Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a lifelong condition characterised by significant difficulties in social communication and interaction. Furthermore, those diagnosed with ASD frequently demonstrate restricted and repetitive patterns of behaviours and differences in sensory processing (Martinez et al., 2024; Symons, 2021).

In recent decades, growing awareness has helped many individuals to recognise these behaviours and experiences in themselves and the individuals around them (Kiehl et al., 2024). This increasing awareness may explain why there has been a substantial increase in the rate of people diagnosed with ASD in the United Kingdom (Lorenz, 2022).

Research has suggested that an ASD diagnosis can have an impact on an individual’s identity, wellbeing, and access to support (Kiehl et al., 2024). However, different factors (e.g., feeling respected, being involved within the diagnostic process, and a consideration of gender differences) have been found to impact the experiences of those who are receiving an ASD diagnosis in adulthood (Sandell et al., 2013; Hull & Mandy, 2017).

Until recently, no synthesis of existing qualitative research on the experiences of adults diagnosed with ASD had been completed. This changed with the work of Kiehl et al. (2024), a team of researchers who set out to compile existing qualitative data in hope of creating a visual representation of an adult’s journey from pre- to post-ASD diagnosis.

This qualitative meta-synthesis aimed to better understand, explore, and synthesise the lived experiences of individuals diagnosed with autism in adulthood.

Methods

Research within this review explored “adult ([18+]) service-user experiences of the ASD diagnostic process”. The researchers used their search strategy to find research from PsycINFO, Embase, MEDLINE, and CINAHL .

Included research consisted of research papers, book chapters, dissertations, and doctoral theses that were published between 4th January 1999 and 3rd January 2022. Eligible research was required to include a formal qualitative component in their analysis. To maintain quality, all studies had to meet the first two criteria of the CASP scoring system. Those criteria being, “Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?” and “Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?” (Oxford Centre for Triple Value Healthcare, n.d). No further quality appraisal was conducted during this research. To include a range of lived experiences, those who self-identified as autistic (without a formal diagnosis) and those studies that did not report a specific method of diagnosis were considered eligible.

Reference lists from included research papers were hand-searched for further eligible research. Two reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts independently. The first 50 titles and abstracts were screened by a third reviewer. 94% agreement consensus was established.

Reoccurring themes were identified by thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, 2008). The Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREC) statement was referred to when reporting the qualitative synthesis.

Results

24 studies, published between 2001 and 2021, met the inclusion criteria. Most of the studies were conducted in either the United Kingdom, Australia, United States of America, or Sweden. Researchers utilised a range of different methodologies, including semi-structured interviews, other types of interviews, questionnaires, and analysis of website contents.

