Aggressive challenging behaviour includes verbal aggression, physical violence, sexual aggression, self-injurious behaviour and property damage. These behaviours in people with intellectual disability are a relatively common occurrence and are known to impact quality of life, increase economic costs and often result in exclusion from activities (Richings et al., 2011; Sheehan et al., 2015).

Despite it being a commonly occurring issue, practitioners have yet to decide on a consistent, implementable approach to managing challenging behaviours caused by intellectual disability or cognitive impairment such as verbally or physically threatening behaviour (Van Den Bogaard et al., 2018).

Historically, psychotropic medication has been used as the main intervention, however, this has a relatively poor evidence base and is known to cause a high burden of side effects. Many adults with intellectual disability are prescribed antipsychotic medication without any diagnosed mental illness (Sheehan et al., 2015). Psychological interventions, for example Positive Behavioural Support have shown promising results, however, there is a paucity of high-quality supporting data (Hassiotis et al., 2018; Gore et al., 2013). This paper attempts to systematically dig deeper into current interventions whilst acknowledging the significant complexity involved.

Challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability is common yet we do not have a consistent approach to interventions beyond medication.

Methods

The authors used a realist review approach, which addresses ‘what works, for whom, under what circumstances and how’ (Wong et al., 2016). The process involves developing a scope and initial theory, conducting a literature search, extraction and analysis of the findings before developing a final programme theory. The RAMESES-II standards for analysis and reporting were used to guide the process (Wong et al., 2016). The iterative approach means that the authors repeatedly reviewed the findings with the intention of improving them. An expert panel of nine stakeholders were involved during the process to ‘ensure the results were relevant to the clinical context of this population’ (p.3). The inclusion criteria were broad and included findings from other population groups, for example dementia, adults with mental illness and young people with conduct problems, across a range of settings. In the later stages of the review, the authors also thematically analysed six stakeholder interviews from healthcare professionals, carers and service managers to test and validate the emerging theories.

Results

The results offer a detailed look into the effectiveness of a range of interventions. 59 studies were included in the review, 37 of which focussed on individuals with intellectual disability, 10 on neurotypical individuals with mental illness, eight on people living with dementia, two with behavioural disorders, and two on individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Six of the studies included just children or adolescents. Most studies were from the UK (n=30), and most used an experimental design (n=30). A total of 34 papers were judged to be both ‘highly relevant and rigorous’.

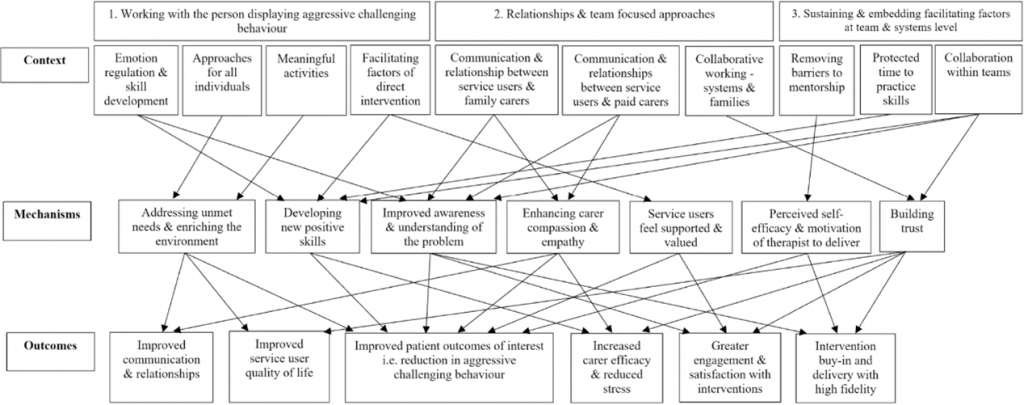

From the data analysed, three main areas of intervention were identified as having significant impacts: Direct interventions (working with the person displaying aggressive challenging behaviour), relationship dynamics (relationships, and team focused approaches), and system-level interventions (embedding and sustaining facilitating factors at team and systems levels).

