The woodland has several blogs in relation to ‘treatment resistant depression’ looking at a range of topics from the patient experience to the cost effectiveness of interventions such as long term psychoanalytic psychotherapy.

I put treatment resistant depression (TRD) in italics above as you may be surprised to know that there is no consensus on its definition, which in turn means that the incidence rates vary and there are no consistent clinical guidelines in relation to treatment (Gabriel et al 2023).

The US Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency have adopted the most used definition of TRD (inadequate response to a minimum of two antidepressants despite adequacy of the treatment trial and adherence to treatment). It is currently estimated that at least 30% of persons with depression meet this definition and so the burden of this aspect of depression is not insignificant (McIntyre R et al 2023).

The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines (Taylor et al 2021) first choice options for management of TRD include augmentation with lithium and quetiapine. This blog looks at the new randomised controlled trial by Prof Tony Cleare et al, published today in The Lancet Psychiatry, directly comparing the clinical and cost effectiveness of the two. This paper is particularly interesting as the trial (the LQD study (Lithium versus Quetiapine in Depression)) has a much longer follow up period than previous studies, enabling a ‘real life’ comparison.

The LQD study, published today in the Lancet Psychiatry compares the clinical and cost effectiveness of lithium and quetiapine for treatment resistant depression.

Methods

So, this trial is a *takes a deep breath* “phase 4, pragmatic, open label, parallel-group, randomised controlled superiority trial, comparing the clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of lithium versus quetiapine augmentation of antidepressant medication in participants with treatment-resistant depression.”. Let me break that down for you:

- Phase 4: medication is approved and being used in practice. These trials look at long term safety and effectiveness in practice

- Pragmatic: looking at the effectiveness of medications in real life situations

- Open label: participants and researchers know which treatment the participants are receiving (non-blinded study)

- Parallel group: two active treatment groups, which are then compared

- Randomised controlled superiority trial: participants were randomly assigned to treatment groups and reviewed as to which treatment performs better.

Clinical effectiveness process: Following random allocation to treatment, trial clinicians could decide whether to proceed with prescription of the allocated medication based on pre-prescribing safety checks and clinical judgement. All participants, regardless of trial medication status, were followed up over 12 months unless they actively withdrew.

The primary outcomes were:

- The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS-SR) , used as a weekly measure of mood state and

- Time to discontinuation of treatment.

Weekly data on QIDS-SR, Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS) and trial medication status were collected via an online platform, True Colours.

Cost effectiveness process: The Client Service Receipt Inventory was used at baseline, 8, 26, and 52 weeks. This tool collects data on health-care service use, including the number and duration of contacts with primary and secondary health-care services. Quality-Adjusted Life Years (QALYs) were used to measure health benefits.

Results

Over a 4.5 year period (Dec 2016 to July 2021) 262 patients were screened for eligibility from 6 NHS Trusts across England. The inclusion criteria included:

- ≥ 18 years

- Under the care of a GP or mental health service

- Current depressive episode meeting DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder (single or recurrent episode)

- Score of ≥ 14 on the 17 item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

- Inadequate response of the current episode to two or more antidepressants, prescribed for at least 6 weeks at therapeutic dose

- Current antidepressant treatment unchanged and at therapeutic dose for at least 6 weeks; and

- Were able to provide written informed consent

Exclusion criteria included (but not limited to)

- Diagnosis of bipolar disorder or current psychosis

- Adequate use of lithium or quetiapine in their current episode

- Current use of another atypical antipsychotic.

There were primary, secondary and tertiary outcomes in the study. For this blog I will focus on the primary outcomes and note any key results from the secondary outcomes (tertiary outcomes were not included in this publication).

212 patients were randomly assigned:

- 105 assigned to lithium; 21 did not receive or initiate lithium but remained in the trial. 66 provided data at 52 week follow up

- 107 assigned to quetiapine; 12 did not receive quetiapine but remained in the trial. 78 provided data at 52 week follow up

