Two thirds of people with dementia in the UK live at home (Prince et al., 2014). They receive home support to help them manage living independently for as long as possible, which is provided to a large extent by their family members (Schneider et al., 2003). So, to live independently, providing support in managing everyday activities is a vital element, as people with dementia experience problems with managing their medication and preparing a meal early on (Giebel et al., 2014).

But supporting people with everyday tasks isn’t the only symptom that requires to be addressed and managed. People with dementia also display behavioural problems, such as changes in sleeping patterns or agitation (de Vugt et al., 2006). Problems with cognition are also well-known (Liu-Seiffert et al., 2015), which can cause the person with dementia to repeatedly ask the same question or forget important appointments. Similarly, communication is often impacted too, which can make it difficult for people with dementia to explain their needs (Trahan et al., 2014).

All these symptoms can cause family carers to be more and more distressed (Sutcliffe et al., 2016). But even for those people without a family carer, there may come a point where a long-term care (LTC) facility is the most appropriate place (Tucker et al., 2016). Indeed, long-term care placement is one of the biggest cost factors in dementia care (Vossius et al., 2014), so it is important to understand how we can support people with dementia live at home for longer. But how exactly do different symptoms, and other factors, predict admission into a LTC facility?

In this blog, I am looking at a recent review and meta-analysis by Cepoiu-Martin and colleagues (2016) that addresses precisely this issue.

Placement in long-term care facilities is one of the biggest costs of dementia care.

Methods

The authors used various medical and sociological electronic databases for their literature searches. Only studies published in English and between January 1990 and January 2015 were included. The search terms included dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and Lewy Body disease, as well as nursing home, LTC, and assisted living, amongst others. People with dementia had to live in the community at the beginning of the study and had to have been followed up regarding their living situation.

Two reviewers then independently reviewed 4,814 titles and abstracts, and subsequently read through 358 full texts. In total, 59 studies were included in the review, of which 37 were included in the meta-analysis. The reviewers rated the methodological quality of each study with the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for cohort studies.

To assess the predictors of long-term care placement and the time until placement, the reviewers used survival analysis method with the data from the studies and contacted authors for further data if not published. Where the authors couldn’t explore the data, a narrative analysis was conducted.

The researchers pooled data from publications over a 15 year period to try to identify factors that predict admission to long-term care facilities.

Results

Most included studies had one common quality issue, namely the assessment of long-term care placement. This was mostly provided through self-reports, and not independently assessed by the researchers of the studies.

Looking at the characteristics of people with dementia, there were several significant predictors of long-term care placement. Increased age, everyday activity impairment, and behavioural and psychological problems, being White Caucasian, and being in the severe stages of dementia were significant predictors of long-term care placement.

On the other hand, being married and living with a family carer offered a significantly lower risk of entering a care home. The type of dementia, so Alzheimer’s disease or Lewy Body dementia for example, did not affect long-term care placement.

For the carers of someone with dementia, being a female carer resulted in a lower risk of admission. Increased carer burden increased the risk of being admitted into a LTC facility. Depressive symptoms were not significantly related.

Living with a family carer was associated with lower risk of admission to a long-term care facility.

Limitations

There are few limitations to this paper. The authors reviewed a large selection of databases and included papers spanning 25 years of research. One limitation might be that authors only included papers in English, whilst other research was neglected. Although the authors have included a large number of studies, papers from non-English speaking countries published in German or Swedish for example might have added some further insights.

Furthermore, as the authors have also discussed, a potential flaw of meta-analyses in general is the use of aggregated patient data and not individual data. So, some more nuanced variations or predictors might not be picked up.

Summary

This paper offers a good summary of the predictors of long-term care placement in dementia. Although the topic has been explored in depth already, and systematic reviews have been published on this topic in the past, this paper provides not only an overview, but furthermore re-analyses the existing data, merged together.

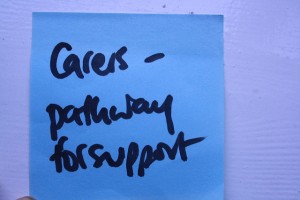

There are indeed a lot of predictors that increase the risk of long-term care placement in dementia. Whilst some predictors cannot be changed, such as race, age, or being married, or indeed the gender of a carer, other can be addressed. One predictor that should be addressed in relation to every person receiving a diagnosis is carer burden. Too often, carers are being left out of the health and social care remit and are not offered any support. However, carers are shown to benefit from peer support groups and can receive targeted training in order to manage better with the dementia symptoms (Mittelmann et al., 2004). In view of no cure, yet, being psychologically better able to cope can prove a vital, and easily achievable step, in the management of dementia.

Other areas can focus on maintaining the ability to live independently and to train people with dementia techniques to perform everyday activities again or to continue to do so (i.e. Giebel & Challis, 2015). But let’s not forget the impact that the environment can have on someone with dementia – it can both hinder performing everyday tasks, but can also cause behavioural problems (Horvath et al., 2013).

So, maybe some simple changes (to the environment) can also help reduce some of those risk factors, and help people to stay in their own home for as long as possible.

Carers can benefit from peer support groups including targeted training in order to manage dementia symptoms better.