1. Direct interventions

Interventions focusing on emotion regulation and skill development showed positive results. For individuals with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities, programs that included training in recognising emotional triggers and managing responses were particularly effective. Training for sensory stimulation was proposed to result in a calmer environment and a reduction in aggressive challenging behaviour. Engagement in meaningful activities and personalising interventions were identified as valuable strategies. The duration of intervention varied across studies, with a suggestion that longer treatment durations may be helpful for those with impaired cognitive ability. The sample sizes in the studies varied, with some including as few as 20 participants, while larger studies included up to several hundred.

2. Relationship dynamics

The results underscored the importance of communication and relationship-building between caregivers, paid staff and individuals with aggressive challenging behaviour. Interventions that included training for caregivers on how to communicate more effectively and manage stress improved the overall environment and reduced instances of aggressive behaviour. Themes of respect, non-judgemental practice and collaboration with the person are proposed as improving outcomes.

3. System-level interventions

Changes at the organisational level, such as implementing training programs and creating roles for intervention champions showed promise in sustaining the benefits of direct and relational interventions over time. Protected time to practice and learn skills, and cohesive working with shared responsibility were identified as potential helpful interventions to sustain and embed change at team and systems levels.

The final programme pathway incorporates all the theories and includes skill building, addressing unmet needs, improving understanding of aggressive challenging behaviour, and enhancing motivation, skill and understanding of carers. The pathway suggests the outcomes will be improved communication and relationships, improved service user quality of life, reduction in aggressive challenging behaviour, increased carer efficacy and reduced stress, greater engagement and satisfaction with interventions and intervention buy-in and delivery with high fidelity.

Three main areas of intervention were identified as having significant impacts on challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: Direct interventions, relationship dynamics, and system-level interventions. [View full-sized image]

Conclusions

- The review concludes that effective management of aggressive behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities requires personalised interventions, robust caregiver relationships, and sustained system-level support.

- Key findings highlight the need for interventions tailored to individual emotional and cognitive capabilities and underscore the importance of enhancing caregiver communication and relational skills.

- System-wide changes, such as ongoing training and support for staff, are crucial for maintaining the benefits of these interventions.

- The authors noted, “Interventions must be adaptive to individual needs and supported by an environment that fosters consistent and informed caregiver practices to see a meaningful reduction in aggressive behaviour.“

- This comprehensive approach seems to be essential for long-term success in managing challenging behaviours.

A comprehensive, personalised approach is crucial to success in managing challenging behaviours in adults with intellectual disability

Strengths and limitations

The review presents a robust methodology, leveraging a rapid realist review approach guided by RAMESES-II standards, which strengthens the reliability of the conclusions drawn. The pragmatic approach is described as common in realist reviews, and may be helpful to broaden findings, but may impact the implications for clinical practice, when compared to other systematic approaches such as meta-analysis.

While the review was comprehensive, the decision to include studies from different settings and varying populations may affect the generalisability of the findings. There is a paucity of studies available using experimental methodology in adults with intellectual disability which the authors acknowledge, and therefore broadening the inclusion criteria is reasonable and in many ways a strength of the study. However, it remains important to remember that people with intellectual disability often have different experiences to other individuals with aggressive challenging behaviour. An older person with aggressive behaviour in dementia may not respond to the same interventions as a young adult with Prader-Willi syndrome for example.

As is often the case with reviews, there is a lack of standardisation in how interventions were implemented and measured. This complicates the authors’ capacity to draw firm conclusions about the value of certain approaches. Given the complex nature of behavioural interventions and the subjective measures often used to assess outcomes, there is a risk of observer bias. The reliance on self-reported data or assessments by individuals close to the intervention might influence the reported effectiveness.

The review includes research from a broad range of individuals with aggressive challenging behaviour.

Implications for practice

From the perspective of a psychiatrist specialising in intellectual disability, the findings of this review resonate deeply with my clinical experiences. Often, I find myself in situations where medication becomes a primary intervention for managing aggressive behaviours due to the lack of readily available and robust psychological intervention programs. This reliance on pharmacological solutions, while sometimes necessary, is not always ideal, especially considering the potential side effects and the variability in individual responses to medications. Health and social care systems are often fragmented with practitioners in each camp strongly advocating for the other to pick up the slack. My experience is that this results in the adoption of risk mitigation interventions such as restrictive practices, hospitalisation, or medication, and increases the unmet needs for the individual, which further contribute to deterioration in behaviours. Psychosocial interventions (e.g. positive behaviour support) are gaining traction as an alternative to restrictive practices and psychotropic use, however, we still lack a strong evidence base for their use (Hassiotis et al., 2018).

