to prefer psilocybin over an SSRI, particularly given the elaborate preparations and dubious coaching of a response required by psilocybin. (4) the severity and nature of the depression of patients recruited to this trial discourages combining the data with data from other trials that claimed to recruit treatment resistant depression.

These points occur in some sophisticated, but accessible comments on this study as a drug trial.

I would not be bothered if these authors objected to my tone or content. But in a recent article, I argued that the preparation, therapy during the administration of the drug, and “integration sessions” afterward, the psychological treatment was not evidence-based and positively woo woo, and made no sense to patients assigned to the SSRI who quickly became unblinded.

Basically, the lack of differences between psilocybin and SSRI was obtained despite getting psilocybin being delivered with a placebo of massive intensity that did not work for the SSRI

https://medium.com/beingwell/clinical-trials-of-psychedelics-got-wrong-the-basics-of-psychotherapy-development-758f610b271e