Clinical effectiveness results

Primary outcomes

- Overall burden of depressive symptom severity over 12 months

- Time to all cause discontinuation

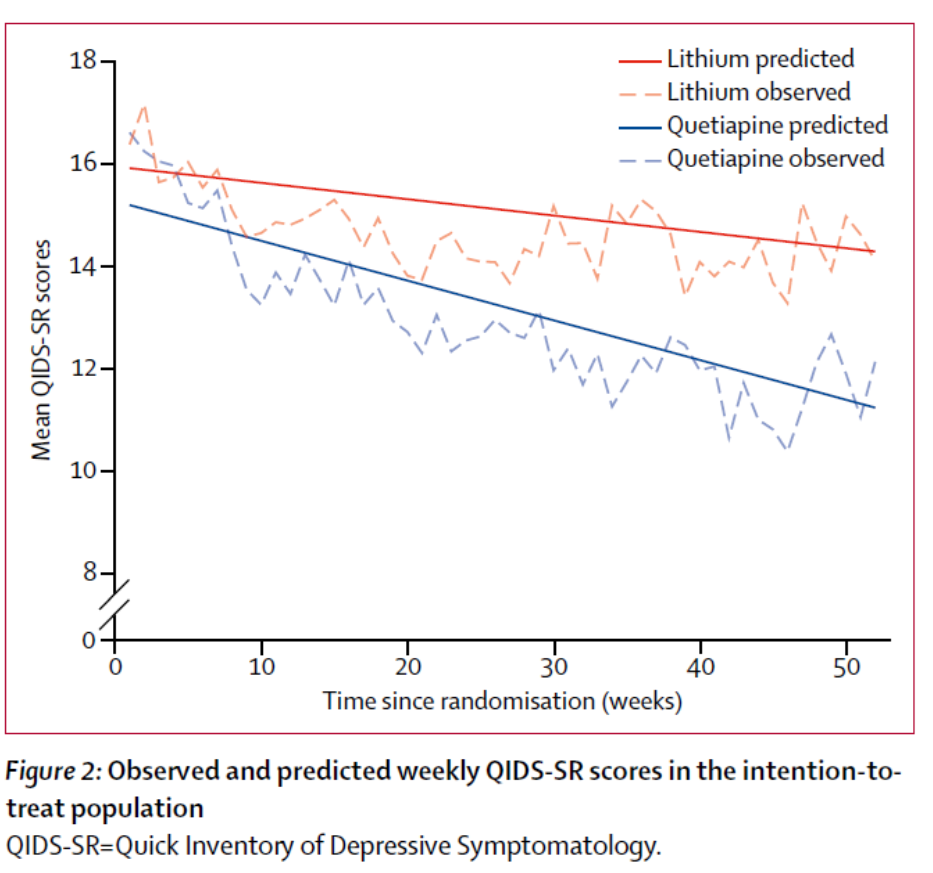

Participants in the quetiapine group had a lower overall burden of depressive symptom severity than participants in the lithium group over 12 months. The QIDS-SR data points were mapped over the year and the area under the curve calculation used as a measure of depressive symptom burden. The area under the curve was smaller for Quetiapine: (area under the difference curve –68.36 [95% CI –129.95 to –6.76]; p=0.0296).

Time to trial medication discontinuation did not differ significantly between the two groups; the median time was:

- 365.0 days (Inter-Quartile Range, IQR 57.0 to 365.0) in the quetiapine group

- 212.0 days (21.0 to 365.0) in the lithium group

- Adjusted hazard ratio [HR] 0.72 [95% CI 0.47 to 1.09]; p=0.1196.

Given the wide IQR and large discrepancy between the respective medians, we must consider this “absence of evidence” rather than “evidence of absence”.

In terms of secondary outcomes, participants in the quetiapine group had significantly lower MADRS (p=0.0435) and WSAS scores (p=0.0071) at week 52 than participants in the lithium group. No significant differences were noted in the other secondary outcomes which included physical health parameters and adverse events (see paper for full details). An interesting negative result was that no weight gain was observed across time in the quetiapine group.

Cost effectiveness results

Compared with lithium, quetiapine was dominant. Costs were lower while benefits were higher.

From an NHS and personal social services perspective, quetiapine was associated with lower cost and larger gain in QALYs, than lithium. The incremental net health benefit of Quetiapine was 0.097 over lithium (with any positive result indicating preference to the compared alternative). Additional cost effectiveness analysis are available in the appendices of the paper which outline that quetiapine is the most cost-effective option according to the NICE willingness-to-pay threshold.

The quetiapine treatment group had a lower overall burden of depressive symptomatology than lithium.

Conclusions

The authors concluded that:

our findings suggest a moderate and clinically relevant benefit of quetiapine over lithium for long-term treatment of participants with treatment-resistant depression.

And this study:

…extends the previous finding that quetiapine is non-inferior to lithium over the short term and suggest superiority over the longer term.

Compared to lithium, quetiapine is the most cost-effective option in relation to the NICE willingness-to-pay threshold.

