The usefulness of diagnostic labels has been much debated over recent years. They can save lives, but also destroy them (Watts, 2018); with comprehensive arguments presented by differing voices (e.g. Bril-Barniv et al., 2016; Johnstone et al 2018; Maj, 2018).

In response to this, research programmes in the USA are attempting to provide alternative frameworks for categorising mental health needs (Insel et al 2017; Kotov et al 2017). Some key considerations are the:

- Need to recognise and understand the perspectives of people being given a diagnosis and the stigma often attached to this (Hemming, 2018; Huggett et al., 2018; Sheffer et al., 2014).

- Challenges for those diagnosing; such as the risk and implications of misdiagnosis (Alsaif, 2016), as well as variations in diagnostic criteria (Barbano et al., 2018).

A new review published in The Lancet Psychiatry aimed to “understand and inform diagnostic practice through a comprehensive synthesis of qualitative data on views and experiences from key stakeholders (service users, clinicians, carers, and family)” (Perkins et al, 2018).

This is the first mental health systematic review to synthesise data on the entire diagnostic process and include the views of carers and family.

Methods

This study was a systematic review of published literature based on qualitative research (PsychINFO, MEDLINE CINAHL; October 2016-July 2017), as well as other publications to counter potential publication bias. The aim was to understand the factors that influence service user experiences of the diagnostic process, and to make this accessible to all.

- Inclusion criteria covered primary research with a ‘formal’ qualitative component, translated where necessary, collecting data from service users, carers, family or clinicians (or a mix of these groups) regarding the process of adult mental health diagnosis

- Exclusion criteria were developmental disorders, somatoform disorders, substance use and dual-diagnosis, dementia, traumatic brain injury and diagnosis under age of 18

- A service user, a clinician and academics contributed to the analysis. The authors found 18,104 relevant records, 11,039 abstracts or titles were assessed, and 533 full-text articles were screened for eligibility

- 67 studies from 13 countries were carried forward for thematic analysis:

- 31 involved service user participants, 15 clinicians, 7 carers, and 8 were mixed

- 51 were from the UK, USA and Australia.

- 79% of studies focused on psychosis, depression, personality disorders or mixed diagnoses

- Settings were inpatient, specialist, primary care, and community services.

