Adolescence is a period rife with uncertainty for the young person.

As we seek to discover who we are (Yurgelun-Todd, 2007), and how we respond to the changing connections we make in our relationships, the reorganisation of neurobiological networks in the brain serve to shape the behaviours of the adults we become in the world.

The neural pathways underlying this ‘sense of self’ and the regulation of our emotional responses to things targeting that self-reference (Herbert et al, 2010), are increasingly understood as key to the emergence of subclinical emotional symptoms that precede developing affective disorders such as depression (Bradley et al, 2016).

Dynamic rather than static Functional Network Connectivity (dFNC), i.e. viewing connectivity in the context of temporal changes in the brain especially in this critical period of reorganisation, has recently emerged as a reproducible and promising target for study (Abrol et al, 2017) with the use of functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI).

This new primary study by Malhi et al (2019), aims to address the paucity of research using dFNC to study the neural basis for the emergence of subclinical emotional symptoms, hypothesising that in their cohort of adolescent females there will be a difference in which key connecting networks are identified and how they connect, between individuals with (ES+) and without (ES-) emotional symptoms, with a potential implication on future clinically significant symptoms.

The study of spatiotemporal changes in the functional connectivity of neural pathways in adolescence, may be key to understanding the emergence of symptoms of affective disorders.

Methods

This follow up study recruited a total of 88 adolescent girls (mean age 15 years).

At first meeting (T1), they underwent neuroimaging, and answered a series of relevant questionnaires such as the:

- Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)

- State (SA) and Trait Anxiety (TA): State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

- Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS)

At second meeting (T2), no further neuroimaging was conducted, only the answering of the same questionnaires as completed at T1.

Presence or absence of emotional symptoms were determined by:

- Responses from questionnaires attaining thresholds set by the Child and Adolescent Psych Profiler (CAPP), which a previous study demonstrated was a useful tool to identify adolescents ‘vulnerable’ to affective disorders (Das et al, 2013)

- Past medical history of intervention or treatment for an existing affective disorder

Neuroimaging included structural and functional MRI which gathered 155 whole-brain volumes of data. This was cleaned in three stages:

- Pre-processing: removal of artefacts, reorientation, normalisation and smoothing in stereotactic space, correction for various small sources of error and despiking to mitigate outliers

- Group Independent Component Analysis (ICA): data was reduced and concatenated, in a manner that sample-specific maps/time courses could be identified via spatiotemporal regression back-construction

- Post-ICA-processing: random effect analysis was used to identify peak activation clusters with low overlap with brain ‘edge regions’, with the criteria that relevant neural networks in self-referential processing and emotional regulation such as Default Mode Network (DMN), lateral/medial prefrontal cortices (l/MPFC), inferior/superior parietal lobule or temporoparietal junction be represented. Data was detrended, orthogonalized and again despiked.

To study dFNC:

- GIFT and Matlab was used, to concatenate covariant metrices at the group-level and explain changes as a function of time

- Two-sample t-tests were used to identify difference in dFNC between ES+ or ES- groups at both T1 and T2

- Individuals who remained ES+ or ES- at both T1 and T2 were also studied

- Regression analyses were performed with symptom change between T1 and T2 as dependent, and symptom at T1 and Δ(dFNC) were independent variables, to identify whether dFNC differences between all ES+ or ES- participants, contribute to the emergence of future clinical symptoms.

Results

Of the recruited sample, 71 participants completed the study (ES+ n=27, ES- n=44).

Salient results indicated:

- ES+ individuals experienced greater psychopathology, and lower emotional regulation, than ES- individuals in the study (see table 1 in the paper)

- 7 DMN, 7 frontal and 14 attentional network components of significance were identified

