Dementia affects 50 million people worldwide, and is the greatest global challenge to health and social care today (Livingston et al., 2017).

Studies have suggested that people with higher levels of education have greater cognitive reserve (Stern, 2012). In other words, the more you use your brain, the more your brain cells are “protected” against damage. Higher levels of education may also indicate higher socio-economic status (SES; Cadar et al., 2018).

However, Cadar et al. (2018) argue that education may not be an accurate indicator of someone’s current SES, as people tend to complete their studies years before developing dementia, and SES can change throughout life.

Hence, they investigated the association between factors linked to SES (education, wealth and area-based deprivation), and the development of dementia. Effects were compared across two age groups to explore differences in risk of dementia between generation.

Intellectually engaging activities could build cognitive reserve.

Methods

The data for this study was gathered from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA), and looked at participants aged 65 and over without dementia and followed them for 12 years, researching the influence of SES on risk of dementia.

SES was determined by individual wealth (self-report of possessions and investments), level of education and area-based deprivation. Dementia diagnosis was made using various methods; a doctor’s diagnosis reported by the participant or family member/caregiver, and a questionnaire on cognitive decline.

To investigate changes in dementia rates over time, researchers compared two groups; individuals born between 1902-1925 versus 1926-1943.

Results

The researchers analysed factors including education, wealth and neighbourhood deprivation to see if any influenced the risk of developing dementia:

Education

- Results suggest a person’s level of education does not increase or decrease the risk of developing dementia

- These findings contrast with suggestions from previous research that lower levels of education are associated with a greater risk of developing dementia (Livingston et al., 2017).

Wealth

- Results show a weak association between the lowest level of wealth and an increased risk of dementia

- However, the certainty of the association the researchers found is not precise and can vary from double the risk to almost no risk at all, therefore we cannot be confident about the results without further research.

Neighbourhood deprivation

- The level of deprivation in a neighbourhood is not associated with an increased risk of residents developing dementia

- However other research has found a link between higher levels of neighbourhood deprivation and lower levels of mental functioning (McCann et al., 2018).

The researchers also wanted to look at differences in risk of developing dementia between generations. The association between lower levels of wealth and increased risk of dementia is stronger in participants born after 1926 (age cohort II) compared to participants born between 1902-1925 (age cohort I).

Additionally, the researchers claim there is a trend of lower rates of dementia diagnoses in age cohort II compared to age cohort I. However, the results from this study alone are not precise enough to have confidence in this finding.

Levels of wealth might be associated with risk of dementia.

Conclusions

Using participants that nationally represent English people aged 65 and over, the study suggests that levels of education and neighbourhood deprivation are not associated with a higher risk of dementia. In contrast, lower levels of wealth are associated with an increased risk of dementia, particularly in people born after 1926.

However, these results do not show strong associations, so further research with precise results is needed before we can accurately answer the question ‘does socioeconomic status affect the risk of developing dementia?’ to apply to public health strategies for dementia prevention.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first long-term study that considers multiple SES (socio-economic status) factors and their influence on the risk of developing dementia. By using data from ELSA, the study was representative of the English population, both in terms of SES and geographic region. Moreover, the researchers considered variables that may indirectly influence the results, like age, gender, marital status and health conditions. However, factors such as ethnicity and the subtypes of dementia were not considered.

Further limitations were found in the way that data was collected. The questionnaire used to determine dementia occurrence was administered by a family member or caregiver of the participant, not a professional, so the information on the participants’ cognitive ability may be inaccurate. Data gathered on wealth was also based on individuals’ self-report (including value of their property and possessions), which may not be completely reliable.