Results

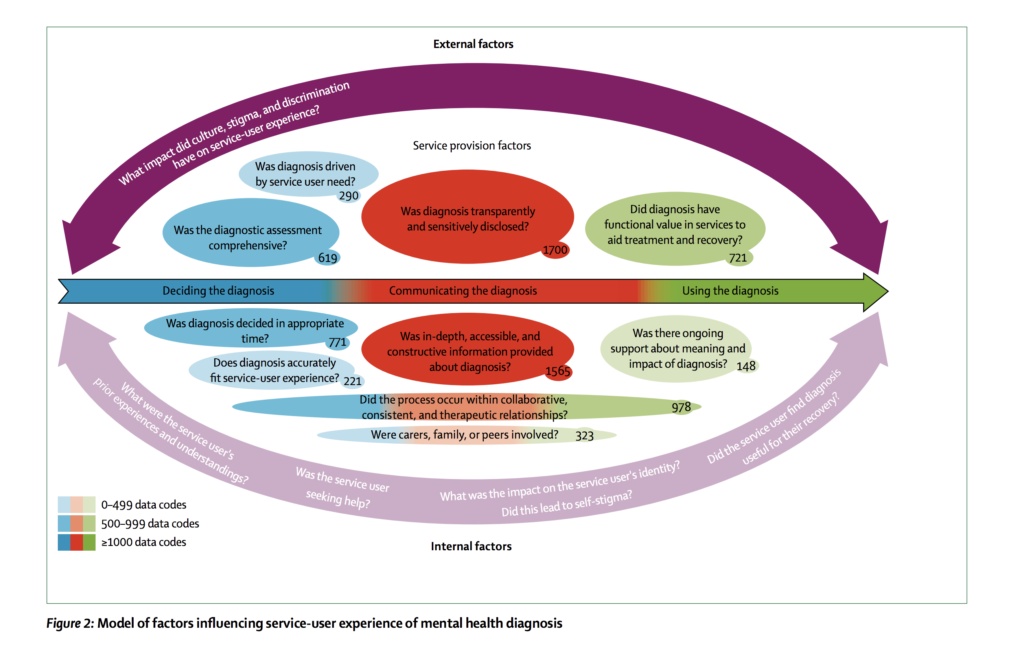

There is a lot of information to digest in this review; we have picked out a few areas to summarise, but we urge you to read the full text if you can to digest in detail. Three themes emerged as key influences on experiences of diagnosis: Service provision; external factors; internal factors. There is an interaction between these in that “the external and internal factors predate, occur alongside, and postdate service-level influences”, suggesting to us that service provision factors are the overarching focus of this paper.

- Service provision factors (the most highly reported theme) provided the immediate context for the diagnostic process in three stages:

- Deciding the diagnosis (drivers of diagnosis, quality of assessment, time taken to diagnose, accuracy and fit of diagnosis)

- Communicating the diagnosis (disclosure, provision of information)

- Using the diagnosis (functional value of a diagnosis, ongoing support)

In addition the authors highlighted two further service provision factors that impacted across the stages: collaborative and therapeutic relationships; and the involvement of family, carers and peers.

- External factors

- Impacts of culture, stigma and discrimination

- Support from others (including trained and supported peer workers)

- Internal factors

- Service users’ previous experiences of diagnosis and help-seeking

- Service user identity and ‘recovery’

These three themes are presented as a model (see below). The journey through service provision stages was mostly sequential but the circularity of diagnosis experiences was also noted. The authors found the factors having most influence on service user experiences of diagnosis related to communication, including whether the diagnosis was disclosed transparently and sensitively, with accessible and useful information provided.

Model of factors influencing service-user experience of mental health diagnosis. Click image to view full size.

The authors consider each theme in turn and describe the views of clinicians and service users. They consistently provide a balance between these two perspectives, although the views of carers and family members were largely absent. Substantial variation in experiences were highlighted for ‘service user identity and recovery’. Other variations included personality disorder diagnosis which was found to have the least functional value and most likely to lead to a deprivation of services. Depression was most commonly experienced as validating but difficult to diagnose and most readily understood within a medical model; psychotic diagnoses were least likely to involve adequate involvement of family members.

A consistent observation in the data was uncertainty in the diagnostic process, and the potential incompatibility of service user and clinician needs around this. For example:

service users often felt diagnosis was delayed, causing uncertainty, sense of rejection or abandonment, and delay in treatment. Service users more often reported a positive experience when diagnosis was felt to be efficient and timely.

Contrastingly, clinicians:

expressed that diagnosis is complex; a comprehensive assessment takes time… there was uncertainty about deciding when they crossed the threshold into something diagnosable and complications from symptom fluctuation.

Further to the above, clinicians feared over-labelling and causing harm (to the extent of clinicians opting for euphemisms), versus service user reporting of negative experiences where diagnosis is withheld. Uncertainty seemed part of the diagnostic process; how it was dealt with was felt to be crucial and linked to the importance of therapeutic relationships, strong communication, and collaborative processes; although these were infrequently reported.

We felt the issue of time and timeliness is particularly important, running through all stages of the diagnostic process. What is clear from the review is the recurrence of service user and clinician anxiety, stigma and power dynamics.

“Many clinicians reported reluctance to disclose due to fear of subjecting service users to stigma or damaging the therapeutic relationship, yet non-disclosure was more often associated with these outcomes”.

