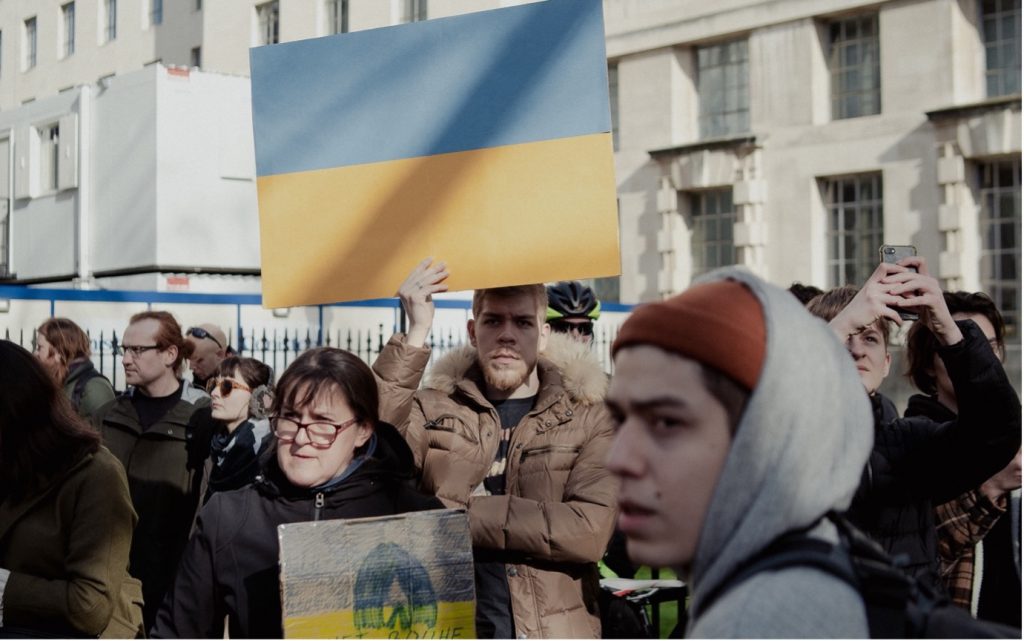

The current Russian invasion of Ukraine, which began on 24th February 2022, has created a dire situation for the 6.5 million children that live there. Over 1,000 children have lost their lives, and frequent attacks on the country’s infrastructure has reduced access to water, electricity, sanitation, and heating (UNICEF, 2022; UNICEF, 2023). An estimated 3.4 million children need urgent humanitarian assistance (OCHA, 2023).

Sadly, this full-scale invasion is not the first conflict between Ukraine and Russia. In February 2014, the Ukrainian region of Crimea was annexed by Russia (BBC, 2014), and pro-Russian separatists took over government buildings in Donetsk and Luhansk (BBC, 2015). They proclaimed these areas as states independent from Ukraine. This series of events involved armed conflict that led to traumatic experiences that civilians, including children, were commonly exposed to.

We know from previous research that a young person’s risk of developing a mental illness is increased when living in war conditions (Charlson et al., 2019). However, not many studies have used the opportunity to compare two regions in the same country, where one is involved in armed conflict. A study by Osokina and colleagues (2022) was carried out in Ukraine between 2016-2017, over two years after Russia’s 2014 invasion, where young people’s risk of developing mental illness was compared in Donetsk, a war-affected region, to an unaffected area called Kirovograd.

The conflict in Ukraine has exposed millions of children to traumatic events that may affect their risk of developing mental illnesses.

Methods

The researchers used a case-control study to investigate the potentially elevated risk of mental health problems in children within war-affected regions by comparing them to children in a region not affected by war. They approached schools in Donetsk, an area of Ukraine that was affected by the Russian invasion, and Kirovograd, an area not impacted. Kids in these schools, who were aged between 11-17 years old, were then asked to participate in the study which would involve them filling out questionnaires about their mental health. These included a survey on demographic information and the number of traumatic events the child had experienced, the Harvard Trauma Questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7). The researchers recruited 1,463 young people from schools in Donetsk and 1,303 were recruited from Kirovograd. After collecting the questionnaire results, the researchers carried out statistical analyses to identify whether there were any significant differences on scores between the two groups. The expectation was to judge whether children living in a war-affected region were more at risk of mental health problems compared to the region not affected by war.

Results

All the young people involved in the study (carried out in Ukraine between 2016-2017) had experienced at least one war-related event, though those living in the Donetsk region witnessed significantly more events. For example, most children from the Donetsk group (60.2%) had witnessed attacks by armed forces, heavy weapons, artillery fire, or explosions. This was compared to 0.5% of children in Kirovograd. Also, when comparing the demographic information, those in the war-affected region were more likely to have a father who was unemployed.

