Many young people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also have Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Evidence from the clinical setting suggests as many as 34% of people with ASD also meet the criteria for ADHD.

Having both of these conditions is associated with greater impairment in adaptive (i.e., everyday) functioning and poorer health-related quality of life.

Although pharmacological ADHD treatments are widely used in this population, there is limited high quality evidence about their effects in the sub-group of young people who also have ASD.

This review (Rodrigues et al, 2020) is needed because:

- psychotropic prescription rates are increasing in children diagnosed with ASD

- drug treatments are used for longer periods than there is evidence for

- rates of polypharmacy in children with ASD are high

- a variety of medication classes are being prescribed, without established evidence to support their use

- previous guidance and systematic reviews were conducted in 2012 and need updating.

Research questions

- In young people with ASD and ADHD, do psychotropic medications improve ADHD symptoms?

- What are the rates of side effects with medication treatment?

- Does medication treatment improve important outcomes other than ADHD symptoms (e.g., family interactions, quality of life)?

Evidence suggests that about 1 in 3 people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also meet the criteria for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), but there’s limited evidence about the safety and effectiveness of drug treatments used widely in this population.

Methods

The review protocol was registered in advance and conformed to best practice for planning and reporting systematic reviews (PRISMA guidelines).

The search strategy was exhaustive, combining database searches across different disciplines with hand searching of reference lists and direct contact with researchers to ask for data.

Inclusion criteria

The review (Rodrigues et al, 2020) looked for randomised trials published since 1992, which looked at:

- Population: < 26 years, diagnosed with a pervasive developmental disorder or ASD

- Interventions: amphetamine salts and methylphenidate-based stimulants, atomoxetine, alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonists, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, bupropion, modafinil, or venlafaxine

- Comparisons: placebo, behaviour therapy (BT) or medications as above

- Outcomes:

- Primary: ADHD core symptoms

- Secondary: Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scales, Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) symptoms, family interactions, quality of life (QoL), cognitive functioning, adverse events.

The reviewers excluded studies using medication in combination with other treatments (e.g., behaviour therapy (BT)).

There was blind, independent selection and quality assessment of studies. The findings were combined in a meta-analysis. The reviewers planned various subgroup and sensitivity analyses to explore whether the results were affected by the quality or methods of the studies.

Results

25 studies were included in the review, with a total of 1,257 patients. Participants were from a broad range of ages (3 to 18), over 80% were male.

The most-used assessment tool was ABC-H, the Aberrant Behavior Checklist-Hyperactivity Subscale. However, many different measures were used, and most studies used more than one method of scoring ADHD symptoms.

The Standardised Mean Difference (SMD) allows researchers to compare the effects across different scales like this. What you do is compare the mean change in score between the experimental and control groups.

Obviously, we wouldn’t expect these to be identical. Other measures such as Cohen’s d then allow researchers to estimate whether the difference between the means is important (literally, “small”, “medium” or “large”), and likely to be caused by the treatment and not by chance.

Using the SMD, looking across the different outcome scales used, the reviewers found:

| Drug | Trials | N | Follow-up (weeks) | Summary of effects | Evidence quality |

| Methylphenidate | 4 | 117 | 1-2 | Medium effects on hyperactivity, small effects on inattention | Low: very short-term, small sample size |

| Atomoxetine | 4 | 237 | 6-24 | Small effects on hyperactivity, inattention | Low: short-term, small sample size |

| Guanfacine | 1 | 62 | 8 | Large effects on hyperactivity | Very low: short term, small sample size |

| Aripiprazole | 4 | 493 | 8-42 | Medium effects on hyperactivity | Low |

| Aripiprazole vs Risperidone | 2 | 103 | 8-24 | No effects | Very low: small sample size |

| Lurasidone | 1 | 150 | 6 | No effects | Low: short-term |

Side effects of medication

A range of adverse events were reported across all treatments, including some serious events.

The side effects profile of different treatments is summarised below:

- Methylphenidate: decreased appetite, sleep disturbance; risk was higher with higher doses

- Atomoxetine: decreased appetite, abdominal discomfort and nausea

- Guanfacine: drowsiness and fatigue

- Second-generation antipsychotics: gastrointestinal effects, drowsiness, tremor, drooling and weight gain.

See Table 2 in the published review for more details.

According to the reviewers, this meta-analysis “supports the efficacy and tolerability of methylphenidate or atomoxetine for treatment of ADHD symptoms in children and youth with ASD”. However, the quality of the including studies is “low” or “very low”, so there is an urgent need for better evidence to inform clinical decision making.

Conclusions

This is a well-conducted review that highlights the limitations of research in this area.