Conclusions

The use of diagnostic manuals and the clinician-service user divide creates a power imbalance that is no longer helpful. We agree with the authors’ recommendations around collaborative diagnostic decision making, and the central importance of open dialogue to improve service user experiences. The model provides a ‘holistic approach’ encompassing biopsychosocial factors. It also recognises individual variation in experiences of the diagnostic process; what is empowering for some is destructive for others. There are many practical points raised in the discussion to improve service user experiences, in summary:

- Address individual needs and expectations of diagnosis between service users and clinicians through collaborative discussion;

- Be aware of different influences on experiences of diagnosis including culture, as well as financial in countries such as USA and Australia;

- Access to information is vital. Draw upon peer support and service user communities as resources to support the process of diagnosis;

- Develop diagnostic processes that are digestible and meaningful;

- Consider adopting a case-formulation approach to diagnosis integrating principles of psychological formulation;

- Time is important not just in the process of diagnosing but across all staff-service user interactions.

“Our synthesis identifies that how diagnoses are decided, communicated and used by services is important. Disclosure, information provision, collaboration, timing and functional value for recovery were the most prominent themes”.

Strengths and limitations

We found this paper was very well written, with an appropriate methodological approach applied. This subject, the diagnostic process, however is a hotly contested area. The authors acknowledge this, but it would have been useful for them to have acknowledged their own positionality in two regards:

- Although the team included a service user and clinician, we would like to see more emphasis and clarification on how this expertise was used in the co-design and co-production process

- The authors do not outline their own views on diagnosis.

The review authors drew upon a good range of literature, and cited directly from the reviewed papers as well as providing their own meta-synthesis. Some of the data panels were confusing with direct quotes from papers alongside citing ‘interpretations of study authors’ with unclear links, which lost us at times.

As the authors note, the range of diagnosis included was limited by lack of literature meeting the study criteria, nonetheless does give a thorough overview of those covered.

Dual diagnosis was excluded, however co-morbid substance abuse should not be overlooked, being also included as possible criteria for some diagnoses. A wider range of diagnoses, therefore, may add value to this work.

The lower levels of involvement of friends, family and carers in research and importance of informal support would benefit from more discussion, and may be an opportunity for further research.

Although culture is lightly discussed, this would benefit from more depth analysis, and another missing element is language and literacy which can be barriers to understanding a diagnosis, as well as limiting service provision. With this in mind, the usefulness of a diagnosis must be contextualised, in particular when talking about choice, access to services and how ‘recovery’ is perceived (Slade et al., 2014).

The authors of this excellent systematic review do not outline their own views on diagnosis, which is a shame.

Implications for practice

There are clear benefits for practice, if recommendations from the review including collaborative decision making can be followed. However, more work is needed in different countries to understand whether and how in practice this can be delivered, and better outcomes achieved. The review and model development is only a first step.

Conflicts of interest

We do not have any direct conflicts of interest to declare but welcome this review and its contribution to research and pubic discussions on the role of diagnosis in managing emotional distress and long term mental ill health. We called on the authors to be transparent about their views on diagnosis. Our own are as follows:

Jennie Parker: My experience of diagnosis is a lengthy one, ranging from depression “treated” with pharmacology, CBT, ECT, and finally to my current and more fitting diagnosis. This diagnosis came as a huge relief in understanding why previous treatments had not helped. Once I was given information to ‘self-research’ (a term the authors use), this facilitated pursuing and holding responsibility for self-development, eventually leading to a career change to a role where I am able to be open about my experiences and use this in co-production of both research and service delivery. It was a difficult journey, based on low expectations, but my persistence has led to finally finding the right support. Whether I would have got to this point without a mental health label is difficult to know; however this label is also one that prohibited access to many services.

Vanessa Pinfold: I try to be open minded about diagnosis as the peer researchers I work with talk about both the positives and negatives of a ‘label’ that on the one hand provides access to treatment, personal understanding and peer support but on the other can restrict all of these and attract stigma as well as discrimination. Similarly, practitioners talk about the limitations of the diagnostic model and its flaws, whilst recognising its (growing) importance allocating resources through the benefits systems, courts, and schools.

