The prevention of self-harm and suicide is one of the primary goals of treatment across all psychiatric disorders. Bipolar disorder has particularly high rates of completed suicides, so prevention of suicide is especially important for this disorder. The question of whether lithium (or another medical treatment) best prevents suicide in bipolar disorder has long been asked, and the preponderance of indirect evidence suggests that it does, although there is great uncertainty about the relative benefit of lithium compared to other drugs when the goal is to prevent self-harm, injury and suicide.

The study under consideration here uses a different approach to answering the question about the relative benefit of different common treatments for bipolar disorder. It examines a large dataset derived from electronic health records (EHR) to determine whether exposure to lithium results in improved outcomes compared to sodium valproate, olanzapine or quetiapine, three commonly used acute and maintenance treatments for bipolar disorder. The authors used a propensity score to adjust for baseline clinical characteristics to try to make the study groups comparable.

The great strength to this approach is that it examines real patients, not those selected for participation in a randomised trial. There is a possibility of bias, however, that may make results from EHR studies difficult to interpret. Confounding by indication (the fact that certain treatments tend to look harmful because they are given to sicker patients, or visa versa) is the biggest barrier to knowing whether the results of this study are biased. Perhaps the patients in one group were inherently different from those in the other groups and therefore a medication was chosen for that reason (rather than that the medication itself caused the difference). Let’s have a look at the study and its results.

Indirect evidence suggests that lithium prevents suicide in people with bipolar disorder better than other medications, but there remains considerable uncertainty about this issue.

Methods

- Cohort study using primary care EHRs (electronic health records) data collected between January 1, 1995, and December 31, 2013, by The Health Improvement Network (THIN) system.

- Individuals (aged 16 and older) with diagnoses of bipolar disorder were included in the study if they received 2 or more consecutive prescriptions for treatment lasting 28 days or longer of lithium, valproate, olanzapine or quetiapine

- Patients were followed from the time of first prescription to 3 months after medication discontinuation (if that occurred). Patients prescribed any of the medications concurrently were excluded from the analyses.

Outcomes

- The primary outcome of interest was emergency department or primary care attendance for self-harm during the period of drug exposure and the 3 months afterward (including intentional poisoning, intentional self- injurious behaviour, and self-harm acts of uncertain intent)

- Secondary outcomes were unintentional injury (e.g., falls or motor vehicle crashes) seen in primary or secondary care or a record of the patient’s suicide during this period.

Propensity score

- Propensity score (PS) adjustment for sex, age at the start of treatment with the study drug, year of entry to the cohort, race/ethnicity, cardiovascular disease diagnosis before baseline, hypertension, chronic kidney disease at baseline, history of hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, history of liver disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, epilepsy, alcohol use (grouped as none or low, moderate or heavy, or dependence), history of illicit drug use, smoking status, body mass index, anxiety symptoms or diagnosis before baseline, depressive symptoms or diagnosis before baseline, sleep disturbance before baseline, treatment with the study drug at or before baseline, and history of previous self-harm.

Results

The authors found a strong association between lithium prescribing and lower risk of self harm:

- Of 14,396 individuals with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, 6,671 were included in the cohort, with:

- 2,148 prescribed lithium

- 1,670 prescribed valproate

- 1,477 prescribed olanzapine

- 1,376 prescribed quetiapine

- Self-harm rates were lower in patients prescribed lithium compared with the other drugs:

- Lithium (205; 95% CI, 175 to 241 per 10,000 person-years at risk [PYAR])

- Valproate (392; 95% CI, 334 to 460 per 10,000 PYAR)

- Olanzapine (409; 95% CI, 345 to 483 per 10,000 PYAR)

- Quetiapine (582; 95% CI, 489-692 per 10,000 PYAR).

The authors also report:

People prescribed lithium tended to be older than those taking other study drugs, with more years of follow-up data. These individuals were less likely to have records of depression, anxiety, or self-harm before entry into the cohort. Individuals prescribed lithium had no more contacts with primary care services during follow-up than individuals prescribed other drugs.

This association [between lithium and self-harm] was maintained after PS adjustment (hazard ratio [HR], 1.40; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.74 for valproate, olanzapine, or quetiapine vs lithium) and PS matching (HR, 1.51; 95% CI, 1.21 to 1.88). After PS adjustment, unintentional injury rates were lower for lithium compared with valproate (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.58) and quetiapine (HR, 1.34; 95% CI, 1.07 to 1.69) but not olanzapine. The suicide rate in the cohort was 14 (95% CI, 9-21) per 10,000 PYAR. Although this rate was lower in the lithium group than for other treatments, there were too few events to allow accurate estimates.

