Many mental health problems affecting adults have their roots in childhood and adolescence. As we gain greater understanding of foetal and early infant development, and develop better assessments, it becomes clearer that even this very early period of life holds importance for later health and wellbeing – right through adult life.

However, for early intervention to work, effective interventions have to be available and, at present, the evidence for the effectiveness of early interventions that actually make a difference to mental health is extremely limited. There is evidence from randomised controlled trials that interventions such as the Nurse Family Partnership (NFP) and Video Feedback to Promote Positive Parenting (ViPP) can improve some outcomes (Juffer et al, 2007; Groeneveld et al, 2011), however the evidence for mental health outcomes is sparse.

In the UK, Parent Infant Psychotherapy (PIP) is strongly promoted as a solution for many difficulties in infancy and is recommended in an increasing number of policy documents, including the important Critical 1001 Days Manifesto (Leadsom et al, 2014). However, there have been few systematic attempts to critique the evidence for PIP.

This new Cochrane systematic review, conducted by Professor Jane Barlow and colleagues, is therefore timely and important (Barlow et al, 2015). It was conducted with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of PIP in relation to a range of primary outcomes; parent mental health, infant mental health (including attachment) and the parent-infant relationship.

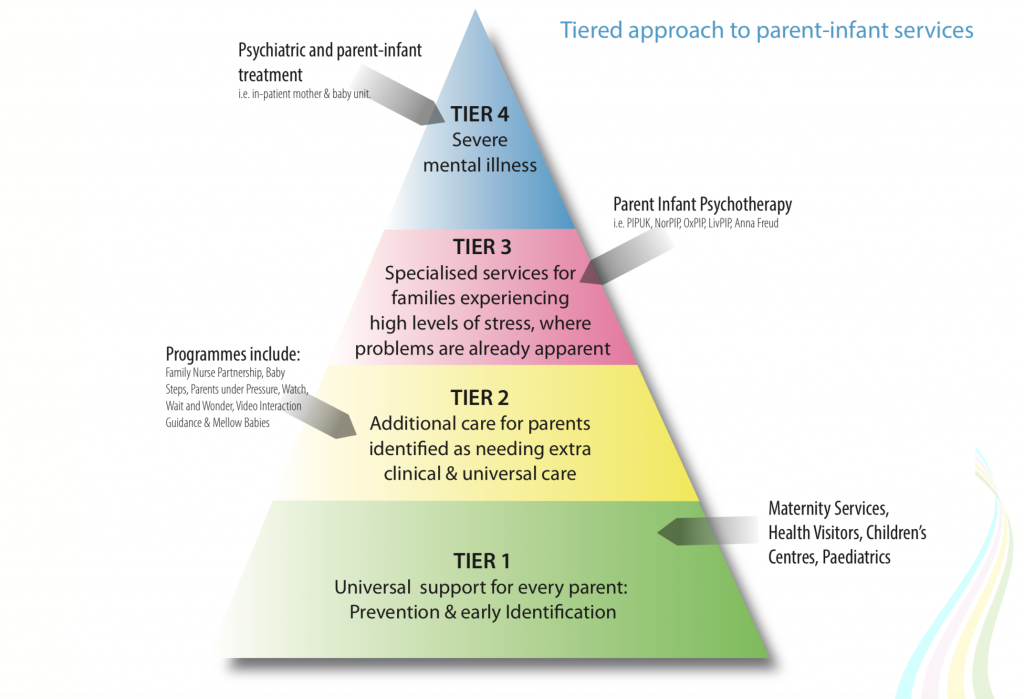

The 1001 days manifesto includes Parent Infant Psychotherapy in its tiered approach to parent-infant services.

Methods

A comprehensive search (electronic databases, reference lists, and contacting of study authors and other experts) was conducted for randomised controlled trials (RCT) and quasi-RCTs that:

- Compared PIP with a control treatment (waiting list, treatment as usual, or another treatment)

- Included parents with infants aged 24 months or less

- Used at least one standardised measure of parental or infant functioning

Meta-analyses were conducted for each of the primary outcomes (where data were available) and separately for PIP versus waiting list or treatment as usual and PIP versus another treatment. Results were reported as Relative Risk (RR) for dichotomous outcomes and Standardised Mean Difference (SMD) for continuous outcomes

Results

Eight studies including 846 participants were included, though smaller numbers were included for each of the separate primary outcomes as each study only reported on a subset of the primary outcomes of interest. The studies providing data for the meta-analysis were assessed by the authors as being of low or very low quality. For most of the primary outcomes there was no evidence of benefit of PIP over any of the control treatments.