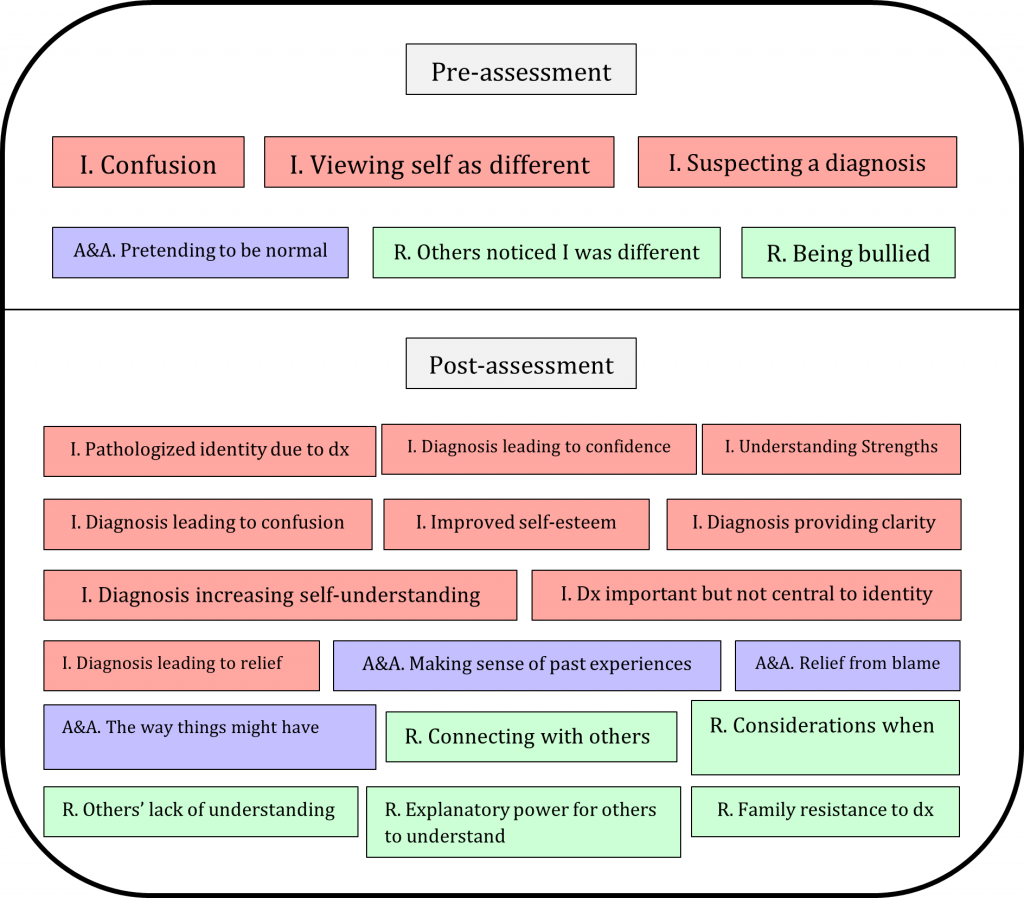

Kiehl et al. (2024) identified 32 descriptive themes from pre-to-post diagnosis. From these, three analytical (overarching) themes were identified: “impact on the self (Identity)”, “impact on people’s relationships (Relationships)”, and the role of “Adaption and Assimilation”. The third was created to represent the interaction between Identity and Relationships. See the findings in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The Descriptive themes that were identified from pre-to-post diagnostic assessment: Red or “I” = Identity; Purple or “A&A“ = Adaption and Assimilation; and Green or “R” = Relationship.

Pre-diagnosis:

“Identity” was the largest overarching theme that was identified by the researchers. Regarding this, many individuals described feelings of confusion and difference to other people. The researchers found that the reactions of other people (including peers, teachers, and family) and the autistic person’s experiences of bullying (due to being themselves) reinforced the feelings described above. Due to this, some individuals appeared to adapt their behaviours to “pretend” and “mask” the differences that they presented. This was found to be particularly prominent in a sub-analysis conducted into female-specific experiences. Females reportedly shared that their difficulties were often missed or mislabeled as another condition (e.g., depression, anxiety, personality disorders, or eating disorders). While experiencing feelings of “alienation”, participants of all gender identities were found to have identified and suspected similarities between the difficulties that they were experiencing and the descriptions of autism.

Post-diagnosis:

There was an overwhelming amount of data to suggest participants found diagnosis beneficial. Some described feelings of relief and clarity. Many experienced increased self-understanding, self-esteem, and confidence. A diagnosis allowed participants to make sense of past differences and difficulties and allowed participants a sense of relief from past blame. Although less prevalent, some described confusion, uncertainty, or devastation as their diagnosis “pathologized their individuality”. There was also an awareness of how an earlier diagnosis may have helped, with some mourning the lives they could have lived if they had received a diagnosis earlier in their life. In the female-specific sub-analysis, it was found that females often focused their grief on the future and lack of post-diagnostic support available to them.

The value of connection to other autistic individuals was a prominent and important theme that was identified following a diagnosis. Within this, an individual’s choices of disclosing their diagnosis to other people were guided by an individual’s desire for understanding, fear of stigma, consideration of consequences, and other people’s understanding. While diagnosis provided an explanatory framework for the participant’s personal experiences and behaviours, a lack of understanding led to a resistance of the formal diagnosis by other people (e.g., family members). In the female-specific sub-analysis, it was found that females found validation and acceptance in connecting with others.

This review found that overwhelmingly, a diagnosis of autism in adulthood was perceived to be beneficial and led to increased self-understanding, self-esteem and self-confidence.

Conclusions

Through their visual depiction, the researchers were able to convey that the diagnostic process for adults is a transformational journey that has a significant impact on the identity and relationships of those assessed. The stories of those who have journeyed through the diagnostic process should be used to shape future processes.

Rather than being a turning point moment, receiving a diagnosis of autism in adulthood appears to be a transformational journey.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths:

- Kiehl et al. (2024) demonstrated transparency by providing an example of the search strategy they used. This has provided future researchers with the opportunity to replicate and advance these findings in a reliable manner.

- Lived experience was considered throughout this study. Firstly, a researcher with lived experience of receiving an ASD diagnosis in adulthood was involved in the production of this research. Secondly, this study’s final framework was discussed with an advisory group of people with lived experience of receiving an ASD diagnosis in adulthood and two clinicians with experience of diagnosing adults with ASD. Due to this, the researchers were able to refine the language they used, the descriptions they provided, and how they framed their descriptive themes.

- 82% coding consensus was established between the three researchers. This is above the minimum level of acceptable inter-rater reliability (i.e., 80%) that was suggested by Saldaña (2009).

Limitations:

- The reviewers limited their search to just 3 years (4th January 1999 to 3rd January 2022), but still included 24 studies in their review, so it’s highly likely that there is significantly more research on this subject. As such, this paper should be viewed as a summary of a small proportion of the available evidence on this topic, rather than a systematic review.