Strengths and limitations

This paper has some real strengths in that its main aim was to mimic real-life clinical decisions and patients. There was lived experience involvement in designing and running the trial and patient and public involvement members were supportive of the weekly QIDS-SR assessments to provide a better indication of the course and long-term duration of outcome for what can be a fluctuating clinical course in treatment resistant depression (TRD). Following patients up for 1 year was a big plus.

Due to the nature of the trial, clinicians were not blind to allocation, however the authors report that ‘clinician rated outcome measures were assessed by masked raters and statisticians were unaware of group allocation until the data analysis phase’ to try and reduce bias as much as possible.

With every trial there will be limitations and this paper is no exception. Having clinician judgement as to whether the allocated medicine is prescribed potentially introduces allocation bias.

The patient groups were randomised according to degree of treatment resistance (failure of two versus three or more antidepressant treatments in the current episode) and they used ‘block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes’, however within the results there is no reference as to how many were in each group or whether the results correlated to this.

Most of the data relied on self-reports. Although this method was developed in partnership with patient groups, the burden may have contributed to attrition.

During the trial, the sample size was reduced from 276 to 214 due to challenges with recruitment. Power calculations were completed and were 80% for time to discontinuation and 96.5% power with an effect size of 0.38. It is however unclear if the discontinuation rates, effect sizes and attrition rates were changed from the original planning when calculating these. There appeared to be potentially concerning gaps in the 52 week collection data, more so for lithium (37% for the lithium group and 27% for the Quetiapine group) and the authors note substantial missing data for some of the secondary outcomes.

Overall, there was a lot of attrition, which should caution our interpretation of these results. The intention to treat analysis only included 66/104 and 78/107 of the lithium and quetiapine patients respectively. The different levels of attrition in each group may mean that we’re no longer comparing like with like across the groups.

Finally, the population examined was predominantly white (89%) which will limit the ability for generalisation to all populations.

Mimicking real life clinical practice over a year comes with it’s own limitations.

Implications for practice

Patients who have depression which is ‘difficult to treat’ are ‘clinically challenging’ and suffer a significant burden from the disease. Both lithium and quetiapine are common options for augmentation and this paper highlights that quetiapine may actually be more efficacious and cost effective than lithium. The length of follow up of the study makes this encouraging and certainly worth considering. The power of the study and the rather heterogeneous group of severity may limit leaping to an immediate use of quetiapine over lithium, but if there was future replication of this study and results, then that would certainly be convincing.

The authors are clear though that Lithium remains an effective treatment option. It is likely that the medications will have different benefits for different people (e.g. concerns in relation to sleep, appetite, anxiety) and so treatment should be tailored to these needs. However, if lithium and quetiapine are equally acceptable then quetiapine may just pip lithium to the post.

Having clear clinical guidelines in relation to strategies for ‘difficult to treat’ depression and/or when it becomes ‘treatment resistant’, seems a priority so that future research can be comparing apples with apples.

At the time of writing this, there is a complicating factor in that there is a national shortage of modified release quetiapine and we are having to move patients onto immediate release Quetiapine which has a different side effect profile and may not produce results replicable to the study.

Quetiapine may pip lithium to the post if on an even field.

The personal impact of treatment resistant depression cannot be underestimated and I am sure they would agree with the words of Bon Jovi ‘I just want to live while I’m alive…it’s my life’.

Statement of interests

I have no conflict of interests to disclose

Links

Primary paper

Anthony J Cleare, Jess Kerr-Gaffney, Kimberley Goldsmith, Zohra Zenasni, Nahel Yaziji, Huajie Jin, Alessandro Colasanti, John R Geddes, David Kessler, R Hamish McAllister-Williams, Allan H Young, Alvaro Barrera, Lindsey Marwood, Rachael W Taylor, Helena Tee, and on behalf of he LQD Study Group. (2025) Clinical and cost-effectiveness of lithium versus quetiapine augmentation for treatment-resistant depression in England: a pragmatic, open-label, parallel-group, randomised controlled superiority trial. The Lancet Psychiatry 2025. DOI: 10.1016/S2215-0366(25)00028-8

Other references

Gabriel FC et al (2023) Guidelines’ recommendations for the treatment-resistant depression: A systematic review of their quality. PLoS ONE 18(2): e0281501.

McIntyre RS, et al (2023) Treatment-resistant depression: definition, prevalence, detection, management, and investigational interventions. World Psychiatry. (2023) 22, no. 3, 394–412.

Taylor, David M, et al. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. 14th ed., John Wiley & Sons, 2021 pg 318-319.

Photo credits

- Photo by Nathan Dumlao on Unsplash

- Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

- Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash

- Photo by Stephen Lelham on Unsplash