- Parental depression Relative Risk (RR) 0.74 (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.04)

- Parent-child interaction (parental sensitivity) Standard Mean Difference (SMD) -0.13 (95% CI -0.64 to 0.38)

- Infant outcomes: attachment – secure attachment RR 8.93 (95% CI 1.25 to 63.70)

- Infant outcomes: externalising behaviour SMD 0.22 (95% CI -0.34 to 0.77)

There was a difference found for infant attachment status, but not other infant outcomes. Infants were more likely to be assessed as securely attached following PIP compared to control group.

PIP was only shown to be beneficial for infant attachment status, and even then the trials were assessed as low to very low quality.

Conclusions

The authors conclude that:

PIP is a promising model in terms of improving infant attachment security in high-risk families, there were no significant differences compared with no-treatment or treatment-as-usual for other parent-based or relationship-based outcomes, and no evidence that PIP is more effective than other methods of working with parents or infants.

Strengths and weaknesses

This is a well-conducted systematic review with clearly stated a priori outcomes of interest, as would be expected of a Cochrane review. The most significant weakness is the striking lack of high quality research evidence to support PIP as an effective intervention.

Comment

The key finding from this review is that the evidence for most of the a priori primary outcomes (child outcome, parental sensitivity, parental depression) shows no benefit of PIP. There is some evidence for a benefit on child attachment status when PIP is compared to no treatment, but the authors note that this finding is based on two studies which they rate as low or very low quality evidence. In addition the very wide confidence intervals (1.25 to 63.70) suggest the estimate of effect is not precise. There is no evidence of benefit of PIP over other treatment interventions (which included psychoeducational interventions and cognitive behaviour therapy).

There is no evidence of benefit of PIP over other treatment interventions.

Two key points struck me as I studied this review.

- First, there are relatively few studies, and these are reported as providing weak or very weak evidence (i.e. either having important methodological limitations or being reported in a way that does not rule these out). This is a significant problem, particularly given that parents in over 800 families have consented for themselves and their infants to take part in research which the authors of this review conclude is weak and doesn’t help much with the planning of healthcare. There are apparently other studies underway, and it is crucial that these are robustly conducted to a high standard and with sufficient power. There is no excuse for further small, poorly conducted and reported trials, particularly when the health of infants is at stake. It should go without saying that the highest standards of research are an ethical prerequisite.

- The second point is the contrast between the available evidence and the promotion of PIP as an “evidence-based treatment” for infant mental health problems. This mismatch strikes me as potentially problematic, particularly when there is evidence that other briefer treatments, such as ViPP, can be effective in improving outcomes such as sensitive parenting and infant attachment status. Parent Infant Psychotherapy (PIP) may have a role in the treatment of infant mental health problems and parenting difficulties, and future trials may help to elucidate that (the Cochrane review identifies 5 trials that are currently underway), but on the basis of the evidence in this Cochrane review, it’s role is far from clear.

Parent Infant Psychotherapy is being promoted as an “evidence-based treatment”, but this new review has found very little reliable evidence to support this view.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The Cochrane review (Barlow et al, 2015) was funded by PIP-UK (a “Charitable organisation with a remit to establish parent-infant psychotherapy services across England”).

Paul Ramchandani receives funding from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) to develop and evaluate early interventions to promote infant mental health in early life, including a randomised controlled trial of ViPP for children at risk of behavioural problems.

Links

Barlow J, Bennett C, Midgley N, Larkin SK, Wei Y. (2015) Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD010534. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010534.pub2.

Juffer F, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, and Van IJzendoorn MH. (Eds) (2007) Promoting positive parenting: An attachment-based intervention. New York: Routledge.

Groeneveld MG, Vermeer HJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Linting M. (2011) Enhancing home-based child care quality through video feedback intervention: randomized controlled trial. J Fam Psychol. 2011 Feb;25(1):86-96. doi: 10.1037/a0022451. [PubMed abstract]

Leadsom A, Field F, Barstow P, Lucas C. (2014) The 1001 Critical Days: The Importance of the Conception to Age Two Period. A cross-party manifesto (PDF). Wave Trust, 2014.

RT @Mental_Elf: Parent Infant Psychotherapy: a gap in the evidence http://t.co/bpshBbOdaR

“@Mental_Elf: Parent Infant Psychotherapy: gap in evidence http://t.co/yeljvUc0kC”

Not really !! All said so beautifully by DW Winnicott

The elves are v. excited today! We have a debut blog from @paulramchandani on Parent Infant Psychotherapy http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

Olivia Cialdi liked this on Facebook.

#ActuSanté – Parent Infant #Psychotherapy: a gap in the evidence http://t.co/WLa4rLJCEq By @paulramchandani via @Mental_Elf

Hi @DrG_NHS New #Cochrane review on Parent Infant Psychotherapy makes for interesting reading http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

Hi @mirandarwolpert @AFCevents @CAMHS_EBPU Welcome your comments on our Parent Infant Psychotherapy blog http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

Hi @EIFCOppenheim @TheEIFoundation Any comment on our Parent Infant Psychotherapy blog? http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

Morning @AIMH16 Any thoughts on our Parent Infant Psychotherapy blog? http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

@mental_elf @aimh16 Where are the data proving the opening “Many MH problems affecting adults have their roots in childhood & adolescence”?

@mental_elf @aimh16 For ex:No relationship b/n childhood trauma & psychosis per se in BPD( n=2019)

http://t.co/WjNDuKFUGi… via @soniajohnson

@mental_elf @aimh16 The enduring & pervasive Freudian legacy of blaming the parents hasn’t been proven by any good studies. Many have tried.

“no excuse for further small, poorly conducted&reported trials” as true for : Trauma & MI Cause” http://t.co/ziV2O2Y0DQ @mental_elf @aimh16

RT @Mental_Elf: New #Cochrane review finds no evidence of benefit of Parent Infant Psychotherapy over other treatments http://t.co/bpshBbwC…

What’s @YoungMindsUK view on Parent Infant Psychotherapy? http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

The @first1001days manifesto features Parent Infant Psychotherapy centre-stage, but where’s the evidence? http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

The Mental Elf liked this on Facebook.

Should Parent Infant Psychotherapy be promoted as an evidence-based treatment? New #CochraneEvidence suggests not http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj

@Mental_Elf quit psychotherapy and do reiki w hypnotherapy

Parent Infant Psychotherapy: a gap in the evidence http://t.co/LaMa2rC1uE via @sharethis

RT @KarenJBateson: Good blog by @Mental_Elf about PIP. Could be promising Rx but more high quality research clearly required. http://t.co/n…

RT @paulramchandani: my blog for @Mental_Elf on the new @cochranecollab systematic review of Parent infant psychotherapy

http://t.co/tJaV7D…

RT @Mental_Elf: Don’t miss – Parent Infant Psychotherapy: a gap in the evidence http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj #EBP

We are grateful to Professor Ramchandani for his very thoughtful review. One of the key issues for us in terms of the findings of this review is that despite the fact that we identified and included eight studies that met all of our inclusion criteria, there was considerable heterogeneity in terms of the comparisons made (e.g. control group versus a second intervention only) and the outcomes measured, thereby precluding us from meta-analysing most outcomes and with insufficient power for the few meta-analyses that were possible for us to be confident about the results. This points to an urgent need for further research to increase the power of this review to identify significant differences across groups.

The point raised by Professor Ramchandani about the existence of other briefer methods of intervening such as ViPP, is an important one. Parent-infant psychotherapy is relatively speaking, a fairly brief method of working, and many parent-infant psychotherapists now also use video-feedback. But most models of PIP also attempt to bring about change by increasing the parents awareness of unconscious motivations many of which originate with their own experiences of being parented; this gives parent-infant psychotherapy another route by which to bring about change, albeit one that may not be suited to the needs of all parents. Bakermans-Kranenburg (1998) comparing video feedback with interventions that included discussions of attachment found that the different forms of the therapy were differentially effective for parents with different types of attachment insecurity.

So, while it would ultimately be rather disappointing if these dyadic methods of working that explicitly target the parent-infant relationship really aren’t any better than CBT, it seems likely that in the long-term, interventions such as PIP and ViPP may well turn out to be differentially effective with parents who have different attachment, and other, needs. Both may ultimately therefore have a place in terms of increasing the attachment security of very high-risk groups of infants.

Cochrane find little evidence to support the claim that Parent Infant Psychotherapy is an evidence-based treatment http://t.co/bpshBbOdaR

@Mental_Elf but didn’t it help with attachments? That’s crucial if it does …

MT @Mental_Elf: Do you practise Parent Infant Psychotherapy? Read the latest #CochraneEvidence http://t.co/lB9OWsPKoK #PIP

@CochraneLibrary @Mental_Elf @Llevadores

@paulramchandani ‘s great new @Mental_Elf blog on evidence base of Parent Infant Psychotherapy.

http://t.co/a8HXFmIhR6

Parent infant psychotherapy – best evidence summary http://t.co/dLKzrWB9ik

RT @CochraneLibrary: MT @Mental_Elf: Do you practise Parent Infant Psychotherapy? Check latest #CochraneEvidence http://t.co/HyguD6rTkO #PIP

Parent Infant Psychotherapy, “promoted as an ‘evidence-based treatment'” But “very little” evidence to support this http://t.co/neohb6rYXv

Most popular blog this week? It’s @paulramchandani on the lack of evidence for Parent Infant Psychotherapy http://t.co/bpshBbwCjj