The study found, as expected, that children in the war-affected region had significantly higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety when compared to children in the region not affected by war. Children from Donetsk were over 4 times more likely to suffer from PTSD, over 3 times as likely to have severe anxiety, and nearly 3 times as likely to experience moderately severe, or severe depression.

These results follow a similar trend from other studies looking at mental health problems in children within war-affected regions, though the prevalence rates were not as large as previously estimated. The researchers guessed this might be because the study was carried out quite soon after the Russian invasion, which means that it may have been too early to measure the full impact of the war on mental health.

Children living in war-torn regions in Ukraine appear to be more at risk of developing PTSD, depression, or anxiety.

Conclusions

The researchers concluded that living in a war-affected region in Ukraine increases the risk of being exposed to traumatic events, particularly ones linked to armed conflict. This incidentally raises the risk of developing mental health problems, particularly PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

A young person living in a war-affected region has a high risk of experiencing traumatic events, potentially leading to mental health problems.

Strengths and limitations

Having two groups to compare against each other that are both from the same country helps to naturally control for a significant portion of the potential effects of culture or geographic location on these results. If the researchers instead compared the Donetsk group with a peaceful region outside of Ukraine, it would be difficult to rule out the potential effect of culture on mental illness risks. This is a great strength of the study. Secondly, the researchers were able to collect a large sample of young people to take part in the study. This gives us some confidence that the results could be representative of other war-affected areas.

The study is limited by the fact that only children who attended school could be part of the research. Although it’s likely most young people attend school, there is still a selection of those who don’t. This group might have distinct characteristics from those who do attend a school which may mean the results of this study wouldn’t reflect their experience. Also, Osokina and colleagues used a cross-sectional method, meaning that data were collected at a single point in time. This makes it difficult to explore any potential causal factors. Future research that takes advantage of longitudinal designs would be a huge benefit for learning more about the effect of war on mental illness in young people.

Future longitudinal studies could explore the causal relationship between experiencing armed conflict and developing a mental health problem.

Implications for practice

It appears likely that children from war-affected regions are at a significantly higher risk of developing PTSD, depression, or anxiety. Clinicians who work with this population, therefore, need to keep in mind this reality. Refugees from war-torn areas may require more urgent support for their mental health, and mental health workers need to be conscious of how the nature of their trauma interacts with their symptoms. For example, young people experiencing war first-hand may have witnessed the death of loved ones, been forced to fight against their will, or had to evacuate their homes. It is important these potentialities are considered when formulating a treatment plan for these youth.

Alongside this, it would be useful for healthcare workers to be aware of the cultural differences between the UK and regions where war is a current event. Young people from these areas might have been exposed to the stigma surrounding mental illness and may require further sensitivity when supporting them. Young refugees from war-affected areas will also benefit from clinicians and healthcare leaders being aware of the potentially higher risk of mental health problems. Asylum seekers may benefit from health campaigns that encourage them to seek support for their mental health, as well as their past experiences being explored during treatment. Moreover, commissioners should do everything they can to ensure that services have capacity to support people affected in their areas.

Clinicians should consider whether their young clients have experienced living in an area affected by war before formulating their treatment plan.

Statement of interests

The author has no affiliations to mention.

Links

Primary paper

Osokina, O., Silwal, S., Bohdanova, T., Hodes, M., Sourander, A., & Skokauskas, N. (2023). Impact of the Russian Invasion on Mental Health of Adolescents in Ukraine. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 62(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2022.07.845

Other references

BBC (2014). Ukraine: Putin signs Crimea annexation. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-26686949

BBC (2015). Ukraine conflict: Why is east hit by conflict? BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-28969784

Charlson, F., van Ommeren, M., Flaxman, A., Cornett, J., Whiteford, H., & Saxena, S. (2019). New WHO prevalence estimates of mental disorders in conflict settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 394(10194), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30934-1

OCHA (2023). Ukraine Humanitarian Response—Key Achievements in 2022. https://reports.unocha.org/en/country/ukraine/

UNICEF (2022) Ukraine Humanitarian Situation Report, December 2022. from https://www.unicef.org/documents/ukraine-humanitarian-situation-report-december-2022

UNICEF. (2023). Ukraine (UKR)—Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality. UNICEF Data. Retrieved 4 April 2023, from https://data.unicef.org/country/ukr/

Photo credits

- Photo by Chuko Cribb on Unsplash

- Photo by Karollyne Hubert on Unsplash

- Photo by Thiago Rocha on Unsplash

- Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash