We know a lot about the long term consequences for family carers of supporting someone with dementia. Much of this research is cross-sectional, meaning that we only have a snapshot of how carers are managing. However, results from studies in which participants have been followed up over time (for example, Mahoney et al., 2005, Schulz et al., 2010) indicate that there is a ‘wear and tear’ effect whereby carers experience greater stress as time goes on and as the person for whom they care needs more support. This can lead to them finding it more difficult to cope with some aspects of caring than they did previously.

For pragmatic and methodological reasons, most published research has concentrated on carers looking after someone whose dementia has developed after the age of 65. We know much less about the challenges faced by those supporting a person whose dementia developed under the age of 65 (young onset dementia). Research such as this, which has both a longitudinal design and includes carers of people with dementia of all ages is long overdue.

Methods

The study drew on two datasets. The first was derived from the Needs in Young Onset Dementia Study (NeedYD) (van Vliet et al., 2010). It consisted of 219 ‘dyads’ – people with dementia aged 65 and under and their carers – who had been recruited from various services spread across different provinces in The Netherlands.

The second consisted of information about 108 dyads. These were people who had developed dementia after the age of 65 and their carers. They had taken part in an earlier study and had been recruited from memory clinics in Maastricht (de Vugt et al., 2006).

Both studies had been undertaken using a prospective cohort design. This meant that after being recruited to the study, every carer and person with dementia was assessed at six-month intervals over a two year period.

In this article, the focus is on the carers. It mainly consists of data from a number of standardised measures used to establish the carer’s physical and mental health. These included the RAND-36, a well-established measure of health related quality of life (HRQoL) (Hays & Morales, 2001) alongside other information, such as a symptom checklist, a screening test for depression, and a questionnaire about how competent they felt in caring.

The data were analysed using a repeated measures design. This involved comparing the scores of all the people caring for someone with late and young onset dementia across all five time points from when participants entered the study and at each subsequent six-month interval.

Results

Consistent with existing research, carers in both groups experienced high levels of physical and psychological difficulty, depression (although this lessened over time), and decreased feelings of competence. Crucially, none of the differences in scores across the two groups were statistically significantly different with the exception of health related quality of life. People caring for someone with young onset dementia had significantly lower scores than their counterparts caring for someone with late onset dementia. This suggested that their health related quality of life was poorer and that it was unlikely that this difference could be explained by chance alone.

Among the explanations for this was that carers of someone with young onset dementia had never imagined that the person for whom they cared would develop dementia at such an early stage. They were also often reluctant to share the diagnosis with others and tended to avoid social situations, meaning that they felt more socially restricted.

People caring for someone with young onset dementia had significantly lower quality of life scores than their counterparts caring for someone with late onset dementia.

Conclusions

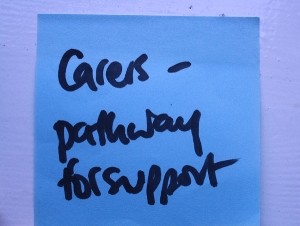

The authors concluded that although carers of people with young and late onset dementia face similar challenges, carers of people with young onset dementia need more targeted support from services to help them combine their caregiving with their other responsibilities.

Strengths and limitations

Although this is a complicated set of data on which to report, the authors give a very clear account of what they have done. They took care to test for factors that could have affected the results in the statistical tests they used. However, in an ideal world, the samples would have been recruited identically and data collection would have taken place at the same time.

In my view, the main limitation is the omission of any data on service receipt. Given the shortage of suitable services for people with young onset dementia, it is possible that the difference in health related quality of life was because people with late onset dementia and their carers had better access to services. The authors also do not appear to have explored other potentially protective factors, such as social support or a strong relationship between the person with dementia and the carer that may have predated, and continued after, the diagnosis. I also wish the term ‘informal’ caregiver in the title had been avoided. However, these points should not detract from the study’s importance as it represents a major step forward in our knowledge.

Would tailored advice have helped carers of people with young-onset dementia?

Summary

Individual carers respond to their situation in different ways. We need to ensure a better fit between the support that is offered and the actual difficulties experienced by the carer and the person for whom they care. For example, the carers in this study reported a low sense of competence in terms of their caregiving. Would this have been different had they had access to tailored advice on possible solutions to the aspects they found most difficult?

At a time when proportionally fewer people receive social care support than in the past (Fernandez et al., 2013), we must become better at predicting which carers are at most risk of becoming so stressed that their own health is affected. Carers and people with young onset dementia face particular difficulties in terms of other events that may be going on in their lives, such as bringing up children, career development, and maintaining financial security. Better access to practical support in these areas is needed.

Online open learning about dementia

People who are interested in dementia, whether as professional or informal carers, may wish to consider enrolling in The Many Faces of Dementia, a free online course being offered by University College London.

The course provides videos by experts and patients, resource materials, interactive exercises and discussions. It starts on the 14th March.