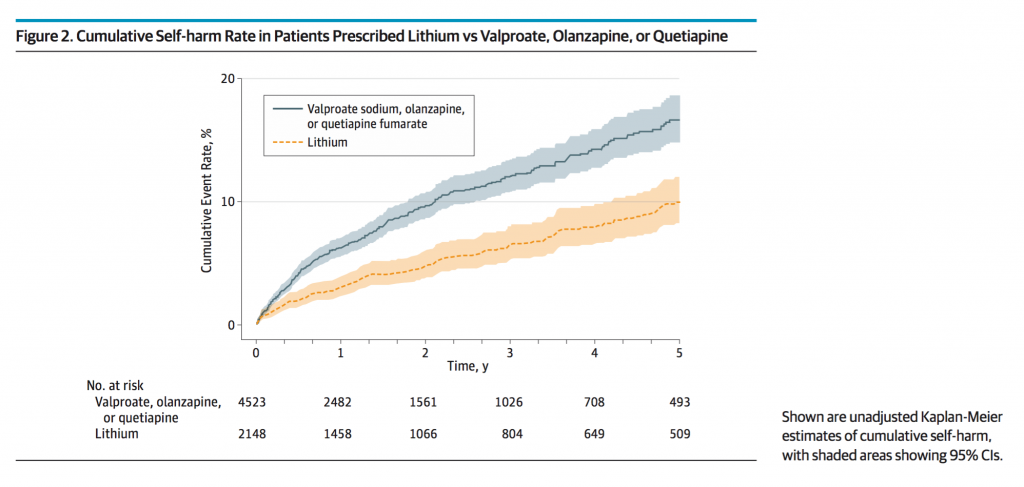

The authors include this figure, showing the risk over time of self-harm (the cumulative self-harm rate) of the unadjusted model rather than the PS adjusted model:

Is lithium viewed as a risky drug?

Consistent with what has been reported in the literature, lithium is associated with lower rates of self-harm in patients with bipolar disorder compared to the rates found in patients treated with valproate, olanzapine, or quetiapine. There remains a great deal of uncertainty, though, about all the differences as to why drugs were differentially prescribed and whether adjusting for them using propensity scores is adequate to statistically create groups that are as unbiased as those that would be arrived at through randomisation.

Clinicians likely make very complex determinations of risk and benefit when making prescribing decisions. It is quite possible, though, that prescribers view lithium as a risky drug (because of its risk of both accidental and intentional overdose) compared to the other drugs examined in this study (whose risks in overdose are considerably lower), and therefore are prescribing lithium to lower risk patients to begin with.

There certainly may be reasons for this. Lithium has a very narrow therapeutic window and must be monitored closely in the context of other medications (NSAIDs and diuretics, for example) and medical problems. Even if lithium is a drug that (as the authors suggest) reduces impulsive aggression, it is not likely being prescribed as readily to patients who are perceived by clinicians to have that problem in the first place. The baseline characteristics of the sample suggest as much: the sample, among other things, is older (younger people tend to be more impulsive), less likely to have had prior self-harm (in spite of being older and therefore having extra years before treatment to have harmed themselves), less likely to be cigarette smokers (itself associated with impulsiveness), and less likely to be anxious or depressed.

All of this suggests that lithium is being prescribed to a lower risk group to begin, and makes it very difficult (even with propensity score matching) to conclude that it is the lithium itself, rather than baseline differences in groups, that is reducing the risk. The propensity score matching markedly reduces the differences in risk between the lithium group and the others, and it is difficult to know whether the differences would be even further diminished (towards the null) if all factors actually involved in prescribing differences (such as actual measures of impulsiveness) were included in the propensity score.

Prescribers may view lithium as a risky drug and therefore only prescribe it to lower risk patients to begin with.

Conclusion

The authors conclude that:

Lower rates of self-harm in those prescribed lithium may be due either to improved mood stabilization compared with other treatments or specific effects on impulsive aggression and risk taking.

An alternative conclusion, not addressed by the authors, is that even at baseline, lithium is being preferentially prescribed to a lower risk group.

Implications

How this study might be most appropriately used is to increase the dissemination of evidence about the importance of more widespread lithium use. I, for one, am for more lithium prescribing. There is much more randomised data supporting its use in general in bipolar disorder than for many other drugs, and its prescribing is, contrary to what the evidence might necessitate, declining. People are afraid of it. There are no data, in fact, to support its being associated with more death from all causes; to the contrary, the opposite is true.

Lithium, in this cohort, is clearly being preferentially kept from more severely ill patients with higher risk of self-harm (as the baseline characteristics confirm), but much indirect evidence suggest that the converse should be true. Even if this study is not definitive, the preponderance of the evidence suggests that lithium mitigates risk of self-harm and suicide, and none, most importantly, suggests that it increases such risk. Continued education about lithium prescribing, the absolute and relative risks to patients of its use, and support to practitioners and patients alike must be stressed.