We agree with the authors’ recommendations around collaborative diagnostic decision making, and the central importance of open dialogue to improve service user experiences.

Links

Primary paper

Perkins A, Ridler J, Browes D, Peryer G, Notley C, Hackmann C. (2018) Experiencing mental health diagnosis: a systematic review of service user, clinician, and carer perspectives across clinical settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Apr 18. pii: S2215-0366(18)30095-6. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30095-6. [Epub ahead of print]

Other references

Barbano, A. C., van der Mei, W. F., Bryant, R. A., D. L. Delahanty, deRoon-Cassini, T. A., Matsuoka, Y. J., Olff, M., Qi, W., Ratanatharathorn, A., Schnyder, U., Seedat, S., Kessler, R. C., Koenen, K., C., & Shalev, A. Y. (2018). Clinical implications of the proposed ICD-11 PTSD diagnostic criteria. Psychological Medicine 1–8. [PubMed abstract]

Bril-Barniv, S., Moran, G. S., Naaman, A., Roe, D., & Karnieli-Miller, O. (2017). A qualitative study examining experiences and dilemmas in concealment and disclosure of people living with serious mental illness. Qualitative Health Research, 27, 573–83.

Huggett, C., Birtel, M. D., Awenat, Y. F, Fleming, P., Wilkes, S., Williams., S, & Haddock, G. (2018). A qualitative study: experiences of stigma by people with mental health problems. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice – British Journal of Psychology, https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12167 [PubMed abstract]

Insel, T., Cuthbert, B., Garvey, M., Heissen, R., Pine, D. S., Quinn, K., Sanislow, C., & Wang, P. (2010). Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167, 748-751.

Kotov, R., Krueger, R. F., Watson, D., Achenbach, T. M., Althoff, R. R., Bagby, R. M., Zimmerman, M. (2017). The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP): A dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies (PDF). Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126, 454-477.

Johnstone L, Boyle M, with Cromby J, Dillon J, Harper D, Kinderman P, Longden E, Pilgrim D, Read J. (2018) The Power Threat Meaning Framework: Towards the identification of patterns in emotional distress, unusual experiences and troubled or troubling behaviour, as an alternative to functional psychiatric diagnosis (PDF). Leicester: British Psychological Society.

Maj., M. (2018). Why the clinical utility of diagnostic categories in psychiatry is intrinsically limited and how we can use new approaches to complement them. World Psychiatry 17(2).

Sheffer, G., Cross, S., Howard, L., Murray, J., Thrnicroft, G., Henderson, C. (2014). Diagnostic Overshadowing and Other Challenges Involved in the Diagnostic Process of Patients with Mental Illness Who Present in Emergency Departments with Physical Symptoms – A Qualitative Study. PLoS ONE 9(11): e111682. doi:10.1371/.

Slade, M., Amering, M., Farkas, M., Hamilton, B., O’Hagan, M., Panther, G., Perkins, R., Shepherd, G., Tse, S., & Whitley, R. (2014). Uses and abuses of recovery: Implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 12–20.

Watts, J (2018) Mental health labels can help save people’s lives. But they can also destroy them. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/24/mental-health-labels-diagnosis-study-psychiatrists (Accessed 21/5/2018)

Photo credits

- Photo by Ahmed zayan on Unsplash

- Photo by Easton Oliver on Unsplash

- Photo by rawpixel on Unsplash

- Photo by Kristina Flour on Unsplash

- By Stokkestijn [CC BY-SA 4.0], from Wikimedia Commons

[…] Mental health diagnosis: views and experiences of service users and clinicians […]

i worked on the stigma as regards work place,within the media and the press. we also worked on the stigma within sport and the armed services.this was funded by the government,on a six year time line.it was funded by many millions of pounds and was undertaken by the u.k. government and was named s.h i.f.t i worked within all the above topics. we came up with ways of tackleing the word s.t.i .g.m.a in mental health. martin rukin.