Links

Primary paper

Millenaar, J. K., de Vugt, M. E., Bakker, C., van Vliet, D., Pijnenburg, Y. A. L., Koopmans, R. T. C. M. & Verhey, F. R. J. (2015) The impact of young onset dementia on informal caregivers compared with late onset dementia: results from the NeedYD Study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.07.005.

Other references

de Vugt, M. E., Jolles, J., van Osch, L., Stevens, F., Aalten, P., Lousberg, R. & Verhey, F. R. J. (2006) Cognitive functioning in spousal caregivers of dementia patients: findings from the prospective MAASBED study. Age and Ageing, 35 (2), 160-166. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afj044.

Fernandez, J. L., Snell, T. & Wistow, G. (2013) Changes in the Patterns of Social Care Provision in England: 2005/6 to 2012/13. PSSRU Discussion Paper 2867, Personal Social Services Research Unit, Canterbury.

Hays, R. D. & Morales, L. S. (2001) The RAND-36 measure of health-related quality of life. Annals of Medicine, 33 (5), 350-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/07853890109002089.

Mahoney, R., Regan, C., Katona, C. & Livingston, G. (2005) Anxiety and depression in family caregivers of people With Alzheimer disease: The LASER-AD Study. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 13 (9), 795-801. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200509000-00008.

Schulz, R., Zdaniuk, B., Belle, S. H., Czaja, S. J., Michael Arrighi, H. & Zbrozek, A. S. (2010) Baseline differences and trajectories of change for deceased, placed, and community residing Alzheimer disease patients. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 24 (2), 143-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181b795b7.

van Vliet, D., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., Verhey, F. R. J. & de Vugt, M. E. (2010) Research protocol of the NeedYD-study (Needs in Young Onset Dementia): a prospective cohort study on the needs and course of early onset dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 10 (1), 1-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-13.

Photo credits

Mark Strobl, Flickr, BY CC 2.0

Aka Tman, Flickr, CC BY 2.0

Social Innovation Camp, Flickr CC BY 2.0

Today on the Social Care Elf: the impact of young onset dementia on informal carers https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

Today I write about research comparing carers of people with younger and later onset dementia for @SocialCareElf: https://t.co/KiaHfwUfvb

@Aspirantdiva @SocialCareElf What struck me about this is that us carers tend to get lumped together as if our experiences are the same >

@Aspirantdiva @SocialCareElf > and of course they’re not, even though there maybe similarities. Needs to be more recognition of this.

@welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf Totally 100% agree. At least this study tried to identify different factors for carers in either position

@Aspirantdiva @SocialCareElf Yes we need more studies like this!

@welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf Yes. Sometimes advantage – eg if challenging policies but risk that ‘carer’ identity subsumes everything

@Aspirantdiva @welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf Indeed. I dinnae even get seen as one.

@AlresfordBear @welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf Yes that is another debate – often stereotyped ideas about ‘carers’

@Aspirantdiva @welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf And the placed moral burden by not examining individuality.

@Aspirantdiva @welliesnseaweed @SocialCareElf And say how wonderous carers are and the inherent role is on awareness tours *looks at camera*

@welliesnseaweed @Aspirantdiva @SocialCareElf For example at the weekend my blood pressures shot low instantly…..nearly went.

@welliesnseaweed @Aspirantdiva @SocialCareElf Day after caring lol.

Today @Aspirantdiva blogs about impact on carers of people with young onset dementia compared with later onset: https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

@SocialCareElf @Aspirantdiva Super stuff again.

@Intipton @SocialCareElf Oh how kind Mike! Thank you

Impact of young onset dementia on informal caregivers compared with late onset dementia https://t.co/Lw7LdC3Tii from the Social Care Elf

@Aspirantdiva Carers of people with young onset dementia need more targeted support: https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

Just out today on @SocialCareElf – comparing carers of people with younger and later onset dementia:by @Aspirantdiva https://t.co/mgvQ3EP3wW

Interesting @SocialCareElf #blog by @Aspirantdiva on the effects of young onset #dementia on informal #carers #YOD https://t.co/7848c3Zi5I

Impact of young onset dementia on informal caregivers compared with late onset – @Aspirantdiva on @SocialCareElf https://t.co/wealXLpl9g

[…] 1Impact of Young Onset Dementia on Informal Caregivers Compared with Late Onset Dementia […]

@YoungDementiaUK This won’t be news to you but you may be interested in this @SocialCareElf: https://t.co/mgvQ3EP3wW

@BarbaraStephens @DPCIC Nothing new here Barbara in terms of issues but a bit more evidence in @SocialCareElf: https://t.co/mgvQ3EP3wW

@alzheimerssoc Have you seen @Aspirantdeva’s blog about the needs of carers of people with young onset dementia? https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

Carers of people with young onset dementia had lower quality of life than carers of later onset dementia https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

Evidence from cohort studies about the particular support needs of carers of people with young onset dementia: https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

In case you missed it: @Aspirantdeva on the impact of caring for someone with young onset dementia. https://t.co/mTgYyYWGA3

Impact of young onset dementia on informal caregivers compared with late onset dementia https://t.co/04oxoDh48f