There is also a call to actually do comparative trials. The Veterans Administration, in the United States, is currently undertaking the largest randomised trial of lithium for suicide prevention ever undertaken, expecting to randomise 1,862 Veterans with depression (from both bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder) to either adjunctive lithium or placebo, and to follow them for up to a year. When completed, this study has the potential to add considerable information regarding just the question we are asking today.

This new study adds further weight to the case for more widespread lithium use in people with bipolar disorder.

Links

Primary paper

Hayes JF, Pitman A, Marston L, Walters K, Geddes JR, King M, Osborn DP. (2016) Self-harm, Unintentional Injury, and Suicide in Bipolar Disorder During Maintenance Mood Stabilizer Treatment: A UK Population-Based Electronic Health Records Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 1;73(6):630-7. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0432.

Other references

Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J. (2003) Lithium treatment and suicide risk in major affective disorders: update and new findings (PDF). J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64 Suppl 5:44-52.

Cipriani A, Hawton K, Stockton S, Geddes JR. (2013) Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013 Jun 27;346:f3646. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3646. Review.

Ostacher MJ, Nierenberg AA, Perlis RH, Eidelman P, Borrelli DJ, Tran TB, Marzilli Ericson G, Weiss RD, Sachs GS. (2006) The relationship between smoking and suicidal behavior, comorbidity, and course of illness in bipolar disorder (PDF). J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 Dec;67(12):1907-11.

Photo credits

Lithium for bipolar disorder: the best maintenance mood stabiliser protection… https://t.co/TnV3jdDh31 #MentalHealth https://t.co/SCVw3cnwSy

Today @RecoveryDoctor on self-harm, unintentional injury & suicide in bipolar disorder during maintenance treatment https://t.co/3v3GV8AnIp

Lithium for bipolar disorder: self-harm and suicide https://t.co/ZXhD4LeOKe

While lithium may well be the ‘best’ option, for anger, mood stablisation etc.

It is a heavy metal, something that we are told we should do everything to avoid. Look at the close monitoring required to ensure the patient isn’t poisoned! Can it really be the ‘best’ option, especially if you talk long term effects?

We are told as mental health patients we have a 15 – 20 year shorter life expectancy, are drugs like this part of that? That never seems to be researched or talked about, it’s always ‘well you have to take it, the benefits out way the side effects’, well do they really?

Hi Thorvid,

I don’t think lithium is a perfect option. Or necessary the best available option for all individuals with bipolar disorder. I do think we need to be considering using it more frequently than we currently do. There is actually some (low quality, observational) evidence that people taking lithium live longer than those with bipolar disorder who don’t.

I think you are right that we need to break down what ‘best’ means:

1. There is overwhelming evidence that lithium is the most effective mood stabiliser

2. There is evolving evidence that it reduces self-harm, and suicide

So then, we need to think about:

3. Adverse effects

We recently published a paper examining rates of the main adverse effects of the most commonly used mood stabilisers (it is available open access here: http://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1002058 and was discussed in this recent article in the guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2016/aug/14/lithium-should-be-more-widely-used-for-bipolar-disorder-researchers-say). It suggests that although impaired renal function is more common in people taking lithium, severe renal failure is as rare as it is in those taking other mood stabilisers. Conversely people prescribed lithium were far less likely to experience considerably weight gain (>15%) and clearly weight gain is associated with a number of bad outcomes. I hope that this paper will help clinicians and individuals with bipolar weigh up the benefits and risks together.

Thank you for your reply, and being frank about the reality that there is actually an other side to medication.

It is so often brushed under the table, (even more so in the mental health arena), and patient concerns are meant with ‘your being dificault’, ‘you don’t want help’, ‘you don’t know what’s best for you, your ill’.

We as patients need such concerns to be taken seriously and for open discussions on the subject, that continue throughout treatments, as opinions can change. So I thank you for allowing this to happen and being engaged.

Morning @in_psych We’ve blogged about your recent @JAMAPsych study on #bipolar #lithium #selfharm. Any comments? https://t.co/3v3GV8AnIp

#Lithium for #bipolar disorder: best maintenance protection against selfharm & suicide? https://t.co/QXSErw5InL @Mental_Elf on #cohortstudy

I am very pleased that Professor Ostacher and The Mental Elf were interested in our study, and I hope that the Veterans Administration trial of lithium for suicide prevention, for which Professor Ostacher is an investigator, will put pay to any doubt about the answer to this question. In the meantime, I believe this study is part of the best available evidence we have about the anti-self-harm properties of lithium. I agree that the key limitation in any pharmcoepidemiological study of this type will be the risk of confounding by indication. With the use of a propensity score, accounting for multiple reasons for prescribing choice, and in the study design itself we attempted to minimise this problem. In the end though, it comes down to how well you as the reader believe statistical models can achieve baseline covariate balance (that is, remove confounding).