The authors draw on a broad range of research to generate their programme theory pathway. This is inherently useful to guide the next steps for research. They also neatly summarise the benefits of approaches currently being used. However, they do not tell me what I should not be doing, nor do they provide compelling experimental evidence of any particular intervention here. Despite this, the paper adds weight to the pragmatic approaches that emphasise individualised care, engagement of those around the person and the need for systemic change. Future studies should aim to standardise intervention protocols and outcome measures to provide clearer, more actionable data. Research into the long-term effects of these interventions, as well as their cost-effectiveness, would also be valuable for shaping future care strategies.

Policymakers should recognise the need for funding and resources to support the ongoing training and development of staff. This review highlights the importance of systemic support to ensure that interventions are not only introduced but maintained effectively over time. Policies should facilitate regular review and adaptation of care practices to keep them relevant and effective, incorporating the latest research findings.

All stakeholders will benefit from a more sophisticated approach to challenging behaviour. Research and resulting interventions should reflect this complexity and this paper is an important and wise contribution in the right direction.

What should clinicians not be doing when it comes to dealing with challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities?

Statement of interests

I am an intellectual disability psychiatrist in New South Wales, Australia. I have authored research on challenging behaviour in people with intellectual disability, co-authors have included members of the research team involved in this paper (AH, AS), (Smith, J. et al. 2022)

Links

Primary paper

Royston, R., Naughton, S., Hassiotis, A., Jahoda, A., Ali, A., Chauhan, U., … & Rapaport, P. (2023). Complex interventions for aggressive challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: A rapid realist review informed by multiple populations. PLoS one, 18(5), e0285590.

Other references

Gore, N. J., McGill, P., Toogood, S., Allen, D., Hughes, J. C., Baker, P., … & Denne, L. D. (2013). Definition and scope for positive behavioural support. International Journal of Positive Behavioural Support, 3(2), 14-23.

Hassiotis, A., Poppe, M., Strydom, A., Vickerstaff, V., Hall, I. S., Crabtree, J., … & Crawford, M. J. (2018). Clinical outcomes of staff training in positive behaviour support to reduce challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disability: cluster randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(3), 161-168.

Richings, C., Cook, R., & Roy, A. (2011). Service evaluation of an integrated assessment and treatment service for people with intellectual disability with behavioural and mental health problems. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 15(1), 7-19.

Sheehan, R., Hassiotis, A., Walters, K., Osborn, D., Strydom, A., & Horsfall, L. (2015). Mental illness, challenging behaviour, and psychotropic drug prescribing in people with intellectual disability: UK population based cohort study. Bmj, 351.

Sheehan, R., Mutch, J., Marston, L., Osborn, D., & Hassiotis, A. (2021). Risk factors for in-patient admission among adults with intellectual disability and autism: investigation of electronic clinical records. BJPsych Open, 7(1), e5.

Smith, J., Baksh, R. A., Hassiotis, A., Sheehan, R., Ke, C., Wong, T. L. B., … & PETAL Investigators. (2022). Aggressive challenging behavior in adults with intellectual disability: An electronic register-based cohort study of clinical outcome and service use. European Psychiatry, 65(1), e74.

van den Bogaard, K. J., Nijman, H. L., Palmstierna, T., & Embregts, P. J. (2018). Characteristics of aggressive behavior in people with mild to borderline intellectual disability and co-occurring psychopathology. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 124-142.

Wong, G., Westhorp, G., Manzano, A., Greenhalgh, J., Jagosh, J., & Greenhalgh, T. (2016). RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. BMC medicine, 14, 1-18.

Photo credits

- Photo by Michał Parzuchowski on Unsplash

- Photo by Hiki App on Unsplash

- Photo by Mario Purisic on Unsplash