- Kiehl et al. (2024) were transparent in that they synthesised de-contextualised data. The researchers suggested that there is a possibility that their themes may not reflect the meanings held within the original data.

- To reflect a range of lived experiences, the researchers accepted research that included participants without a formal diagnosis of ASD and those who did not report a specific method of diagnosis. However, this may call into question the validity of some of these studies’ findings, as a formal diagnostic tool may not have been used to officially diagnose an individual’s experiences as ASD. It is acknowledged that there are concerns within autism-related literature about the accessibility to diagnostic assessments, the utility of a diagnostic label, and the accuracy of the diagnostic process (Fellows, 2023). However, there are also concerns within the literature about the absence of research in this field and the validity of those who self-diagnose as autistic (e.g., those self-diagnosing may lack diagnostic training and the possibility of confirmation bias when examining one’s own behaviours) (McDonald, 2020; Sarrett, 2016).

It is important to acquire the opinions and perspectives of those at the centre of a research question. For Kiehl et al. (2024), this helped to reflect the real lived experiences of autistic people who have been through the diagnostic process themselves.

Implications for practice

This research suggests that the language used during diagnosis should aim to provide clarity and sensitivity and help individuals to process and reflect on their diagnosis. Diagnosticians and services should also consider the utility of shared decision-making and further patient-centred training to help support the development of diagnostic, clinical, and support services.

Kiehl et al. (2024) suggested that individuals be given multiple sessions with a clinician to process and reflect on what a diagnosis means for their identity, relationships, and interactions with others. This is especially important as research has found that self-acceptance and building relationships is important to those who receive a diagnosis of autism as an adult (Crompton et al., 2022).

It is suggested that a diagnostic process that initially considers these needs may promote acceptance and adaptation, reduce confusion, and reduce the need for immediate post-diagnostic support. This research suggests that post-diagnostic support should consider, and be informed by, the possibility that an individual may experience difficulties with identity, grief, and loss following a diagnosis.

Language is powerful! Diagnosticians should use shared language that encourages clarity, reflection, and sensitivity to one’s experiences.

Statement of interests

No formal conflicts of interest.

Links

Primary paper

Kiehl, I., Pease, R., & Hackmann, C. (2024). The adult experience of being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Autism, 28(5), 1060-1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/13623613231220

Other references

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101. – 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Crompton, C. J., Hallett, S., McAuliffe, C., Stanfield, A. C., & Fletcher-Watson, S. (2022). “A group of fellow travellers who understand”: Interviews with autistic people about post-diagnostic peer support in adulthood. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 831628. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.831628

Fellowes, S. (2024). Establishing the accuracy of self-diagnosis in psychiatry. Philosophical Psychology, 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2024.2327823

Hull, L., & Mandy, W. (2017). Protective effect or missed diagnosis? Females with autism spectrum disorder. Future Neurology, 12(3), 159-169. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl-2017-0006

Lorenz, S. (2022). Study of England and Northern Ireland finds 8-fold Increase in autism diagnosis over the last 20 years. The Mental Elf. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/learning-disabilities/autistic-spectrum-disorder/autism-diagnosis/

Martinez, S., Stoyanov, K., & Carcache, L. (2024). Unraveling the spectrum: overlap, distinctions, and nuances of ADHD and ASD in children. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1387179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1387179

McDonald, T. A. M. (2020). Autism identity and the “lost generation”: Structural validation of the autism spectrum identity scale and comparison of diagnosed and self-diagnosed adults on the autism spectrum. Autism in Adulthood, 2(1), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2019.006

Oxford Centre for Triple Value Healthcare. (n.d.). Critical appraisal skills programme. https://casp-uk.net/

Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. https://emotrab.ufba.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Saldana-2013-TheCodingManualforQualitativeResearchers.pdf

Sandell, C., Kjellberg, A., & Taylor, R. R. (2013). Participating in diagnostic experience: adults with neuropsychiatric disorders. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(2), 136-142. https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2012.741621

Sarrett, J. C. (2016). Biocertification and neurodiversity: The role and implications of self-diagnosis in autistic communities. Neuroethics, 9, 23-36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12152-016-9247-x

Symons, R. (2021). Autism and social anxiety: qualitative research shows how we can help. The Mental Elf. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/learning-disabilities/autistic-spectrum-disorder/autism-social-anxiety/

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC medical research methodology, 8, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC medical research methodology, 12, 1-8. 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

Photo credits

- Photo by Vlad Bagacian on Unsplash

- Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

- Photo by Edu Lauton on Unsplash

- Photo by Jack Anstey on Unsplash

- Photo by Lina Trochez on Unsplash

- Photo by Jason Leung on Unsplash