Links

Primary paper

Cepoiu-Martin, M., Tam-Tham, H., Patten, S., Maxwell, C.J., & Hogan, D.B. (2016). Predictors of long-term care placement in persons with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, doi: 10.1002/gps.4449 [Abstract]

Other references

deVugt, M.E., Riedijk, S.R., Aalten, P., Tibben, A., van Swieten, J.C., & Verhey, F.R.J. (2006). Impact of Behavioural Problems on Spousal Caregivers: A Comparison between Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22(1), 35-41.

Giebel, C. and Challis, D. (2015). Translating cognitive and everyday activity deficits into cognitive interventions in mild dementia and mild cognitive impairment. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(1), 21-31.

Giebel, C.M., Challis, D. and Montaldi, D. (2014a). A revised Interview for Deteriorations in Daily Activities in Dementia (R-IDDD) reveals the relationship between social activities and well-being. Dementia, doi: 10.1177/1471301214553614

Horvath, K.J., Trudeau, S.A., Rudolph, J.L., Trudeau, P.A., Duffy, M.E. and Berlowitz, D. (2013). Clinical trial of a home safety toolkit for Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, doi: 10.1155/2013/913606.

Liu-Seiffert H, Siemers E, Sundell K, et al. 2015. Cognitive and Functional decline and Their Relationship in Patients with Mild Alzheimer’s Dementia. J Alz Dis 43:949-955.

Mittelman, M.S., Roth, D.L., Coon, D.W. and Haley, W.E. (2004a). Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry,161(5), 850-6.

Prince, M. et al. (2014). Dementia UK: Update. Alzheimer’s Society: London.

Schneider, J. et al. (2003). Formal and informal care for people with dementia: variations in costs over time. Ageing and Society, 23(03), 303-326.

Sutcliffe, C., Giebel, C. M., Jolley, D., & Challis, D. (2016). Experience of burden in carers of people with dementia at the margins of long-term care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(2), 101-108.

Trahan, M.A., Donaldson, J.M., McNabney, M.K., & Kahng, S.W. (2014). Training and maintenance of a picture-based communication response in older adults with dementia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 47(2), 404-409.

Tucker, S., Brand, C., Sutcliffe, C., Challis, D., Saks, K., Verbeek, H., … RightTimePlaceCare Consortium (2016). What Makes Institutional Long-Term Care the Most Appropriate Setting for People With Dementia?: Exploring the Influence of Client Characteristics, Decision-Maker Attributes, and Country in 8 European Nations.Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 17(5), 465.e9-465.e15

Vossius, C., Rongve, A., Testad, I., Wimo, A. and Aarsland, D. (2014). The Use and Costs of Formal Care in Newly Diagnosed Dementia: A Three-Year Prospective Follow-Up Study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22(4), 381-388.

Today @ClarissaGiebel on predictors of long-term care placement in people with #dementia https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq

Care home placement in #dementia – my new @SocialCareElf #Blog https://t.co/qnFZB21l9L @beatdementia @BetterResearch @3SpiritUKNZ #demphd

What predicts care home placement in #dementia? My new @SocialCareElf Blog https://t.co/qnFZB21l9L @MICRA_Ageing @EneidaMioshi @UoMPolicy

Blog-Predictors of care home placement in dementia https://t.co/qnFZB21l9L via @SocialCareElf @AlzheimerEurope @Angela_Aldridge @DiverseAlz

New #Blog by #pssru @ClarissaGiebel on predictors of care home placement in #dementia @SocialCareElf https://t.co/EHdDuVm2yB

Blog on predictors of care home placement in #dementia via @SocialCareElf https://t.co/EHdDuVm2yB @SCIE_sco @PSSRU_LSE @JamBrown

Placement in long-term care facilities is one of the biggest costs of dementia care https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq

‘Long-term care placement for people with dementia’ – https://t.co/71MTf9yUnC @ClarissaGiebel for @SocialCareElf

Why do people with #dementia enter a #carehome? #blog https://t.co/qnFZB21l9L @HIRL_MMHSCT @UEA_Health @lbsorg @tide_carers @Anthony_Hodgson

Systematic review identifies factors that predict admission to long-term care facilities in people with #dementia https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq

Carers can benefit from peer support groups including targeted training in order to manage dementia symptoms better https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq

Long-term care placement for people with dementia https://t.co/mXOttr4L0e via @sharethis @SocialCareElf

Living with family #carer assoc w lower risk of admission to long-term care facility, says new review https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq #dementia

Don’t miss: Long-term care placement for people with dementia https://t.co/2UqSN4tDOq #EBP

Long-term care placement for people with dementia https://t.co/Db0ekeIIW7 via @sharethis

New @SocialCareElf blog on why people with #dementia enter a #carehome https://t.co/EHdDuVm2yB @InstforDementia @Dementia_UoB @ripaljeet

Living with a family carer &having a female #carer linked to lower risk of entering a carehome #dementia https://t.co/qnFZB21l9L @UKCareHelp

Predictors of long-term care placement in #dementia – @SocialCareElf https://t.co/rN1uOqO0Gg https://t.co/WQlBk8cFpB

Findings seem rather obvious. People are much more likely to need care homes if they are older, have greater need for support, or have behavioural issues. And less likely to be in a care home if they have a supportive partner or family. Eureka!

Why aren’t we researching what services would support people to stay out of care homes or improve person-centred care within care homes?