Refugees fleeing their home countries for safety in high-income host nations are increasingly subjected to hostile post-migration policies aimed at deterring asylum-seekers, such as government withholding of permanent residency visas. Despite this, the number of global asylum seekers continues to increase, with numbers reaching 4.6 million in 2021. The demographic of asylum-seekers has also shifted from predominantly male lone travellers to rising numbers of family-units, meaning more refugee children are growing up under the conditions of visa insecurity in their new countries.

Mental health professionals and researchers share concerns regarding the impact of visa insecurity on children growing up in such conditions, but no previous research has investigated this. For adult refugees, studies show elevated rates of mental health problems in permanent settlers and have established an association between visa insecurity and poorer mental health. Mental health outcomes in refugee children permanently settled with their families in Australia have been found to be comparable to their native counterparts (Lau et al., 2018); however, this finding is limited in that the potential protective effect of permanent residency cannot be distinguished from that of a unified family. New research by Ratnamohan and colleagues (2023) aimed to investigate the impact of visa insecurity on the mental health of refugee children living in Australia.

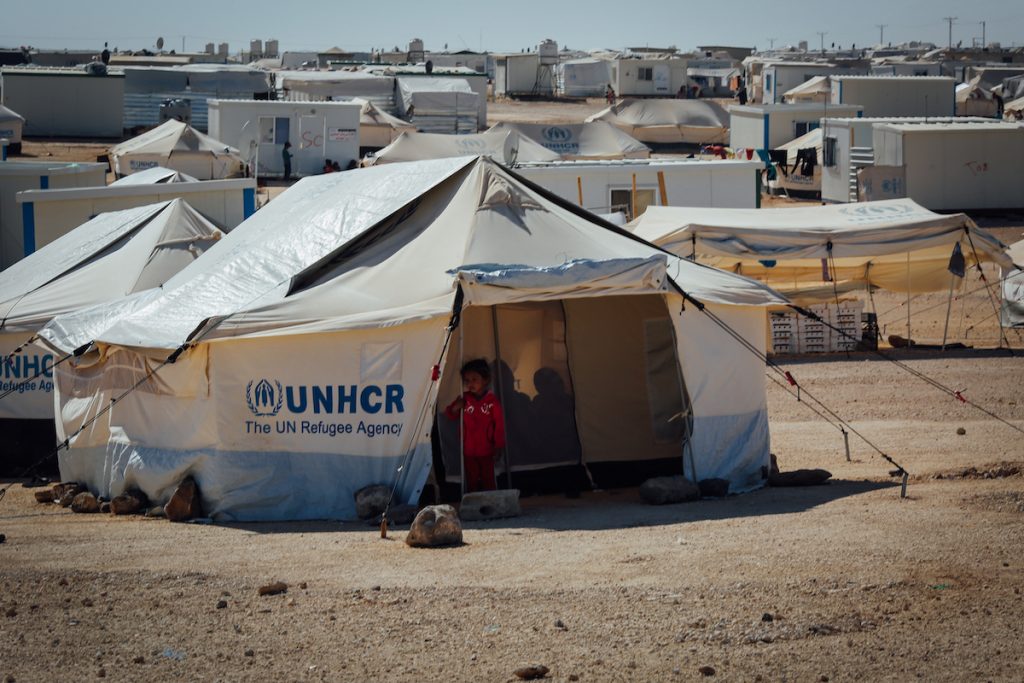

Increasing numbers of refugee children live under conditions of visa insecurity.

Methods

Ratnamohan and colleagues (2023) used a cross-sectional design, drawing samples from two contemporaneous cohorts of refugee children aged 10-18 living in Australia with their families.

The secure residency (SR) sample consisted of 293 children and 199 mothers from the existing ‘Building a New Life in Australia’ cohort, a multi-ethnic nationally-representative sample of refugees who are permanently resettled on humanitarian visas. The insecure residency (IR) sample consisted of 68 children from 43 Tamil asylum-seeking families, recruited from three community-based sites. Two levels of visa security existed within the IR sample: 26 families (40 children) had been granted temporary protection visas and 17 families (28 children) had only bridging visas, the lowest level of protection.

Other exposures measured in the study included maternal post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma exposure (both direct to child and indirect through the family), and post-migration living difficulties. As these constructs were measured differently for each cohort the researchers mapped the data to make the variables comparable. The primary outcome was child mental health problems, measured in both samples using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire.

Analyses made comparisons across the three levels of visa insecurity (permanent protection, temporary protection and bridging visa) and explored both direct and indirect effects of visa insecurity on child mental health problems using path analysis modelling.

Results

The analyses pooled data from 361 refugee children. Apart from the permanent protection visa group being on average one year older than the temporary protection visa group, there were no significant differences in demographics by group.

Group differences: trauma, maternal PTSD, and living difficulties

Analyses found that direct and familial trauma exposure was significantly greater in the IR (insecure residency) sample compared to the SR (secure residency) sample. The prevalence of child direct-exposure to traumatic events was significantly higher in both the temporary protection and bridging visa groups compared to the permanent protection group. Similarly, the number of traumatic events that IR families were exposed to was significantly higher than the amount experienced by SR families, and this was true again for both the temporary and bridging visa groups.

Mothers in the IR sample – in both the temporary protection and bridging visa groups – were found to have greater PTSD symptom scores than mothers in the SR sample. It was also more likely that these mothers were classified as probable cases of PTSD than those in the SR group. For post-migration living difficulties, the bridging visa group reported greater difficulties than the temporary or permanent protection visa groups.

