This is a posting in two connected parts. The article to be reviewed has had the (mis)fortune of attracting considerable press coverage, as its headline finding links the themes of young people, violence, crime, drugs and mental health. Time to sound your Daily Mail claxon or post your bad science alert to Ben Goldacre.

Whilst my approach to the research paper is one framed by objectivity and research quality, my approach to the media coverage will be more pithy but equally important, since the vast majority of public awareness of the scientific paper will be framed by the interpretation of the ‘science journalists’ working in our tabloids and broadsheets.

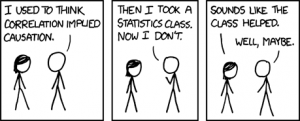

The important part for the Mental Elf is the paper summary itself and in assessing the study I hope to illustrate how a seemingly straightforward correlation analysis can actually be rather complicated and unfortunately open to the conflation of causation with correlation.

Correlation is not causation http://xkcd.com/552/

The research paper

In this national level study, the authors looked at data covering the entire population of Sweden aged fifteen or over (7,917,854 people) over a three year period. They looked specifically at the rates of certain types of charged and prosecuted criminal activity, the diagnosis of a range of mental health conditions, the prescription of SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors – antidepressants) and other psychiatric medications, and demographic data.

The aim of the study was to probe further into the poorly established relationship between SSRIs and violent crimes, which to date has been mostly founded on individual cases or as an extrapolation of concerns about SSRIs and suicidality. Such associations, as the authors point out, do not incorporate research evidence suggesting that the prescription of SSRIs might actually prevent or reduce violent activity.

Sweden is a useful country for this study, because the rates of SSRI prescribing are comparable to the USA and higher than most European countries, and rates of violent crimes are also similar to the United States. That the authors take care to point this out shows their consideration of some of the questions readers might raise about generalisability and this careful attention to detail characterises what is a very thorough scientific paper. The inevitable downside of this is that it is a very dense read; a trade-off I am happy to take, but one which probably contributes to the over-simplified press summaries.

This high quality cohort study investigated the association between violent crime and SSRIs in Sweden. (It’s not all islands and clear blue skies you know).

Methods

The method of analysis used was a between-individual Cox proportional hazards regression. For those unfamiliar with this technique (which included me before reading this paper), this is like an odds ratio analysis, and enables the researchers to look at the relative risk of something occurring in one population in comparison to another population.

In their analyses, the researchers then incorporated a within-individuals proportional analysis to separate out, for each individual in the ‘SSRI’ group, time periods when they had an active prescription from times when they did not. This was used to designate people as taking or not taking SSRIs, which is a problematic assumption, especially when we consider the evidence concerning poor medication adherence in young people.

Results

- Of the population under analysis, 856,493 people were prescribed an SSRI at some point in the study window of 2006-2009.

- Of these, 8,377 people (1.0%) were found guilty of committing a violent crime during the study; 0.6% of the non-SSRI population were convicted of a violent crime in the same period.

- It is of note that in the non-SSRI population, the percentage of people prescribed another psychiatric medication during the study was 19.3%, as compared to 75.1% of the SSRI group.

- A further key difference between the two populations was the difference in substance use disorder diagnoses, which were present for 2.7% of the non-SSRI group and 9.1% of the SSRI group.

- In the 15-24 year old bracket, the hazard ratio for being cautioned for alcohol intoxication was 1.98 (p<0.001).

The researchers did address some of the potential limitations before coming to their conclusions:

- They looked at non-specific medication/outpatient factors by assessing whether people taking diuretics during the research period had any differential likelihood of being involved in violent crime, and they did not (HR=0.80, 95% CI = 0.67-0.95, p=0.012).

- They altered the window of consecutive prescriptions from six months to three months, and again this had no bearing on outcomes.

The two main findings, in the views of the authors, are:

- A lack of a significant relationship between SSRI use and violent crime convictions in people aged 25 and older, in a very large population over several years

- A significant relationship between SSRI use and violent crime convictions in 15-24 year olds that requires further investigation in order to understand what contributes to this correlation

The study did identify a link between SSRI use and violent crime in 15-24 year olds.

The first of these, being a ‘non-result’, is perhaps challenging for the authors to sell to readers; our eyes and brains tend to be drawn to relationships, yet this lack of correlation is not only robust but also potentially very meaningful to drug companies and those adults currently prescribed SSRIs.

The second finding does indeed warrant further investigation, although the press response shows how hard it can be to advise moderation even where it is clearly needed. Although the research design allows for control of time-varying factors and within-individual changes, there are difficulties with a number of the measures being used. For example, using prescriptions to measure SSRI use is inherently problematic, since we cannot assume that someone with a prescription is necessarily taking the medication as directed.

Some of the more interesting findings are found when the authors break down the overall results by different variable categories:

- When broken down by type of SSRI, the hazard ratios for convicted violent crime are easily strongest in the 15-24 age group for:

- Sertraline (1.66, p=0.001) and

- Escitalopram (2.44, p=0.001);

- Paroxetine comes in with a reversed hazard ratio for convicted violent crime of 0.59 (not significant).

- Pertinently, the hazard ratios for non-SSRI medications for convicted violent crime in 15-24 year olds were considerably elevated for:

- Venlafaxine (2.46, p=0.004) and

- Duloxetine (2.12, p=0.054).

The authors consider that the differences noted between SSRIs and violent crime convictions could be due to different efficacies or different half-lives of the drugs.