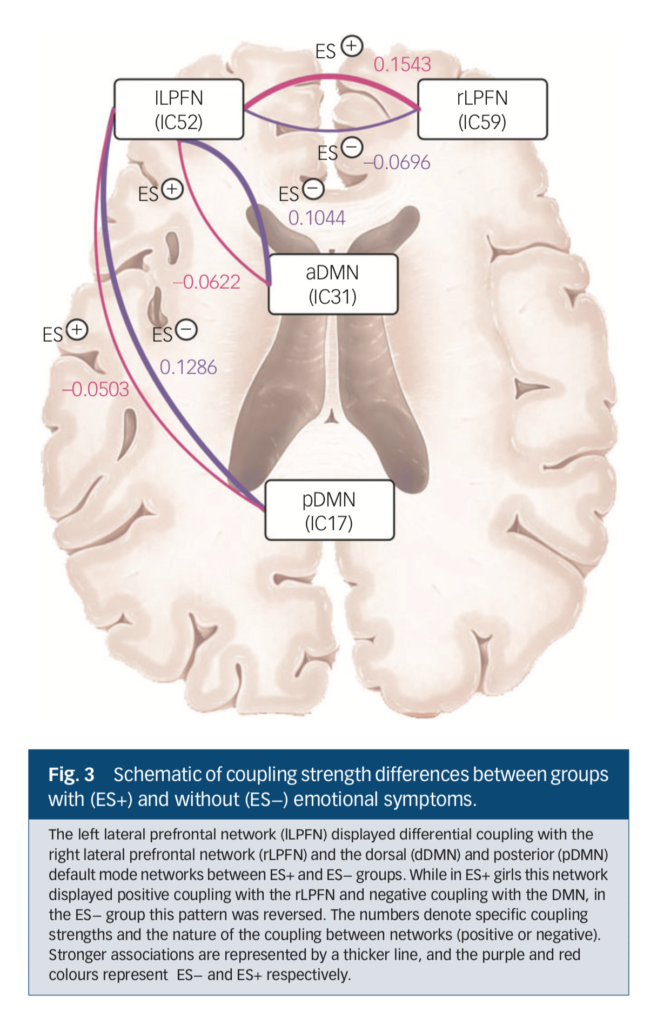

- dFNC only showed significant difference between ES+ and ES- groups in state 2, and identified four networks between which coupling differed in the groups:

- midline posterior and frontal cortices of the DMN (pDMN and aDMN)

- left and right lateral prefrontal networks (lLPFN and rPFN)

- There were 3 significant connectivity differences between groups, between lLPFN, and the rLPFN, aDMN and pDMN. This was true for all ES+ and ES- participants, including those who remained ES+ and ES- at both T1 and T2

- Clinically relevant, lLPFN-rLPFN functional connectivity contributed to the changes in CDI and SA between the time points, explaining greater variance with the coupling than through T1 assessment alone (CDI: 21.9% vs. 13.8% at T1; SA: 24.8% vs. 21% at T1).

There were three significant coupling differences between groups: ES+ positively coupled lLPFN-rLPFN, and negatively coupled pDMN and aDMNm and ES- showed the opposite relationships.

Conclusions

Using dFNC, this study identifies increased interaction of the lateral prefrontal networks (lLPFN-rLPFN) and decreased interaction of the Default Mode Networks (pDMN-aDMN), as neural bases of the emergence of emotional symptoms in adolescent females, particularly with clinical promise in symptoms linked to depression and state anxiety.

It is postulated that the rise of emotional symptoms is attributable to a goal-seeking and failure-based approach to the emergence of depression:

- Approach-and-avoidance behaviours are important to maintaining homeostasis and health, and these are regulated by the LPFCs (Spielberg et al, 2013)

- The DMN is implicated in goal-setting (Strauman et al, 2013), be this for idealised goals with a positive reward, or goals of a responsibility which seek to avoid a negative consequence, relative to self-referential processing

- Hence, due to the differences in LPFN and DMN connectivity between ES+ and ES- individuals, it may be that goal-setting and strategies for approaching or avoiding them is impaired, which may result in failure of outcomes

- This cognitive impairment may contribute to an inability to maintain positive affects while negative affective symptoms are more deeply ingrained over time, which could lead to the development of clinical affective disorders such as depression in adulthood, as preceded by the depressive and state anxiety symptoms seen in this cohort.

Approach-and-avoidance behaviours towards ideal and obligatory goal-setting may be compromised due to differential network connectivity in individuals with emotional symptoms in adolescence, potentiating clinical affective disorders in adulthood.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides a robust and detailed description of the methodology used to arrive at their results, and conclusions. Especially with the novelty of using dFNC to study the emergence and development of emotional symptoms in this cohort, this inspires confidence and provides a clear roadmap for other groups to investigate the reproducibility of these data and conclusions.

