Dementia prevalence is rising globally (Prince, 2015) and the demand for palliative care is therefore likewise expected to increase (Fetherston, Rowley & Allen, 2018).

According to NICE guidelines (2018), palliative care follows a holistic approach that addresses social, psychological, physical and spiritual needs to maximize the quality of life (QoL) of people with dementia at all stages. The provision of palliative care can, for instance, be delivered through pain management, advanced care planning and nutrition.

In their clinical review, Fetherston, Rowley and Allen (2018) summarised the literature on diagnosis, assessment and management of dementia, communication and ethical issues in dementia that should guide the provision of end-of-life palliative care. They also touch on topics, such as goals of care and care homes.

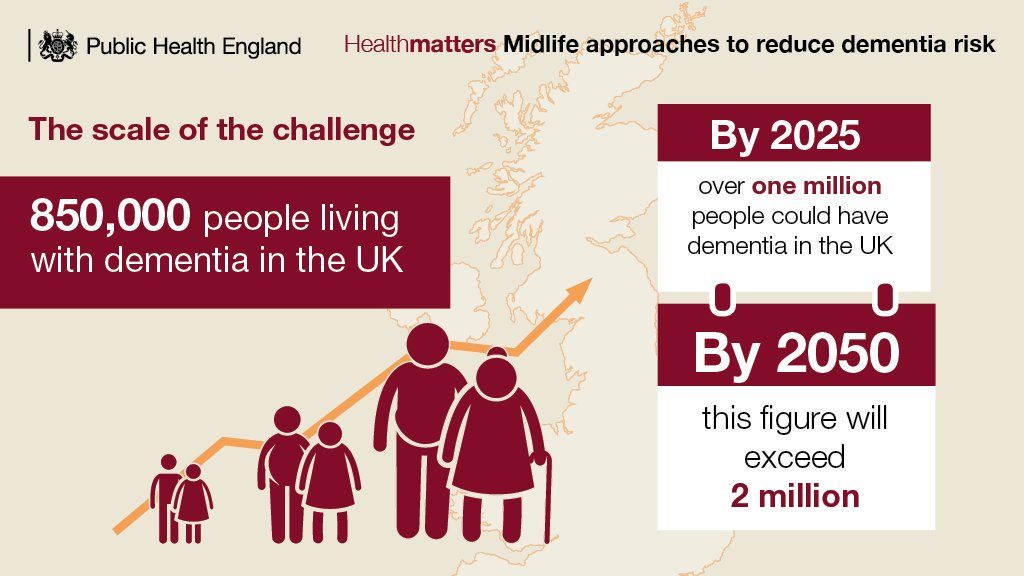

The rise in dementia prevalence in the UK (Public Health England, 2018).

Methods

The authors of this clinical review conducted their search on four databases (PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar and the Cochrane Database) to include a wide variety of literature on this topic. They included studies that were published from 2000 to 2018. The studies were ultimately included based on their clinical relevance and their quality.

Results

Diagnosing dementia

The diagnosis of dementia should follow NICE guidelines, where reversible causes of symptoms are explored, informants are interviewed, and severity of dementia is established. Nevertheless, this process is not specific to end of life care, and even when it is meticulously followed, life expectancy becomes particularly difficult to determine due to other health conditions varying widely among individuals.

Management of symptoms

At early stages, the person with dementia should be asked about future care decisions, which usually involve end of life preferences (e.g. treatment, resuscitation, living arrangements).

As dementia progresses, the goals of care turn to managing symptoms and maintaining quality of life, for instance:

- Pain is a symptom difficult to recognise and thus manage. Medical history can provide important cues, as pain may be due to previous conditions such as arthritis.

- Behavioural issues are usually a sign of unmet need (e.g. constipation, fatigue). If the unmet need causing distress is identified, addressing it can reduce problematic behaviours. Non-pharmacological treatments should be considered first, for example, improving communication or modifying surroundings. Pharmacological treatments like antipsychotics should only be considered in serious cases, and serious thought must be given to side-effects.

- Weight loss is common at advanced stages. Strategies to encourage eating include providing softer or already-cut food, allowing more time to eat and providing support when doing so. Evidence on artificial nutrition indicates it does not extend life nor prevent aspiration pneumonia.

- Infections usually present as an unexplained change in behaviour (e.g. agitation). Decisions to treat infections should align with patient’s goals as treatment might cause discomfort, and should be based on clinical assessment of severity and local antimicrobial use guidelines.

Communication and discussion of ethical issues

Open communication between carers/family and healthcare professionals are important when faced with challenging subjects, and can be improved by involving carers/family in decision-making, sharing information, providing guidance, and being responsive to their needs. Overly aggressive treatments should be avoided and patients’ goals of care are important when considering hospital admission. Providing care such as washing under restraint needs to be appropriately justified and should only be used after exploring other options and perspectives of all caregivers.

Location of care

Most people prefer to die at home, however more and more deaths happen in hospitals or care homes.

- Difficulties in care homes may arise (e.g. lack of staff confidence and training).

- Hospices might not be appropriate for those with severe dementia due to easy access to open space.

- Although hospitals might enable intensive symptom management, they are usually not ideal places of death and should only be used when necessary or preferred. Advanced care planning is key to reducing unwanted admissions.

At early stages, the person with dementia should be asked about future care decisions, which usually involve end of life preferences (e.g. treatment, resuscitation, living arrangements).

Conclusion

The authors emphasise that an individualistic, person-centred approach which incorporates patients’ physical, psychological and spiritual factors should be used. Open communication, shared decision-making involving patients and families, and supporting their needs are key to improving their experiences and to navigating ethical issues.

Strengths and limitations

This clinical review addresses end of life care in dementia, a previously neglected topic (Marie Curie, 2014). It presents assessment and management aspects affecting people with dementia at the end of life beyond physical symptoms, taking a holistic approach which emphasises person-centred care and family involvement. In a clinical review, authors combine their clinical judgement and expertise with evidence from recent literature.

However, the article uses a briefly described non-systematic search method (this is not a systematic review), using only three search terms, which means that the papers included are unlikely to entirely represent all of the current evidence. Furthermore, it is not clear how the quality of the literature was assessed, there is no critical appraisal and the evidence-base is limited.

The need for advanced care planning and the current challenges surrounding individualised decision-making is emphasised, but detailed recommendations for clinical practice are lacking.

Implications for future research

Future research should develop interventions to address challenges including pain and agitation at end of life, improving shared decision making, and supporting carers of people with dementia with effective planning for end of life bereavement support.

People with dementia and their families should be supported to discuss end of life care preferences whilst the people with dementia still have the ability to do so. However, research is needed to address when these discussions should best take place and who should initiate these conversations to help shape evidence-based policy.

People with dementia and their families should be supported to discuss end of life care preferences whilst the people with dementia still have the ability to do so.

Implications for policy

Most deaths related to dementia occur in care homes. This review highlighted the importance of staff training and confidence in administering end of life care.

People with dementia lack access to good quality end of life care, especially when compared to conditions such as cancer (Marie Curie, 2014). Current policy and practice has focused on living well with dementia, but this should not be in place of supporting people to die well with dementia.

People with dementia lack access to good quality end of life care.

Contributors

Thanks to the UCL Mental Health MSc students who wrote this blog: Avi Cohen (@AviCo308), Emily Fisher (@emilyrf2), Tiffeny James (@TiffenyJames), Georgia Wilson, Mia Gunak, Anastasia Voutsara (@AVoutsara), Jacquelyn Yang (@jacquelyn_yang), Zeina El Shazly, Stefanny Guerra (@Steffgc).

Conflicts of interest

None.

UCL MSc in Mental Health Studies

This blog has been written by a group of students on the Clinical Mental Health Sciences MSc at University College London. A full list of blogs by UCL MSc students from can be found here, and you can follow the Mental Health Studies MSc team on Twitter.

We regularly publish blogs written by individual students or groups of students studying at universities that subscribe to the National Elf Service. Contact us if you’d like to find out more about how this could work for your university.

Links

Primary paper

Fetherson, A., Rowley, G. & Allan, C. (2018). Challenges in end-of-life dementia care. Evidence-Based Mental Health.

Other references

BBC Horizon (2019, May). We need to talk about death.

Alzheimer’s Society (2014, November). Dementia UK: Update (second edition).

Marie Curie Cancer Centre (2014, December). Living and dying with dementia in England: barriers to care.

Prince, M. World Alzheimer’s report 2015. London: The Global Impact of Dementia, 2015.

Public Health England (2018). Dementia applying all our health.

NICE (2018) Dementia: assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers.

Photo credits

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

As Frontotemporal is my fate, my mental capacity will be the last destroyed. planning ahead for a dementia ending of my life. I have chosen to get to “Dignitis” Switzerland before I lose the required brain capacity for the dicision to be made.

for a peaceful compassionate ending of my long journey into that end state.I bleive so strongly, that all people diagnosed with a dementia ending , should be given the “dignitis end of life option” As after seeing both my parents die in those end of life dementia wards. WHO would choose that place instead of a peaceful ending of their own choices.

“I have chosen to get to “Dignitis” Switzerland before I lose the required brain capacity for the dicision to be made.”

Be careful. Plan well. There are quite a number of hurdles to overcome if you reach out to Dignitas.

Really helpful article! Like you’ve said, palliative care can be really helpful for patients suffering from dementia. Apart from managing symptoms such as pain and infections, palliative care can provide emotional and spiritual support to patients and their family. There are volunteers who provide companionship to the patients, which is so important with a mentally degenerative disease.