The main concern raised is that individuals prescribed lithium were likely to be less impulsive, with lower risk. This might be suggested from the baseline characteristics: for example, patients prescribed lithium tended to be older, less likely to have histories of prior self-harm, and were less likely to smoke. They do not, however, have more frequent moderate or heavy alcohol use (which would also be associated with impulsivity). If we agree that each of these factors is associated with impulsivity, then they act as proxies for impulsivity in the statistical model. To dramatically alter the conclusions, there would need to be an unmeasured confounder that was independently associated with prescribing choice and self-harm (and not related to any other confounders in the model). Also, the balancing nature of the propensity score means that these characteristics should be very similar in each matched pair in the analysis. We spent considerable time developing the propensity score to account for potential confounding by indication, as we were aware this is always going to be a potential criticism. No routine data source will contain a direct measure of impulsivity, and so this would only be achievable in the context of an RCT or a smaller prospective cohort study.

I’m not going to argue that this study should replace a well carried out RCT, but it does have benefits in terms of generalisability, time and cost. It is hard to recruit people who have a history of self-harm or suicide attempt, and let us not forget that the BALANCE trial of lithium vs. valproate took seven years to recruit 345 randomised subjects, having initially been conceived for a sample size of 3,000. There is nothing to suggest that the results are invalid; the conclusions are in line with the limited amount of existing trial evidence we have, and results from previous observational studies (often smaller, less well accounting for confounders, less generalisable). In addition, as far as I am aware, this study is the first to describe accidental injury rates in individuals taking common mood stabilisers. This is important because, as well as an increased risk of suicide, individuals with bipolar disorder have a risk of death from accidental injury 6 times that of the general population.

Recently, professional bodies such as the British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP) have started to view this type of study more favourably, with the BAP prescribing guidance for bipolar disorder stating: “In the past such data would have been rated inferior to RCTs as a matter of principle. However, the quality and scale of some routinely collected data sets can provide relatively unbiased and reliable evidence for the effectiveness and safety of a treatment. While non-randomised, such evidence is more convincing than any but the highest quality RCTs, and with superior external validity”.

Another point Professor Ostacher touches on is the failure of clinicians to respond, in terms of their prescribing practice, to the evolving evidence base for lithium. I hope that this blog can contribute to improving the evidence based care of people with bipolar disorder.

Great comments from @in_psych on our #bipolar blog today!

Join the discussion here: https://t.co/3v3GV8AnIp

@RecoveryDoctor

Lithium for bipolar disorder: self-harm and suicide https://t.co/wPD3XZCEN1

New study adds further weight to the case for more widespread lithium use in people with bipolar disorder https://t.co/3v3GV8AnIp

@Mental_Elf Unless they have poor tolerence!

Prescribers may view lithium as a risky drug & only prescribe it to lower risk patients https://t.co/3v3GV8iMjP https://t.co/aiaTCyamr3

[…] Lithium for bipolar disorder: the best maintenance mood stabiliser protection against self-harm and … – Consistent with what has been reported in the literature, lithium is associated with lower rates … […]

RT @Mental_Elf: Does #lithium prevent suicide in ppl w #bipolar better than other drugs? @RecoveryDoctor on recent @in_psych study https://…

Don’t miss:

#Lithium for #bipolar disorder

Best protection against self-harm & suicide?

https://t.co/3v3GV8AnIp https://t.co/5KExRvDxfG

@Mental_Elf I can say I was SH daily went on lithium Feb stopped within days. SH once this month.

Lithium for bipolar disorder: best maintenance mood stabiliser protection against self-harm & suicide? https://t.co/5tyFYbra5L

[…] Lithium for bipolar disorder: the best maintenance mood stabiliser protection against self-harm and … – Propensity score (PS) adjustment for sex, age at the start of treatment with the study drug, … […]

Lithium for #bipolar disorder: self-harm and suicide – https://t.co/kdrqWx8wwA

[…] Lithium for bipolar disorder: the best maintenance mood stabiliser protection against self-harm and … – (2016) Self-harm, Unintentional Injury, and Suicide in Bipolar Disorder During Maintenance … […]

[…] Lithium for bipolar disorder: the best maintenance mood stabiliser protection against self-harm and … – Propensity score (PS) adjustment for sex, age at the start of treatment with the study drug, … […]