Modern lifestyle is directly affected by individual health behaviours, like diet, exercising, and medication adherence, and even small behavioural changes can significantly improve wellbeing. However, motivation remains an important factor that affects changes to health behaviour, and must be intrinsic in order for change to be sustainable and directly contribute towards wellbeing.

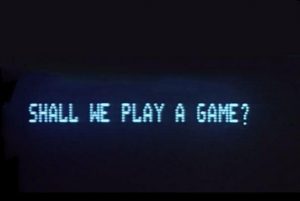

This is a challenge for the majority of modern interventions because they are not particularly motivating, let alone exciting. Therefore, it is time to introduce a new concept: gamification.

‘Gamification’ is a currently a hot topic in mental and physical health discussions, but what does it mean? In brief, gamification is the use of game design elements in non-game contexts (Deterding et al, 2011) and includes:

- Feedback,

- Goal-setting through interface elements like point scores, badges, levels or challenges, and

- Avatars.

Depending on whom you ask, the number of game elements varies from 6 to over 30, and the relative importance of these elements also varies. However, the main aim of using game design elements is to increase engagement and motivation. The concept of health gamification first appeared in 2010 and examples of successful gamification applications include ‘Nike+’ (an activity tracker) and ‘Zombies, Run!’ (this app motivates you to run while escaping a zombie apocalypse).

Gamifying physical exercise: the ‘Zombies, Run!’ app motivates you to run while escaping a zombie apocalypse.

This blog looks at a literature review by Johnson et al (2016) that examined the effectiveness of gamified applications for both health and wellbeing. In their research the authors investigated:

- What evidence is there for the effectiveness of gamification applied to health and wellbeing?

- How is gamification being applied to health and wellbeing applications? What specific game elements, delivery platforms and theories of motivation are being used?

- What audiences are targeted? What effects between different audiences are observed?

- What health and wellbeing domains are targeted?

Methods

Overall, nine databases were searched, including manual searches through the reference lists of key studies. Authors used prior systematic reviews on gamification and health and wellbeing to help build search strategies. Authors identified eight inclusion criteria, to include high-quality work reporting original research. To avoid duplication, earlier versions of studies fully reported later were excluded.

Authors used quality assessment methods presented by Connolly et al (2012). The tool is used to assess the overall weight of empirical evidence for the positive impact and outcomes of games.

The authors used design game categorisation based on that used by Hamari et al (2014), which included: Avatars, Challenges, Feedback, Leader-boards, Levels, Progress, Rewards, Social interaction and the Story or Theme.

The section on measuring and categorising the ‘effects’ is rather messy. The authors categorised ‘health’ and ‘wellbeing’ effects as relating to affect, behaviour, and cognition. In addition, the ‘effects’ investigated were positive, negative, or mixed/neutral. User experience was also reported, which the authors defined as ‘an attitude towards a gamified intervention.’

Gamification has become very prevalent especially in the fitness world, with many devices and apps now available.

Results

The literature search identified 365 papers, and 19 articles were included in the review.

Out of the 19 studies, 3 papers (16%) were categorised as providing moderate evidence and 8 papers (42%) were categorised as providing strong evidence. More than half of the included studies (n = 10) did not compare gamified and non-gamified versions of the interventions studied. Sample sizes varied dramatically from 5 to 251.

Most interventions were delivered through websites or mobile apps, and sometimes used a combination of both. The most commonly employed game design elements were rewards, leader boards and avatars.

Overall, the positive effects of gamified interventions were reported in the majority of cases (n = 22; 59%), with a significant proportion of neutral or mixed effects (n = 15; 41%). No purely negative effects were reported.

More positive outcomes were found for children and young adults rather than adults. The majority of assessed outcomes were behavioural or cognitive, while affect was rarely reported.

Only 12 studies measured user experience, and the majority of respondents in these studies reported positive or mixed results.

The authors cautiously suggest that their review shows that gamification can have a positive impact on health and wellbeing, particularly for health behaviours.