A roadmap for future research would need to start by addressing the limitations acknowledged by the authors:

- Gender bias due to only female participants limiting study generalisation to male adolescents (or those of a varying gender identity)

- Limited number of networks studied when other networks of equal importance may be implicated in the emergence of emotional symptoms in adolescence

- Liberal call of ‘presence of emotional symptoms’ using the CAPP as any non-specific emotional symptom could be the precursor to one of many clinical affective disorders (as per the DSM-IV-TR) in adulthood

- Lack of a current longitudinal study investigating emotional symptoms from adolescence to adulthood leaves uncertainty as to whether other confounding factors investigated in this paper may affect the development of full clinical disorder in adulthood

Future studies should extend beyond the current age of participants, involve male adolescents, and study other networks to identify whether non-specific emotional symptoms are linked to any other specific disorders of adulthood.

Implications for practice

Direct implications for practice from this singular study are limited until the reproducibility of its data can be demonstrated and its limitations addressed, particularly through extending a longitudinal study of the same context into the connectivity of DMN and LPFN with other networks.

This may be of clinical interest, as patterns from this study in the potential development of affective disorders due to differential self-referential processing and emotional dysregulation, are reflected in trends of research in other branches of neuropsychiatry such as pharmacology, e.g. in the utility of psychedelics in the treatment of affective disorders by disrupting functional connectivity.

It is postulated that the connectivity of the DMN is that which allows for the perception of a waking ‘sense of self’, or metacognition’ (Carhart-Harris et al, 2014). A greater increase in DMN connectivity coherence (Greicius et al, 2007), especially in areas of the aDMN (Zhu et al, 2012) has been demonstrated in depressed patients than unhealthy controls. The introduction of psychedelics such as psilocybin to cause ‘ego-dissolution’ (Carhart-Harris et al, 2014), i.e. reducing the resting state functional connectivity (RSFC) between these areas, may represent one of many fascinating methods to study for the disruption of neural networks implicated in depression by this study and other contemporary or subsequent investigations.

Patterns from this study in the development of affective disorders due to differential self-referential processing and emotional dysregulation, are reflected in trends of novel research in neuropsychopharmacology

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Malhi G, Das P, Outhred T, Bryant R, Calhoun V. (2019) Resting-state neural network disturbances that underpin the emergence of emotional symptoms in adolescent girls: resting-state fMRI study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2019;215(3):545-551. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2019.10 [Pubmed abstract]

Other references

Yurgelun-Todd D. (2007) Emotional and cognitive changes during adolescence. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2007;17(2):251-257. [Pubmed abstract]

Herbert C, Pauli P, Herbert B. (2010) Self-reference modulates the processing of emotional stimuli in the absence of explicit self-referential appraisal instructions. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;6(5):653-661.

Bradley K, Colcombe S, Henderson S, Alonso C, Milham M, Gabbay V. (2016) Neural correlates of self-perceptions in adolescents with major depressive disorder. (PDF) Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2016;19:87-97.

Abrol A, Damaraju E, Miller R, Stephen J, Claus E, Mayer A et al. (2017) Replicability of time-varying connectivity patterns in large resting state fMRI samples. NeuroImage. 2017;163:160-176.

Das P, Coulston C, Bargh D, Tanious M, Luan Phan K, Calhoun V et al. (2013) Neural Antecedents of Emotional Disorders: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study of Subsyndromal Emotional Symptoms in Adolescent Girls. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):265-272.

Spielberg J, Heller W, Miller G. (2013) Hierarchical Brain Networks Active in Approach and Avoidance Goal Pursuit. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2013;7.

Strauman T, Detloff A, Sestokas R, Smith D, Goetz E, Rivera C et al. (2013) What shall I be, what must I be: neural correlates of personal goal activation. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2013;6.

Carhart-Harris R, Leech R, Hellyer P, Shanahan M, Feilding A, Tagliazucchi E et al. (2014) The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2014;8.

Greicius M, Flores B, Menon V, Glover G, Solvason H, Kenna H et al. (2007) Resting-State Functional Connectivity in Major Depression: Abnormally Increased Contributions from Subgenual Cingulate Cortex and Thalamus. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):429-437.

Zhu X, Wang X, Xiao J, Liao J, Zhong M, Wang W et al. (2012) Evidence of a Dissociation Pattern in Resting-State Default Mode Network Connectivity in First-Episode, Treatment-Naive Major Depression Patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2012;71(7):611-617. [Pubmed abstract]

Photo credits

- Photo by Yoab Anderson on Unsplash

- Photo by Sharon McCutcheon on Unsplash

- Photo by Kaylah Otto on Unsplash

- shroom360 [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons