There is now greater recognition amongst academics, clinicians (Karatzias et al., 2017), and the general public regarding the long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). Its life-defining after-effects were portrayed with searing honesty in the recent drama The Virtues, written and directed by Shane Meadows, who movingly shared his own experiences of CSA in a recent interview.

A 2011 meta-analysis of 217 studies placed the global prevalence of CSA at approximately 12% (Stoltenborgh et al., 2011). This is likely an underestimate due to underreporting (Widom & Morris, 1997), as well as methodological differences across studies. For context, the prevalence of heart disease, the leading global cause of death, is approximately 31%.

Not only is CSA common, but its effects are wide-reaching, being associated with a multitude of adverse health outcomes, including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), substance abuse, eating disorders, schizophrenia, and sexual dysfunction (Sapp & Vandeven, 2005). However, these associations are based on academic studies of differing sample sizes, methodologies, and even differing definitions of childhood sexual abuse.

There have been numerous meta-analyses, but to date no one has comprehensively assessed the strength and quality of evidence for links between CSA and subsequent outcomes. Recently published in the Lancet Psychiatry (Hailes et al., 2019), a new umbrella review (a synthesis of meta-analyses) aimed to evaluate the current literature regarding CSA and long-term outcomes.

To date, no one has comprehensively assessed the strength and quality of evidence for links between childhood sexual abuse and subsequent outcomes.

Methods

The authors were interested in all health, psychosocial, and psychiatric outcomes (after 18 years of age) of childhood sexual abuse (occurring before the age of 18). Multiple databases were searched for meta-analyses of observational studies, both published and grey (non-academic) literature up until Dec 31, 2018. Search keywords covered different possible terms referring to CSA (e.g. child molestation, incest, rape).

When meta-analyses reported data from the same studies, the more up-to-date meta-analysis was included. Studies were excluded if outcome data for CSA were not properly separated from other types of abuse. Outcome data was limited to specific diagnoses and symptoms (e.g. Anxiety), but not subtypes (e.g. social phobia).

Quality of the included meta-analyses was evaluated using the AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews). Publication bias (excess statistical significance and small study effects) was also assessed.

In order to make outcomes comparable, odds ratios were computed from effect sizes and confidence intervals. Odds ratios (ORs) offer a standardised measure of the strength of association between exposure (to CSA) and outcome.