Path analysis of child mental health problems

The path analysis models revealed both direct and indirect pathways to mental health problems in the pooled sample of children. Trauma exposure to the child, PTSD in mothers, and female gender were found to exert a direct path to greater mental health problems for the sampled refugee children.

Visa insecurity imposed an indirect path to child mental health problems; the findings suggested that visa insecurity impacts on the mental health of refugee children through increased living difficulties and maternal PTSD. A significant interaction effect was found between maternal PTSD and visa insecurity, suggesting that the extent of the impact of maternal PTSD on refugee children’s mental health problems is amplified under insecure residency conditions.

Insecure residency was associated with greater trauma exposure, maternal PTSD symptoms, and living difficulties.

Conclusions

Ratnamohan and colleagues (2023) concluded that they had found an association between visa insecurity and poorer mental health in refugee children. This association was regarded to be mediated by the experience of living difficulties in the family post-migration and subsequent maternal PTSD.

The researchers also concluded that the strength of the association between visa insecurity and child mental health problems was moderated by the severity of PTSD in the mothers. The findings suggest that under the conditions of insecure settlement post-migration, asylum-seeking families have a lowered capacity to protect children from the accumulation of stressors, thus a larger proportion of their children are at risk of developing mental health problems.

This research suggests that asylum-seeking families bringing children up under insecure visa conditions have a reduced capacity to foster child resilience.

Strengths and limitations

One of the major strengths of this study is that it is one of the first to the authors’ knowledge to investigate the isolated impact of prolonged insecurity post-migration on the mental health of refugee children. Using two contemporaneous cohorts of refugee children living with their families in Australia, the researchers have found initial evidence that visa insecurity exerts a detrimental effect on child mental health via post-migration stressors and maternal PTSD. The findings are consistent with the literature, as Rostami et al. (2022) found similar results for Iranian and Afghan asylum-seeking families under the same regime in Australia; providing evidence of convergent validity purportedly resolves the issue of ethnicity as a possible confounder in the current study.

Despite the clear strengths of the paper, the existence of a causal relationship between visa insecurity and child mental health problems cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional study design. Although path analysis modelling was employed to suggest a sequential path to child mental health outcomes, the research design limits this assertion due to the data revealing only a snapshot of the sampled children’s mental health at one timepoint.

Other limitations include the study’s exclusion of possible confounding variables in measurement and analysis. For example, while the authors noted a stark difference in the typical entry route to Australia between the IR and SR sample, there was no attempt to control for this in the analysis. Additionally, there was no consideration of the role of paternal PTSD embedded in the study’s design, despite the likely effect of familial trauma on fathers and the subsequent impact on child-rearing. A further limitation is that the generalisability of the paper’s findings is limited due to the range of policies and public reception to refugees in host nations globally, and the diversity of asylum-seeking populations.

Causality cannot be asserted in this study, but the authors provide ground for further research on visa insecurity, accommodation and child mental health.

Implications for practice

The choice by governments to withhold permanent protection visas from families seeking asylum in their nations could be exerting a detrimental effect on the mental health of child refugees. Asylum seekers’ vulnerability to poor mental health due to pre-migration experiences is amplified by the post-migration conditions imposed on them by host-nation policies. Mental health professionals and the general public should feel compelled to campaign for welcoming resettlement policies that protect the mental health of refugee children, supporting them along a trajectory of resilience and success rather than risk – especially in countries accepting an increasing number of asylum-seeking families.

Further research should follow Ratnamohan and colleagues’ (2023) publication to establish a wider evidence base and increase the generalisability of the findings to other parts of the world. Additionally, longitudinal research should provide a longer-term perspective on the effect of prolonged visa insecurity on child mental health. There is scope for further research into the mechanisms involved in the pathways to risk and resilience for children living under conditions of visa insecurity. It is important to specify which aspects of post-migration life protect from or perpetuate the increase in mental health problems for children without permanent resettlement status. Furthermore, the literature should be expanded through exploration of the factors within the family that nurture child and parent wellbeing under insecure visa conditions.

For mental health professionals working in high-income countries with asylum-seeking children and families, this paper and subsequent studies should be considered when formulating presentations of distress. Clinicians should be cognisant of the systemic factors that contribute to and prolong trauma responses, including the hostility of resettlement policies imposed by apparently ‘safe’ host-nations and the current political climate around human and refugee rights. In the context of current and ongoing crises that impact on the global community, it is as vital as ever that the findings of studies such as this one are considered so that mental health professionals can provide appropriate and culturally sensitive interventions and support.

The evidence implies the need for more welcoming resettlement policies for refugees and appropriate provision of support to help refugee children resettle.

Statement of interests

None.

Links

Primary paper

Ratnamohan L, Silove D, Mares S, Krishna Y, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Steel Z. Breaching the family walls: Modelling the impact of prolonged visa insecurity on asylum-seeking children. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2023;57(8):1130-1139.

Other references

Lau W, Silove D, Edwards B, et al. Adjustment of refugee children and adolescents in Australia: outcomes from wave three of the Building a New Life in Australia study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):157.

Rostami R, Wells R, Solaimani J, et al. The mental health of Farsi-Dari speaking asylum-seeking children and parents facing insecure residency in Australia. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022;27:100548.