Also important to note is the finding that the significant relationship between SSRI use and violent crime in 15-24 year olds only holds at low SSRI dosage, and not at higher doses. Because we do not know anything about the individual cases, we cannot say whether this is a sign of inadequate dosage; I was unable to work out if these lower dosage levels were disproportionately related to individuals only just starting on SSRIs, and if there would be a potential elevated risk level at first contact with medical support.

The hazard ratios for different antidepressants are clearly presented in the open access paper.

If it bleeds, it leads… (the media coverage)

September 15th and 16th saw a flurry of articles published in response to the SSRI paper. In an alarming illustration of headline-article contradiction, readers of The Sun were greeted by a topline of:

Prozac kids go violent… Youngsters given common antidepressants such as Prozac are 43 per cent more likely to commit violent crimes, according to researchers

undermined entirely five sentences in with the revelation that lead researcher Seena Fazel:

…says it is too early to blame dangerous behaviour on the medication.

Possibly three sentences too late for several people!

Other newspapers were more balanced, less alarmist; yet the articles were all of the same format:

- Opening with: SSRIs = violence in youth

- Ending with: two sentences of caution

There’s nothing surprising in this and I would hazard some socio-linguistic researchers have analysed the prevalence of this format in all sorts of media presentations. The problem in this case is that it really is misleading and potentially very damaging to (and for) a somewhat stigmatised group in society.

On a more positive front, several articles were of substantial length and had sought not only further comment from Professor Fazel, but comments from other researchers active in this field. Several writers highlighted the importance for people to adhere to their current antidepressant medication, although it is difficult to marry this up with all the apparent dangers of said medication portrayed three inches further up the page.

Conclusion

This is a valuable paper in terms of its scope and scientific rigour, but its reassuring main message on the lack of a link between violent crime convictions and SSRI prescriptions has been somewhat lost in the retelling.

With attention grabbing headlines flying around, it is sometimes hard to see the wood for the trees.

Links

Primary paper

Molero Y, Lichtenstein P, Zetterqvist J, Gumpert CH, Fazel S (2015) Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Violent Crime: A Cohort Study. PLoS Med12(9): e1001875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001875

Other references

SSRI antidepressants and violent crime. Science Media Centre briefing, 15 Sep 2015.

No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s http://t.co/jqoGYQmBVd #MentalHealth http://t.co/Fb5O4wIXN9

Today we grab no headlines about young people, violence, crime, antidepressants and mental health http://t.co/WYbai5ryax

@Mental_Elf Good points made about the challenges of dealing with the media – we were assisted greatly by the @SMC_London. Really helpful.

@Mental_Elf And the impression I gained is that the headline writers are different from the health reporters – so there can be a disconnect

@Mental_Elf see also the thoughtful blog by @CoyneoftheRealm on the issue and the media handling: http://t.co/PJ91YudwzP

Coyne’s blog r=0.9 correlation with post writer’s feeling of inadequacy, in ironic demonstration of correlation representing causation. It’s an excellent blog, thanks for sharing it and being involved in the discussion.

Contrast my coverage of SSRI’violence study http://t.co/o9Q553lLwG with @Mental_Elf http://t.co/flQSlCS5GJ https://t.co/Tk4Z6Brkam

#Antidepressants #YoungPeople #ViolentCrime

Time to see the wood for the trees?

http://t.co/WYbai5ryax http://t.co/eksXrOEkqg

Our blog about @seenafazel’s high quality cohort study investigating association between violent crime & SSRIs http://t.co/WYbai5ryax

@Mental_Elf @seenafazel er was it a cohort study? Or analysis of registry data?

@vijaykrishnan @Mental_Elf the two are not mutually exclusive

@seenafazel @Mental_Elf perhaps not. Big data blurs boundaries? Difference in the kind of measurement though-definitely post hoc here

@vijaykrishnan @Mental_Elf that’s right for many exposures and outcomes but less so when validated, reliable and ‘hard’ (e.g. crimes)

RT @DrDannyPenman: RT @Mental_Elf: #Antidepressants #YoungPeople #ViolentCrime

Time to see wood for the trees? http://t.co/lJ6gJGurEV http:…

No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s https://t.co/C17vvY2iSb via @sharethis

RT @Mental_Elf: .@PLOSMedicine study concludes: link btwn SSRI use & violent crime in young people needs validation in other studies http:/…

RT @Mental_Elf: Hello @senseaboutsci @evimatters Have you seen our blog today on SSRIs and violent crime? http://t.co/WYbai5ryax

Don’t miss: No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s http://t.co/WYbai5ryax #EBP

@Mental_Elf @suicideresearch ?missing s/thing? ?link b/w SSRI&alcohol use/drug & violent crime w/suicide? DIR w/alcohol/substance&SUI

Interesting review: No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s https://t.co/DVG5c3QTP9 via @sharethis

No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s https://t.co/uFtMANmqO9

Great blog by the @Mental_Elf explaining the evidence around #SSRI antidepressants and #violentcrime http://t.co/xLOX67v0xV

No link between #SSRI use & violent crime in over 25s http://t.co/gIDDlB7XSS @Mental_Elf looks at the #evidence & resulting press coverage

Great article from @Mental_Elf. Thanks! No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s https://t.co/JFdeezaHu4 via @sharethis

No link between SSRI use and violent crime in over 25s https://t.co/QF6gwNCatj via @sharethis.

@Mental_Elf That’s good, but it’s like fat-free catsup.

If SSRI use is linked to violence in < 25s, the most violent age group, it’s bad.