Results

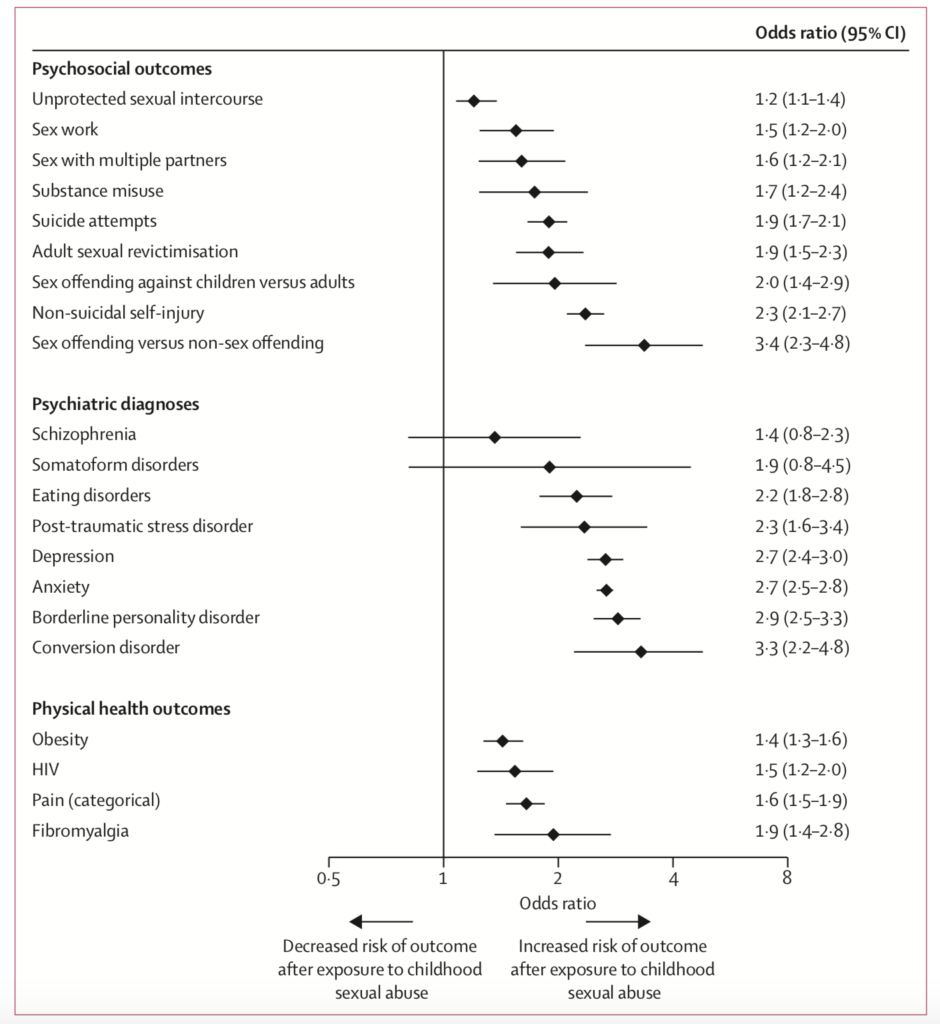

Nineteen meta-analyses including 559 primary studies, covering 28 outcomes in 4,089,547 participants were included. CSA was associated with 26 of 28 outcomes:

- 5 of which were associated with small ORs (less than 1.7)

- 21 of which were associated with medium ORs (between 1.7 and 3.5)

- No outcome was associated with a large OR.

The most strongly associated psychiatric outcomes were conversion disorder, borderline personality disorder, anxiety, and depression. However, data quality was low for the meta-analyses on borderline personality disorder and anxiety, and moderate for conversion disorder.

By contrast, the systematic reviews for schizophrenia, PTSD, and substance misuse were assessed as being of high quality.

Figure 2: Risk estimates of long-term outcomes following childhood sexual abuse (Hailes et al., 2019)

Implications

The consistent finding that childhood sexual abuse (CSA) is associated with detrimental long-term effects in a number of domains reinforces the need for a more nuanced understanding of the biological, psychological and social mechanisms informing our health. Researchers trying to integrate the wealth of research on the effects of trauma on physical and mental health often refer to dysfunction in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Nemeroff & Binder, 2014). Another popular conceptual framework is that of systemic inflammation of the immune system following trauma (Danese & Baldwin, 2017). Both theories involve the role of chronic stress, and how this impacts upon cortisol function. At present these are explanatory frameworks, and the exact causal mechanisms linking CSA to obesity, for example, remain unclear.

To some, a potentially surprising finding will be the now well-established link between CSA and Schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder. There has been a considerable sea change regarding the causal explanations for psychosis (Murray, 2017); what was once seen primarily as a genetic or neurologically-based illness is now viewed as one heavily informed by trauma, poverty, and discrimination (Morgan & Gayer‐Anderson, 2016). It is now increasingly clear that exposure to trauma is a consistent risk factor for voice-hearing in clinical populations (Luhrmann et al., 2019).

To some, a potentially surprising finding will be the now well-established link between childhood sexual abuse and schizophrenia.

Despite the wide range of outcomes showing a moderate link to CSA, only three had supporting evidence of high quality; PTSD, schizophrenia, and substance misuse. This is not to say that the remaining associations are not there, simply that the quality of evidence thus far has not been strong enough to make these links unequivocal. For outcomes with a poorer evidence base, limitations included publication bias and considerable methodological variation (heterogeneity) between studies. The authors recommend higher-quality empirical studies and meta-analyses for those outcomes whose evidence-base remains low (borderline personality disorder and anxiety) to moderate (conversion disorder).

Another recommendation the authors make is to increase the number of prospective studies, given the overrepresentation of retrospective studies dependent on adults’ self-reported recollections of childhood abuse. Many factors can impact upon the fidelity of one’s recollections, such as how an event is encoded into memory, and the social and emotional context in which it is remembered (Newbury et al., 2018). These factors can variously lead to under- or over-reporting in retrospective studies (Baldwin et al., 2019).

Prospective studies provide greater clarity with regards to determining causality, by routinely collecting data from a random sample of children over time, and observing outcomes in those who experience CSA. However, in a published commentary of the review (Sanci, 2019), it is argued that prospective studies are not only expensive and time-consuming, but pose ethical challenges. Routinely interviewing children and caregivers may be needlessly distressing, and with medical record examination and researcher observation, prospective measures are criticised for under-detection of CSA (not all abuse is recorded, caregivers may withhold information or be unaware, etc.).

Furthermore, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis on the degree to which prospective and retrospective studies of CSA agree with each other found that they are not interchangeable (Baldwin et al., 2019). Worryingly, both approaches appear to identify distinct groups of abuse victims that do not overlap with one another. Hence, Sanci recommends that future studies employ both prospective and retrospective measures of CSA.

Prospective and retrospective research studies on childhood sexual abuse appear to identify distinct groups of abuse victims that do not overlap with one another.

Regardless, based on this review’s findings, it is clear that effective approaches to identification and treatment of abuse are necessary. The authors recommend better screening by physicians, as well as school-based programmes aimed at improving recognition, reporting, and protection against CSA. Sanci’s commentary warns that these recommendations are unlikely to change the “siloed approaches to identification, prevention, and management of childhood sexual abuse across the health, policy, education, legal, and welfare sectors, which all interface with vulnerable families”.

For true systemic change to occur there must also be research dedicated to how to effectively translate scientific findings into policy. In this way, scientific knowledge about the pathways from CSA to long-term outcomes would be reflected in system-wide policies, affecting all institutions, and hopefully stemming a grave public health issue.

The authors recommend better screening by physicians, as well as school-based programmes aimed at improving recognition, reporting, and protection against childhood sexual abuse.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Links

Primary paper

Hailes HP, Yu R, Danese A, Fazel S. (2019) Long-term outcomes of childhood sexual abuse: an umbrella review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Oct;6(10):830-839. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30286-X. Epub 2019 Sep 10.

Other references

Baldwin, J.R., Reuben, A., Newbury, J.B., & Danese, A. (2019). Agreement between prospective and retrospective measures of childhood maltreatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry, 76(6), 584-593.

Danese, A., & Baldwin, J.R. (2017). Hidden wounds? Inflammatory links between childhood trauma and psychopathology. Annual review of psychology, 68, 517-544.

Karatzias, T., Cloitre, M., Maercker, A., Kazlauskas, E., Shevlin, M., Hyland, P., Bisson, J.I., Roberts, N.P., & Brewin, C.R. (2017). PTSD and Complex PTSD: ICD-11 updates on concept and measurement in the UK, USA, Germany and Lithuania. European journal of psychotraumatology, 8(sup7), 1418103.

Luhrmann, T.M., Alderson-Day, B., Bell, V., Bless, J.J., Corlett, P., Hugdahl, K., Jones, N., Larøi, F., Moseley, P., & Padmavati, R. (2019). Beyond trauma: a multiple pathways approach to auditory hallucinations in clinical and nonclinical populations. Schizophrenia bulletin, 45(Supplement_1), S24-S31.

Morgan, C., & Gayer‐Anderson, C. (2016). Childhood adversities and psychosis: evidence, challenges, implications. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 93-102.

Murray, R.M. (2017). Mistakes I have made in my research career. Schizophrenia bulletin, 43(2), 253-256.

Nemeroff, C.B., & Binder, E. (2014). The preeminent role of childhood abuse and neglect in vulnerability to major psychiatric disorders: toward elucidating the underlying neurobiological mechanisms.

Newbury, J.B., Arseneault, L., Moffitt, T.E., Caspi, A., Danese, A., Baldwin, J.R., & Fisher, H.L. (2018). Measuring childhood maltreatment to predict early-adult psychopathology: comparison of prospective informant-reports and retrospective self-reports. Journal of psychiatric research, 96, 57-64.

Sanci, L. (2019). Understanding and responding to the long-term burdens of childhood sexual abuse. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(10), 795-797.

Sapp, M.V., & Vandeven, A.M. (2005). Update on childhood sexual abuse. Current opinion in pediatrics, 17(2), 258-264.

Stoltenborgh, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M.H., Euser, E.M., & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J. (2011). A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child maltreatment, 16(2), 79-101.

Widom, C.S., & Morris, S. (1997). Accuracy of adult recollections of childhood victimization, part 2: childhood sexual abuse. Psychological assessment, 9(1), 34.

Thank you, Raphael! It’s very interesting.

The link between CSA and obesity has been hypothesised for a long time in psychodynamics. The young person who has experienced CSA may, through trying to make sense of the why this happened to them, believe it is in part because of their appearance. This is also often used explicitly by the abuser (e.g. “you’re so beautiful”) .

As a result, the young person becomes obese as a defense to make themselves less appealing to potential future predators and threats.

How such theories can be “proven”, particularly through the obsessive world of quantitative data, is near impossible.

Nonetheless, it remains a helpful framework for understanding some of our clients actions and unspoken motives

This study was helpful and painful to read at the same time. The link between CSA and anxiety and depression is quite prevalent if we look around. The kids constantly think about the trauma and get depressed. I wish parents would save their children from this hideous memory to haunt them. I cannot stress enough on the fact that we need to make sure our kids are safe when we are not around them. Most of the time, the rapist is from one of the relatives, servants, or someone the parents highly trust. I wish they would never trust people blindly and leave their kids alone when they have to go somewhere.This study was helpful and painful to read at the same time. The link between CSA and anxiety and depression is quite prevalent if we look around. The kids constantly think about the trauma and get depressed. I wish parents would save their children from this hideous memory to haunt them. I cannot stress enough on the fact that we need to make sure our kids are safe when we are not around them. Most of the time, the rapist is from one of the relatives, servants or someone the parents highly trust. I wish they would never trust people blindly and leave their kids alone when they have to go somewhere.