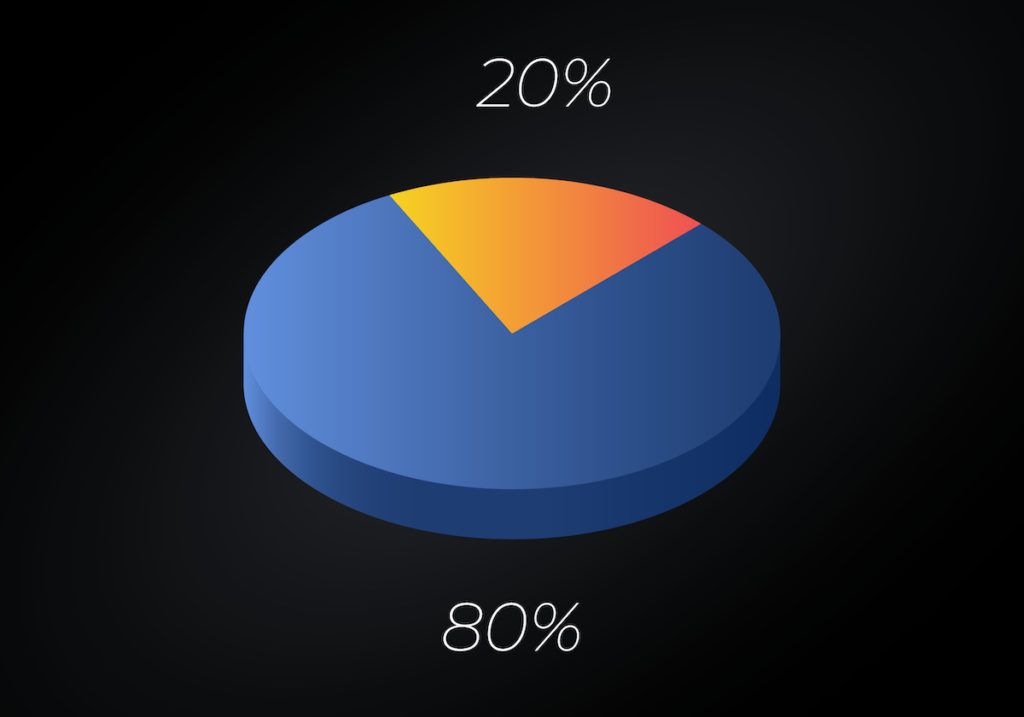

According to the charity Autistica, 80% of autistic people will experience mental health difficulties in their lifetime, making mental illness far more common in autistic individuals compared to non-autistic people. It is therefore likely that psychiatrists will have autistic people on their caseloads, perhaps many.

The role of psychiatrists in the healthcare of autistic individuals could be multifaceted. It may involve recognition and diagnosis, or longer-term assessment and management.

This online survey aimed to explore psychiatrists’ self-reported knowledge about autism and their confidence in making diagnostic or management decisions (Crane et al, 2019).

80% of autistic people will experience a mental health difficulty in their lifetime.

Methods

This online survey collected detailed background information to ascertain information such as number of children or adults with autism under their care, and personal experience of autism.

Part two focused upon the diagnostic process for patients suspected to have an autism spectrum condition, requiring information about whether they followed a standardised procedure for diagnostic assessments.

Part three was comprised of 22 statements used to assess the psychiatrists’ knowledge of autism in three domains: early signs, descriptive characteristics, and co-occurring behaviours.

Part four used a self-efficacy scale to assess the psychiatrists’ confidence in the screening, diagnosis and management of their autistic patients.

Finally, optional free-text boxes were supplied to allow respondents to give further information.

Results

Of the 172 final respondents, there was a broadly even gender split, average age was 48, and the group was largely of White ethnic origin. The majority worked in the public health sector as consultants within multidisciplinary teams.

Current contact with autistic patients

A quarter of respondents reported having one or more autistic children under their care, with almost 70% reporting having one or more autistic adults under their care. A large proportion (86.6%) had been approached by at least one patient about a suspected autism diagnosis.

Training on autism

Just over two-thirds of respondents reported receiving specialist training about autism. This largely included diagnostic training and use of specific instruments, but some also reported intervention training such as Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. Just under a third of respondents reported receiving no autism-specific training at any stage.

Personal experience and knowledge of autism

Two respondents were autistic themselves, 12 had an autistic child, 36 an autistic relative, and 32 an autistic friend or colleague. The mean score of correct answers on the Knowledge of Autism Scale was 91.2% (range 31.8-100%). The score was significantly higher for those who identified as having personal experience of autism than those without.

Diagnostic processes and pathways

Over three quarters of the 111 respondents involved in diagnosing patients reported waiting times of over 3 months. The majority (69.1%) reported experiencing situations whereby a patient did not meet formal diagnostic criteria, but their clinical judgement suggested otherwise. A third of these still gave the diagnosis in these situations, while others gave alternative diagnoses, used alternative tools, or referred patients on to specialists. The protocol for diagnosis was mostly standardised (78.4%), commonly incorporating a combination of diagnostic instruments, clinical judgement, clinical observations, parent report, and DSM/ICD diagnostic criteria.

Self-efficacy

The reported confidence of respondents varied widely. Higher self-efficacy scores were significantly related to better knowledge of autism scores and the total number of autistic patients under their care. Self-efficacy scores were also significantly higher for those psychiatrists who had received training on autism compared to those who had not.

Qualitative analysis of open-ended responses

Thematic analysis yielded seven themes describing systemic and autism-specific challenges to delivering effective care and support:

- Lengthy waiting lists mean a lack of timely support

- Demand outstrips existing, chronically under-resourced services and support

- Lack of clarity around diagnostic and support pathways, including a lack of cross-agency working

- ‘Commissioning gap’ for services for autistic adults without mental health issues or intellectual disability

- Severely limited post-diagnostic support and services for patients and patients’ families

- Need for better understanding of autism, including for professionals beyond psychiatry

- Tensions regarding the position of autism in society.

Just under a third of psychiatrists who responded to the online survey reported receiving no autism-specific training at any stage.

Conclusions

The authors confirm that a large majority of psychiatrists will be responsible for or have input into the care of autistic individuals. They generally acknowledged that the number of autistic individuals in their care or requesting diagnostic assessments is increasing. Most had received specific training on autism, and they had a high level of knowledge about autism generally, particularly if they had personal experience of autism. Higher levels of self-efficacy were related to greater knowledge, experience and training in autism. However, although they reported the work with autistic people as interesting and rewarding, the psychiatrists in this study highlighted several important systemic or autism-specific factors that presented as a challenge to providing the most effective care and support.

Several important systemic or autism-specific factors presented as a challenge to providing effective care and support.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides an important analysis of the current state of psychiatrists’ knowledge, experiences and challenges in identifying and supporting autistic individuals. This study is the first to survey a large number of psychiatrists about their experiences, confidence and beliefs about autism in their patients in detail. It uses a nice balance of questionnaire measures and qualitative data collection and subsequent thematic analysis.

There is a typical concern that those clinicians who responded to the survey effectively self-selected and may therefore not represent the national picture of autism knowledge and training among psychiatrists in the UK. There is potentially an underrepresentation of eating disorder consultants (1.7%), given that it is known that many patients with eating disorders are also autistic (Huke et al., 2013).

One potential limitation of the methods is that the data has not been broken down by the demographics of the respondents. For example, it would be interesting to know differences in findings for those psychiatrists working on hospital wards (25%) compared to those in community mental health teams (50%) for example. Additionally, it would be interesting to compare results for individuals working with autistic children and adolescents compared to autistic adults, especially in terms of ease of diagnosis and the service provision for these groups.

This study is an important analysis of the current state of psychiatrists’ knowledge, experiences, and challenges in supporting autistic individuals.

Implications for practice

Although the study highlights high rates of training on autism for psychiatrists, not all respondents had been adequately trained (only two thirds) and this should perhaps be mandatory given the high rates of autistic individuals presenting as patients to this group of clinicians. Further, a quarter of those who had received training reported it to be low in usefulness, suggesting that training needs to be designed carefully to meet the clinicians’ and patients’ needs.

The protocol for making a diagnosis seems to vary widely. Nationally, we need to work on how we diagnose autism in children and adults to optimise this process for the individuals concerned.

Lastly, the qualitative analysis made it very clear that service provision is severely lacking for autistic individuals. As an autistic woman in my 20s, I can confirm that this is indeed true. In our increasingly neurodiverse society, we need to better address support services for all individuals with autism and their families.

In our increasingly neurodiverse society, we need to better address support services for all individuals with autism.

Conflicts of interest

E.S. reports no conflicts of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Crane, L., Davidson, I., Prosser, R., & Pellicano, E. (2019). Understanding psychiatrists’ knowledge, attitudes and experiences in identifying and supporting their patients on the autism spectrum: online survey. BJPsych Open, 5 (3), e33.

Other references

Autism and mental health A guide to looking after your mind (PDF). Autistica.

Huke, V., Turk, J., Saeidi, S., Kent, A., & Morgan, J. F. (2013). Autism Spectrum Disorders in Eating Disorder Populations: A Systematic Review. European Eating Disorders Review, 21 (5), 345-351.

Photo credits

- Photo by Michał Parzuchowski on Unsplash

It is great that a understanding of autism is prevalent across psychiatric practice, as working with those with autism presents both a unique privilege and sometimes some challenge.

The obvious concern is about specialist training, which may not be accessible in all cases due to training dichotomies and current case bearing. It would be reasonable to suggest that the curriculum include, during training, some dedicated exposure to assessing and working with those with autism.

“There is a typical concern that those clinicians who responded to the survey effectively self-selected” – did wonder about this; interestingly 12/173 (so, what, about 7%?) of the respondents have a child with autism, which – bearing in mind that some respondents will have no kids – seems perhaps a bit higher than you’d expect from the general population (or, possibly, my stats is bad). Which *might* hint that the respondents were more likely than the general population to have direct experience of autism.

Bit speculative, I realise.