Health action plans for people with learning disabilities have been advocated in English policy since 2001 (Department of Health 2001). They were conceived as a record to be held by the person, in a format to suit the individual, to help the person understand their own health and the actions agreed to help them improve or maintain their health. Health action plans were to be based on comprehensive health checks.

Evidence for the effectiveness of health checks has been systematically reviewed (Robertson et al., 2010) and a number of the studies reviewed included the production of health action plans. The effectiveness of such plans was not reviewed separately from the effectiveness of the health checks.

The concept of health action plans has evolved since 2001, with recognition that practitioners need a concise statement of the person’s health problems and planned actions and that this may not be in a format that is easy for the person to understand themselves.

For example, templates have been set up in general practice information systems; these could be used to generate a record held by the person, but their primary purpose is to act as a record for the practice. Production of a health action plan based on an annual health check is part of the current Enhanced Service for people with learning disabilities in the 2014/15 General Medical Services contract.

Use of hospital passports was strongly advocated in the Michael report as a reasonable adjustment to improve the quality of health care

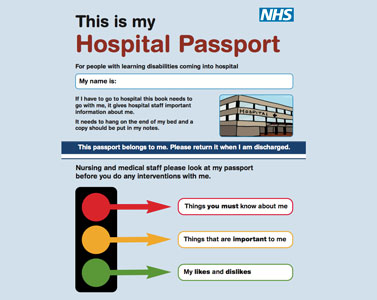

Alongside the health action plan derived from a health check, the use of hospital ‘passports’ has also developed to improve communication of important information to hospital staff. Ideally such passports are produced with the person and will contain information that is important to them (such as preferences) as well as information about them that might be supplied by health professionals (e.g. a record of health problems, prescribed medication, health risks).

Use of hospital passports was strongly advocated in the Michael Inquiry report (Michael 2008) as a reasonable adjustment to improve the quality of health care. This was also a recommendation from the report of the Confidential Inquiry into premature deaths of people with learning disabilities (CIPOLD) . The CIPOLD study found no evidence that hospital passports had “supported medical staff in coordinating the needs of a person with multiple co-morbidities”, but there was “evidence to suggest that such documents helped nursing staff to understand a person’s needs and provide person-centred nursing care”.

The CIPOLD report also commented on the use of Health Action Plans in primary care, noting that “they seemed to have been used with some degree of effectiveness to facilitate better personal control, as an aide-memoire to the person themselves about the actions that they should be taking to maintain good health” or to document their wishes.

Summary of the systematic review of hand-held records

The authors conducted a systematic literature search for papers published between 1980 and 31 August 2013. They also consulted established researchers in the field to identify any articles that might have been missed. Search terms relating to intellectual disability were combined with terms such as ‘hand-held health record’ or ‘passport’. They found seven papers that met their criteria; six of these were from just two research centres – one in Australia and one in England.

Based on review of the papers identified, the authors concluded that hand-held health records were well accepted by people with learning disabilities and had led to increased discussion and increased awareness about health issues. However, they found no evidence of documented improvements in short-term health care activity. They also noted that the studies reviewed did not include longer term follow-up.

Hand-held health records were well accepted and led to increased discussion and increased awareness about health issues, but with no evidence of improvements in short-term health care activity

Strengths and limitations of the research

It is always useful to challenge established beliefs about what constitutes good practice and the authors noted the paucity of evidence for improved clinical outcomes with other groups of adults. It would have been useful if they had also commented on the strength of evidence from children’s health care, where family-held records have been established for many years.

It is possible that the authors’ search strategy excluded some relevant studies. Their search terms did not include ‘health action plan’, for example. They excluded electronic records on the grounds that these are not “physically located with the individual”. It is not clear whether this may have resulted in the exclusion of studies involving records that the individual might hold on a device such as tablet computer. It is notable that the studies selected for inclusion did not include the CIPOLD report, which was published within the timeframe and did comment on both health action plans and hospital passports. This inevitably raises questions in the reader’s mind about whether other relevant research was omitted.

A personal concern of this reader was that the authors use the term ‘carer’ to mean both family carers and paid staff. This may reflect usage in the studies reviewed, but should nonetheless be challenged. Many of the issues and concerns will be the same for family carers and for paid staff; however, there are also differences between family members and staff in how they interact with health services and it is helpful to be clear which group is being discussed.

Conclusion

Health action plans and hospital passports are widely accepted and promoted as good practice. It is good to have research evidence that they are well accepted and can promote increased awareness of health issues in people with learning disabilities, while it is salutary to be reminded that more research is needed to show whether there is any long term impact on health outcomes.

Link

Nguyen, M., Lennox, N. and Ware, R. (2014), Hand-held health records for individuals with intellectual disability: a systematic review. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58: 1172–1178 [abstract]

References

Confidential Inquiry into premature deaths of people with learning disabilities (CIPOLD): Final report

Department of Health (2001) Valuing People: A New Strategy for Learning Disability for the 21st Century.

Michael, J. (2008) Healthcare for all: report of the independent inquiry into access to healthcare for people with learning disabilities

Robertson J, Roberts H & Emerson E, (2010) Health Checks for People with Learning Disabilities: A Systematic Review of Evidence, Improving Health and Lives, Learning Disabilities Observatory

RT @LearningDisElf: Hand held health records did not improve short term health outcomes according to review http://t.co/DfMfj81UnR

From @LearningDisElf: how to improve identification of health problems among people with learning disabilities: http://t.co/Y0pABSgfib

The Learning Disabilities Elf liked this on Facebook.

Today Alison Giraud-Saunders on a systematic review of hand-held health records for ppl w/ intellectual disability http://t.co/DfMfj8jvMr

RT @Aspirantdiva: How to improve identification of health problems among people with learning disabilities: http://t.co/UmWonVCNAo

Health action plans and passports well used and accepted by PWLD but are they hitting the spot? http://t.co/bgSaM4QhFw

The Michael report advocated use of hospital passports as a reasonable adjustment to improve quality of health care http://t.co/DfMfj8jvMr

Hand-held health records were well accepted & led to increased discussion & increased awareness about health issues http://t.co/DfMfj8jvMr

The Michael report advocated use of hospital passports as a reasonable adjustment via @LearningDisElf… http://t.co/bejcLBM2Uc

More research into health action plans & hospital passports is needed to measure long-term impact on health outcomes http://t.co/DfMfj8jvMr

Hand held health records increased awareness of health issues but no evidence of improvements in short-term – http://t.co/zV3hNMjlbx

Hand held health records did not improve short term health outcomes according to review http://t.co/DfMfj8jvMr #EBP

Handheld health records increase awareness of health but no evidence of improved health care http://t.co/2iO5XoMGVR @sharethis

Hand held health records increased awareness of health issues but no improvements in short-term health care activity http://t.co/odNJE55ah2

I have recently hit a crisis in caring for my son with Severe Learning Disabilities relating to behaviour then a link to health finding errors in the services relating to GPs referral, waiting times, attitudes, out of hour services and areas, hospital visits relating to hospital pass port. I am now as a Carer challenging the errors with in a link I am in with meetings in Partnerdhip Boards and Carers meetings. I demand changes and I will be working at this. Also have Health watch link to this. More needs to be done. I have had a year of hell and stress even longer.

http://t.co/HQoCGsdd8p… http://t.co/MJebMA7AgM