Although the results appear both statistically significant and clinically important in favour of drug treatments, we should still consider whether the benefits are worth the potential harms and/or costs. The evidence, broadly, is of low quality, and does not tell us about long-term outcomes, nor effects beyond ADHD symptoms.

A shared decision-making process should be undertaken whereby the strengths and limitations of the evidence-base are weighed with families to help them make informed decisions around choice of medications and length of treatment.

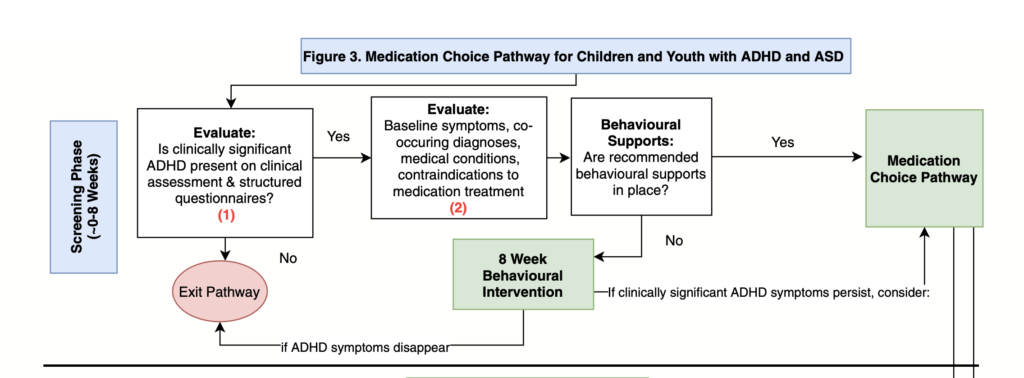

This study, and the accompanying clinical pathway, provides a useful, evidence-based guide to that process.

The review contains a Medication Choice Pathway for Children and Youth with ADHD and ASD, but it’s not open access.

Strengths and limitations

It’s unlikely that the reviewers missed any important published evidence with their search strategy. However, there may be unpublished evidence, which was not included in their review. It’s especially common for small negative studies to be unpublished.

In general, the quality of studies was low. This means there is a higher risk of bias than we would like. The areas of concern are:

- Absence of long-term follow-up (e.g., typically 1-2 weeks for methylphenidate)

- Possible selection bias from shortcomings in randomisation or allocation concealment

- Pharmaceutical industry funding, which may introduce a conflict of interest

- Lack of blinding of interventions and outcome measures.

That said, the results of the studies were broadly consistent. The researchers detected some important heterogeneity in the methylphenidate studies, but felt that this could be accounted for by the different dosing regimens in these trials.

Prescribing of medication for ADHD symptoms in young people with ASD is currently based on low quality evidence with a high risk of bias.

Implications

There is good evidence to believe that drug treatments can decrease the severity of ADHD symptoms in children and youth with ASD, at least in the short term.

However, there is an urgent need for long-term studies of the effects of drug treatments for ADHD in people with ASD. These trials should include outcomes that are important to the young people themselves, as well as their carers. They should also include other clinical outcomes such as ODD, adaptive functioning and, of course, adverse events or side effects.

It is possible to address such questions with retrospective observational studies, although the risk of confounding would be too high to rule out serious adverse outcomes. Really we need proper funding from independent sources for conducting prospective cohort studies.

Further trials of drug treatments for ADHD in people with ASD should include outcomes that are important to young people themselves.

Conflicts of interest

None.

#CAMHScampfire

Join us around the campfire to discuss this paper

The elves are organising an online journal club to discuss this paper with the author Dr Stephanie Ameis, an independent expert (Prof Samuele Cortese), a young person and our good friends at ACAMH (the Association of Child and Adolescent Mental Health). We will discuss the research and its implications. The webinar will be facilitated by André Tomlin (@Mental_Elf).

The focus will be on critical appraisal of the research and implications for practice. Primarily targeted at CAMHS practitioners, and researchers, ‘CAMHS around the Campfire’ will be publicly accessible, free to attend, and relevant to a wider audience.

It’s taking place at 5-6pm BST on Monday 25th May and you can sign up for free on the ACAMH website or follow the conversation at #CAMHScampfire. See you there!

Links

Primary paper

Rodrigues, R., Lai, M-C., Beswick, A., Gorman, D.A., Anagnostou, E., Szatmari, P., Anderson, K.K. & Ameis, S.H. (2020), Practitioner Review: Pharmacological treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatr. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13305.

Other references

Effective Public Health Project Practice (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies

Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation: Making it safe and sound. King’s Fund 2013. ISBN: 978 1 909029 18 7

PROSPERO Record: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=52610