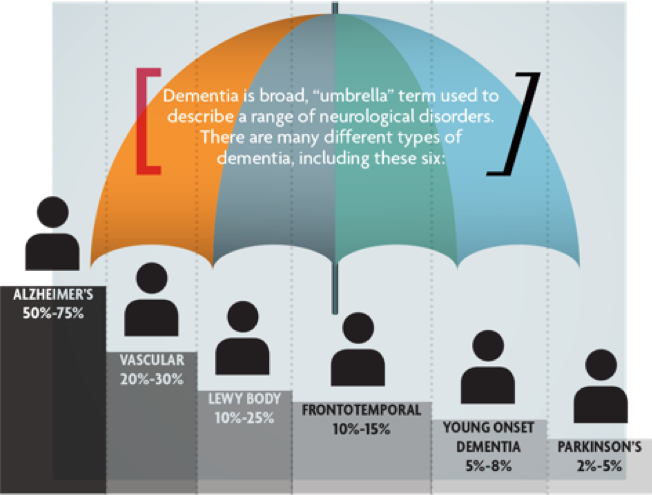

The different types of dementia that were not explored in this study.

Implications for practice

This study suggests that wealth may play a role in the risk of developing dementia. Unfortunately, there is not much you can do to increase your wealth over a short period of time. We can instead look to policy-makers to use findings of present and future research studies to inform policies at a population level.

Reduced taxation among elderly people according to the value of their estate might be one of the first steps towards reducing social inequalities (Schweiger, 2015). Further research could aim to identify the level and specific components of wealth required to help reduce the risk of developing dementia.

We do not yet know whether lifestyle factors related to wealth, such as taking part in cultural activities, could also affect both the risk of dementia (Livingston et al., 2017). Further research in this area is required to inform policy and service provision which aims to reduce social inequality.

On a community level, elderly people could be offered free or subsidised cultural and social activities or be encouraged to take part in mentally stimulating and meaningful activities. In other words, engaging in activities might keep them active, thereby narrowing the gap that different levels of wealth may lead to in their everyday lives.

As there is no disease-modifying cure for dementia currently, public health strategies to prevent or delay the onset of dementia are crucial.

As there is no disease-modifying cure for dementia currently, public health strategies to prevent or delay the onset of dementia are crucial.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Avi Cohen – @AviCo308, Zenia Elshazly, Emily Fisher – @emilyrf2, Mia Maria Günak, Stefanny Guerra Ceballos – @steffgc, Brendan Hallam, Tiffeny James – @TiffenyJames, Anastasia Voutsara – @AVoutsara, Georgia Wilson, Jacquelyn Yang – @jacquelyn_yang.

Conflict of interest

None reported.

Links

Primary paper

Cadar, D., Lassale, C., Davies, H., Llewellyn, D. J., Batty, G. D., & Steptoe, A. (2018). Individual and Area-Based Socioeconomic Factors Associated With Dementia Incidence in England. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(7), 723. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1012

Other references

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., … & Cooper, C. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet, 390(10113), 2673-2734. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

McCann, A., McNulty, H., Rigby, J., Hughes, C. F., Hoey, L., Molloy, A. M., … & McCarroll, K. (2018). Effect of Area‐Level Socioeconomic Deprivation on Risk of Cognitive Dysfunction in Older Adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. doi:10.1111/jgs.15258

Schweiger, G. (2015). Taxation and the Duty to Alleviate Poverty. In Philosophical Explorations of Justice and Taxation: National and global issues. Springer Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13458-1_3

Stern, Y. (2012). Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet Neurology, 11(11), 1006-1012. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6

Photo credits

- Dan Moyle CC BY 2.0

- Dementia Defined

- Photo by Aziz Acharki on Unsplash

[…] Elshazly, Z. Günak, MM. [et al] (2018). Lack of wealth may increase our risk of dementia. [Online]: The Mental Elf. December 12th […]

A very interesting study. However, there have been other studies identifying steps we can take to reduce the likelihood of dementia or slow the progression of the disease, that revolve around health, wellbeing (physical and mental) and social interaction. Surely then poor health and unhappiness will be closely associated with a higher risk of dementia? Perhaps that’s what we should be trying to combat as a society.