Discussion

The authors concluded that:

Gamification has been well received; it has been shown to foster positive impacts on affect, behaviour, cognition and user experience.

Negative effects can be explained by inadequate designs of the gamified interventions and their delivery. The authors concluded further that gamification research is a fast-developing field; however, the quality of evidence is still below the desirable level.

These results suggest that the gamification of health and wellbeing interventions can lead to positive impacts, particularly for behaviours in the physical health domain, however the situation is less clear for cognition and affect. Most importantly, the authors noted that user experience can be crucial in successful implementation and shouldn’t be ignored.

It is important to note that not a single included study investigated the effects of game design elements on intrinsic motivation as a direct outcome.

None of the included studies investigated the effects of game design elements on intrinsic motivation as a direct outcome.

Strengths and limitations

This work provides a valuable insight into the current research on gamification. Indeed, up until this systematic review, there had been no attempt to assess the quality of the existing studies that examined gamified interventions and their effect on health.

One of the strengths and, paradoxically, limitations of this systematic review is its attempt to embrace everything within the field of gamification, and instead of focusing on a couple of outcomes, the authors decided to investigate everything related to this concept. Subsequently, we have a comprehensive review that summarises the current evidence, but there are certain points to consider.

Firstly, it is worth asking about the clarity of definitions in this systematic review. While the meaning of gamification was clear to me, as a reader, I remained unconvinced by the definitions of “wellbeing” and “health” used by the authors. Both concepts are rather broad and require more in-depth explanation than just one sentence from a 1946 report by the World Health Organization.

An unclear definition of the key components of the research questions leads to the next problem with defining the effects of health and wellbeing; behaviour, cognition and affect. The authors have chosen to use a three-component model of attitudes which has not been justified. Therefore there is a possibility that some of the other effects of gamification on health and wellbeing were missed.

Secondly, the choice of quality assessment tool should be considered. If you carefully read the initial paper by Connolly et al (2012), you will notice that there is not much explanation on what denotes ‘low’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high’ quality. Therefore, while it’s a solid attempt to assess the quality of the papers, this particular tool raises queries with regard to its validity.

Conclusion

The growing interest in gamified interventions to improve mental and physical health has resulted in the evidence base growing at a sonic speed. Although, there is a strong need for well-designed studies and more RCTs, the current evidence suggests very encouraging results, in particular for physical health. There is still a lack of adequate definitions in this field, but I think it is only a matter of years until a consensus will be reached.

More well-designed studies are needed in this field, but gamification is a promising new technique that we are likely to hear much more about over the coming years.

Links

Primary paper

Johnson D, Deterding S, Kuhn K, Staneva A, Stoyanov S, Hides L. (2016) Gamification for health and well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Internet Interventions 6 (2016) 89–106 [Accepted manuscript PDF]

Other references

Stevens, G, Mascarenhas M, Mathers C. (2009) Global health risks: progress and challenges. Bull. World Health Organ. 87(9) 646. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.09.070565

Deterding S. et al (2011) Situated motivational affordances of game elements: a conceptual model (PDF). Gamification: Using Game Design Elements in Non-gaming Contexts, a Workshop at CHI.

Connolly TM, Boyle EA, MacArthur E, Hainey T, Boyle JM. (2012) A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Comput. Educ. 59(2) 661–686. [Abstract].

Hamari J, Koivisto J, Sarsa H. (2014b) Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences:pp. 3025–3034. [Abstract]

[…] Read the full research overview here […]

Thanks for a thought-provoking post!

The length of follow-up in these studies is really important. I’d guess it would probably take a little while for gamification to crowd-out intrinsic motivation. We also need to know what happens once the gamification is taken away – are we assuming that it’ll be available indefinitely? We need to seriously think about the potential for dependency and which aspects of gamification might reinforce that.

Shout out for my personal favourite bit of health-improving gamification, to which I am 100% addicted and dependent: Fetchpoint http://www.fetcheveryone.com/game-fetchpoint.php

Dear Sasha

Could you please provide me with your e-mail address so that we could discuss an area of possible interest